|

CAMPING

IN ICELAND 2017 - Iceland's capital

city Reykjavík including visit to the Alţing Parliament, Hveragerđi and

Hengill geothermal area, Nesjavellir, south coast at Stokkseyri, Eyrarbakki and Ţorlákshöfn, Ţingvellir, Geysir

spouting hot springs, Gullfoss waterfalls,

and Selfoss: CAMPING

IN ICELAND 2017 - Iceland's capital

city Reykjavík including visit to the Alţing Parliament, Hveragerđi and

Hengill geothermal area, Nesjavellir, south coast at Stokkseyri, Eyrarbakki and Ţorlákshöfn, Ţingvellir, Geysir

spouting hot springs, Gullfoss waterfalls,

and Selfoss:

Approaching the Reykjavík conurbation:

traffic on the Ring Road was intense as we

approached the outer suburb of Mosfellsbćr where we encountered the first speed

cameras seen in the whole of Iceland. Thankful for the sat-nav's reassuring

guidance, we threaded a way through Reykjavík's eastern suburbs on the first

stretch of dual carriageway seen so far in the country. Our recollections of Reykjavík

from 1972 were of a small town of wooden houses. Inevitably things had changed in 45

years, and the capital city now seemed no different from any other major

conurbation: an anonymous sprawl of concrete with commercial parks lining the

highway, aggressively speeding traffic, and a bewildering series of roundabouts

and intersections.

|

Click on 3 highlighted areas of

map

for details of

Reykjavík,

Ţingvellir,

Geysir and Gullfoss |

|

We branched off from Route 1 Ring Road onto the

Route 41 dual-carriageway (Click on Map 1 right) still amid busy city

traffic, and passed around the city towards the southern suburbs. The main

Reykjavík campsite, although close to the city centre, was notoriously

overcrowded and expensive, and instead we had chosen the better value and

hopefully more peaceful hostel-campsite in

the southern suburb of Hafnarfjörđur.

Our sat-nav guided us off the main Route 41 highway, which led out to Keflavík,

turning into a narrow residential street and eventually to the gates of

Hafnarfjörđur Hostel-Camping. the southern suburb of Hafnarfjörđur.

Our sat-nav guided us off the main Route 41 highway, which led out to Keflavík,

turning into a narrow residential street and eventually to the gates of

Hafnarfjörđur Hostel-Camping.

Hafnarfjörđur Hostel-Camping: still dazed from the city traffic, we were greeted at reception with a friendly

and helpful welcome; the lad even recalled our earlier phone enquiry. He gave us

city maps and details of bus times into Reykjavík, and the 10 minute walking

route to the bus stop. The hostel-campsite was run by the Scout Association,

and reception was well set up with all the information that visitors might

require. The charge was an all-inclusive 1,000kr/person, a worthwhile seniors'

reduction from the full price of 1,700kr. Electricity was a further 1,000kr, but

the small camping area fitted with power supplies was already full; the

adjoining open parkland (no power) was at this stage still almost empty. We

found a space down at the far end and settled in beneath a lava embankment,

looking across the public parkland towards a modern church up on a hill to where

the path to the bus stop led. The forecast still showed Monday and Wednesday as

the least wet days for visiting Reykjavík, although tomorrow was the Labour Day public holiday Monday

with a reduced bus service. The parkland camping area gradually filled up during

the evening with hire-cars/tents, and yet again we were woken by late arrivals

thoughtlessly slamming car doors.

Bus into Reykjavík: a bright, sunny start with the forecast

now showing no rain during the day. We were away early for our first day in the

capital city, and followed the path from the camping area up past the modern

church, through a school grounds and residential area to a main road, to wait at

the Hraunbrún bus stop (Photo 1 - Bus into Reykjavík)

(see above left).

Even with Sunday/holiday reduced service, the #1 buses into the city ran Bus into Reykjavík: a bright, sunny start with the forecast

now showing no rain during the day. We were away early for our first day in the

capital city, and followed the path from the camping area up past the modern

church, through a school grounds and residential area to a main road, to wait at

the Hraunbrún bus stop (Photo 1 - Bus into Reykjavík)

(see above left).

Even with Sunday/holiday reduced service, the #1 buses into the city ran every

30 minutes, and the 10-50am bus came along promptly. We had the 210kr coins

ready for our seniors' tickets, and followed the stops into the city centre on our Strćtó

(Icelandic bus network) map-print to get off at Lćkjargata bus

stop. At this time of day on a public holiday, the city was still remarkably

quiet. every

30 minutes, and the 10-50am bus came along promptly. We had the 210kr coins

ready for our seniors' tickets, and followed the stops into the city centre on our Strćtó

(Icelandic bus network) map-print to get off at Lćkjargata bus

stop. At this time of day on a public holiday, the city was still remarkably

quiet.

Tjörnin (City Lake),

Reykjavík Ráđhúsiđ (City Hall), and the Icelandic topographical model-map

Íslandslíkan: we walked around the northern side of Tjörnin (City

Lake) to find the

Reykjavík Ráđhúsiđ (City Hall), a classic steel and glass rectangular piece of

Nordic showpiece architecture set astride the city lake and opened in 1992 (see

above left) (Photo

2 - Reykjavík Ráđhúsiđ). The

main hall of the building overlooking the lake contained a magnificent

topographical display of Iceland, the Íslandslíkan: a 4 man team had taken 5

years to construct this detailed relief model-map of the country to a horizontal

scale of 1:50k and vertical scale doubled for emphasis. We spent a good half

hour studying this impressive model (see right)

(Photo

3 - Topographical relief model), following our route around the county and trying to

identify places and features. Five aspects were of immediate notice:

- the immense mountainous scale of the East and West

Fjords areas

- the huge areas still covered by ice-sheets

and glaciers, particularly Vatnajökull in the east

- the comparatively flat and barren volcanic central plateau

areas of the country

- the evident transverse line of the

tectonic boundary ridge running SW~NE across the width of the country,

dotted with isolated volcanic peaks and craters such as Askja

- the vast extent of sandurs (glacial

outwash plains) along the indented southern coastline

The startling

impression which the model gave of Iceland's severe terrain was a cautious alert to those considering driving around Iceland; even

the south coast where we were to travel next looked fearsome (see above right). The startling

impression which the model gave of Iceland's severe terrain was a cautious alert to those considering driving around Iceland; even

the south coast where we were to travel next looked fearsome (see above right).

We walked along the lake-side path of Tjörnin

taking photos in the pleasant morning sunshine, as local families fed the ducks

(see left) (Photo 4 - Feeding the ducks on Reykjavík's Tjörnin),

and sat on a bench to eat our lunch sandwiches

looking out across the lake towards the Hallgrímskirkja church on the opposite

city hillside

(see right). At the far end of the lake, the attractive old house of

Rađherrabústađurinn (Minister's House) (see below right), once wooden and now faced with more

weather-resistant corrugated material, provided further photographic opportunity

as did the view looking down the length of Tjörnin towards the Ráđhúsiđ (see

below left).

Reykjavík Old Town:

back along past the Ráđhúsiđ, we walked through to the small-sized dark basalt

building of the Alţingishúsiđ, Parliament House. The imposing front

façade,

inscribed with the date of construction The imposing front

façade,

inscribed with the date of construction 1881, was in deep shade at this time of

day, but around on the sunny south side, we entered the peaceful flower

gardens of the Alţing to photograph the building's rear façade

(Photo 5 - Alţing gardens). As part of the

trip's planning, we had exchanged emails with a member of the Alţing Secretariat

in an attempt to arrange a visit, and had been advised to make contact when we

arrived at Reykjavík; we were still hoping to arrange the visit for our second

day in the city on Wednesday.

1881, was in deep shade at this time of

day, but around on the sunny south side, we entered the peaceful flower

gardens of the Alţing to photograph the building's rear façade

(Photo 5 - Alţing gardens). As part of the

trip's planning, we had exchanged emails with a member of the Alţing Secretariat

in an attempt to arrange a visit, and had been advised to make contact when we

arrived at Reykjavík; we were still hoping to arrange the visit for our second

day in the city on Wednesday.

Round to Austurvöllur at the front of the

Alţing, this rather unassuming grassy parkland square has played an important

part in Reykjavík's historic past and in recent years of political and economic

turmoil. The square is said to be the site of the farm founded by Iceland's

first settler, Ingólfur Arnasson. Exiled from Norway for murdering the son of a

local earl in a blood feud, he sailed with his household and possessions for

Iceland around 870 AD, planning to settle there. In sight of land, Ingólfur

observed the Viking tradition of throwing overboard his wooden high seat

pillars, symbols of his chieftain's authority, vowing to settle wherever the

gods brought them ashore. It took 3 years for his slaves to find them, while

Ingólfur wintered along Iceland's south coast. According to the Icelandic Book

of Settlements (Landnámabók), the pillars were located in a SW bay, and

in 874 AD Ingólfur settled there, naming the place Reykjavík (meaning Smokey Bay)

after the steaming hot springs, and becoming Iceland's first permanent settler. Austurvöllur is traditionally viewed as the site of Ingólfur's farmstead, and the Icelandic Book

of Settlements (Landnámabók), the pillars were located in a SW bay, and

in 874 AD Ingólfur settled there, naming the place Reykjavík (meaning Smokey Bay)

after the steaming hot springs, and becoming Iceland's first permanent settler. Austurvöllur is traditionally viewed as the site of Ingólfur's farmstead, and

now in the centre of the square a statue of Jón Sigurđsson, the 19th century

political agitator for Icelandic independence, entitled Pride of Iceland, its

Sword and Shields, stands facing the Alţing. now in the centre of the square a statue of Jón Sigurđsson, the 19th century

political agitator for Icelandic independence, entitled Pride of Iceland, its

Sword and Shields, stands facing the Alţing.

Along Kirkjustrćti, we reached Ađalstrćti, Reykjavík's oldest street said to be

the route taken by Ingólfur from his farmstead down to the sea. It is now a

rather nondescript street of restaurants occupying the old buildings; the oldest

of these at number 10, a wooden structure, was once a weaving shed and

also the home of Skúli Magnússon (1711~94) (see left), the 18th century High Sheriff of Iceland who

began Reykjavík's rise to become in time the capital by importing foreign

machinery to establish craft industries, opening mills and tanneries. The

broad-shouldered statue of Skúli Magnússon, the man regarded as the city's founding

father, stood at the

end of Ađalstrćti (see right). At the far end, we reached the corner of Hafnartrćti (Harbour

Street), so called since this land once bordered the sea, giving access to the

harbour. During the time of the 1602~1855 Trade Monopoly, wealthy Danish

merchants established their warehouses here, making it the centre of the city's

commercial life. Today Hafnartrćti is several blocks inland from the modern

harbour which has been extended outwards on reclaimed land, and along with

neighbouring Austurstrćti and Tryggvagata, is now coining in the tourist income,

filled with grubby-looking bars and restaurants.

Reykjavík's Old Harbour and Harpa Opera House: Geirsgata led

us along to Reykjavík's Old Harbour area, which had been extended out on

reclaimed land in 1913~15; before this, larger vessels had to be moored out in

the bay and goods ferried in and out on smaller boats. Today there were still

shipyards repairing vessels up on stocks (see left), with piers now filled with small

fishing boats along with whale- and puffin-watching boats aimed at the tourist trade.

Ironically at a pier opposite the whale-watching boats, 2 whaling ships named

Hvalur 8 and 9 were moored (see right), identified by the H (for Hval) on

their funnels (Photo

6 - Whaling ships), although it did not look as if they had been to sea for a while.

Just along the quay however, a monstrous Danish cruise-ship polluted both the

visual skyline of the port and the clean sea air with its diesel fumes. We

ambled around to the far of the quays where behind securely locked security

gates, a large Icelandic coast-guard vessel was moored (see below left) (Photo

7 - Reykjavík Old Harbour); we wondered if this had

played any part in the Cod Wars, harassing British trawlers and severing trawl

lines! The quay-side path led around to the controversial Harpa Concert

Hall and Opera House. This huge, angular glass building was half-constructed in

2008 at the time of Iceland's economic crash, and at such a time of financial

hardship, politicians had demanded the scheme should be scrapped. The building

however went ahead, Reykjavík's Old Harbour and Harpa Opera House: Geirsgata led

us along to Reykjavík's Old Harbour area, which had been extended out on

reclaimed land in 1913~15; before this, larger vessels had to be moored out in

the bay and goods ferried in and out on smaller boats. Today there were still

shipyards repairing vessels up on stocks (see left), with piers now filled with small

fishing boats along with whale- and puffin-watching boats aimed at the tourist trade.

Ironically at a pier opposite the whale-watching boats, 2 whaling ships named

Hvalur 8 and 9 were moored (see right), identified by the H (for Hval) on

their funnels (Photo

6 - Whaling ships), although it did not look as if they had been to sea for a while.

Just along the quay however, a monstrous Danish cruise-ship polluted both the

visual skyline of the port and the clean sea air with its diesel fumes. We

ambled around to the far of the quays where behind securely locked security

gates, a large Icelandic coast-guard vessel was moored (see below left) (Photo

7 - Reykjavík Old Harbour); we wondered if this had

played any part in the Cod Wars, harassing British trawlers and severing trawl

lines! The quay-side path led around to the controversial Harpa Concert

Hall and Opera House. This huge, angular glass building was half-constructed in

2008 at the time of Iceland's economic crash, and at such a time of financial

hardship, politicians had demanded the scheme should be scrapped. The building

however went ahead,

producing much derision and contention, and now dominates

the harbour sky-line (Photo

8 - Harpa Concert Hall). Now home to the producing much derision and contention, and now dominates

the harbour sky-line (Photo

8 - Harpa Concert Hall). Now home to the Icelandic Symphony Orchestra and National

Opera, Harpa should (according to our guide books) have been free entry

for visitors to amble around the spacious interior. But of course, in today's greed-driven, tourist

orientated Reykjavík, nothing comes for nothing any more: with everyone on the

make, the answer from an attendant was yes we could walk around, but only if we

paid an arm and a leg to join a guided tour. We wouldn't and we didn't! And

contented ourselves with photographs of the hexagonal panes of glass and the

reflective interior (see right). Icelandic Symphony Orchestra and National

Opera, Harpa should (according to our guide books) have been free entry

for visitors to amble around the spacious interior. But of course, in today's greed-driven, tourist

orientated Reykjavík, nothing comes for nothing any more: with everyone on the

make, the answer from an attendant was yes we could walk around, but only if we

paid an arm and a leg to join a guided tour. We wouldn't and we didn't! And

contented ourselves with photographs of the hexagonal panes of glass and the

reflective interior (see right).

Hallgrímskirkja hill-top church: from here

we edged a way through and around an enormous construction site for a new

underpass, which sullied this area of the city, and climbed the grassy hillock

topped by the statue of Ingólfur Arnasson. Strolling on, across to Lćkjartorg,

we waded through the tourist hordes now filling unimpressive Austurtrćti (see

below left) and

back along the equally uninteresting Hafnartrćti. With the old part of Reykjavík

being so bijou, we had covered our planned ground, and with it still being only

3-30pm, we set off up Bankatrćti and Skólavörđustígur to visit the Hallgrímskirkja

church (see below right), whose white concrete 73m high tower dominates the city sky-line from

its

commanding hill-top position

(Photo 9 - Hallgrímskirkja Church). The Hallgrímskirkja is the most renowned work of

the Icelandic State Architect Guđjón Samúelsson, who also designed its

commanding hill-top position

(Photo 9 - Hallgrímskirkja Church). The Hallgrímskirkja is the most renowned work of

the Icelandic State Architect Guđjón Samúelsson, who also designed Akureyri

Church and Ísafjörđur Culture House. The design was finalised in 1937 but work

only got underway after WW2 in 1945. Constructed from reinforced concrete, the

church was only completed and consecrated in 1986, as part of the City's

bicentennial celebrations. The slow rate of progress was due to the work being

carried out by a small family firm of one man and his son! Hallgrímskirkja is

dedicated to the 17th century Icelandic writer of passion hymns, Hallgrímur

Pétursson. The forecourt fronting the church is guarded over by an almost

comical statue of Leifur

Eiríksson (see below left), donated by the USA in 1930 on the occasion of the Icelandic

Parliament's millennium celebrations. The bare white lines of the church's

interior emphasised its peaceful Gothic height. Closer examination of the finish

suggested that the rough faced concrete lining was sprayed onto the structural

support elements. The west end was dominated by the church's huge concert organ

15m in height. Tourist numbers had been tolerable during earlier part of the

day, but as we had climbed the hill, hordes of the most gormless tourist

specimens milled everywhere, and now Hallgrímskirkja's plain chancel's solemnity

was sullied by crowd's of mindless tourists abusing the peaceful setting for

their ludicrous selfies. Akureyri

Church and Ísafjörđur Culture House. The design was finalised in 1937 but work

only got underway after WW2 in 1945. Constructed from reinforced concrete, the

church was only completed and consecrated in 1986, as part of the City's

bicentennial celebrations. The slow rate of progress was due to the work being

carried out by a small family firm of one man and his son! Hallgrímskirkja is

dedicated to the 17th century Icelandic writer of passion hymns, Hallgrímur

Pétursson. The forecourt fronting the church is guarded over by an almost

comical statue of Leifur

Eiríksson (see below left), donated by the USA in 1930 on the occasion of the Icelandic

Parliament's millennium celebrations. The bare white lines of the church's

interior emphasised its peaceful Gothic height. Closer examination of the finish

suggested that the rough faced concrete lining was sprayed onto the structural

support elements. The west end was dominated by the church's huge concert organ

15m in height. Tourist numbers had been tolerable during earlier part of the

day, but as we had climbed the hill, hordes of the most gormless tourist

specimens milled everywhere, and now Hallgrímskirkja's plain chancel's solemnity

was sullied by crowd's of mindless tourists abusing the peaceful setting for

their ludicrous selfies.

Return to camp at

Hafnarfjörđur: leaving the hordes behind, we ambled down Njarđargata

and Laufásvegur to Tjörnin, and headed back towards the Alţing, hoping that the

sun might have worked its way around to light the front façade. But no, and with

the time now gone 5-00pm we found a bus stop in Vonarstrćti by the Return to camp at

Hafnarfjörđur: leaving the hordes behind, we ambled down Njarđargata

and Laufásvegur to Tjörnin, and headed back towards the Alţing, hoping that the

sun might have worked its way around to light the front façade. But no, and with

the time now gone 5-00pm we found a bus stop in Vonarstrćti by the Ráđhúsiđ for

our return #1 bus to the campsite at

Hafnarfjörđur (see left). It had been a highly successful first day. Reykjavík is certainly

not a startling capital city: it had mushroomed in size from the scattering of

wooden buildings recalled from 1972, but the old centre was still sufficiently

compact that you could walk from one side to the other in 20 minutes. But like

the country as a whole, the capital city was in danger of being utterly

overwhelmed by the mindless hordes of tourists now flooding here the whole year

round. But just looking around at these folk, you really are left wondering why

them come, so evidently incurious and indifferent to all they are seeing, and so

readily relieved of their money! Reykjavík could never be described as an

attractive city, and there is only so far that the contrived image of the

Vikings can be exploited by their modern day equivalents now universally on the

make to milk the tourist boom for a quick buck before the bubble bursts. Ráđhúsiđ for

our return #1 bus to the campsite at

Hafnarfjörđur (see left). It had been a highly successful first day. Reykjavík is certainly

not a startling capital city: it had mushroomed in size from the scattering of

wooden buildings recalled from 1972, but the old centre was still sufficiently

compact that you could walk from one side to the other in 20 minutes. But like

the country as a whole, the capital city was in danger of being utterly

overwhelmed by the mindless hordes of tourists now flooding here the whole year

round. But just looking around at these folk, you really are left wondering why

them come, so evidently incurious and indifferent to all they are seeing, and so

readily relieved of their money! Reykjavík could never be described as an

attractive city, and there is only so far that the contrived image of the

Vikings can be exploited by their modern day equivalents now universally on the

make to milk the tourist boom for a quick buck before the bubble bursts.

A cold, wet day in camp at

Hafnarfjörđur:

with rain forecast for the following day (our 47th wedding anniversary as it

happened), we should spend the day in camp and make full use of the

campsite's free washing machine. Before beginning a day's work this morning, we

telephoned the Alţing in an attempt to arrange a visit. The official we had

exchanged pre-trip emails with was on holiday, but to our amazement, a colleague

agreed to show us the Alţing at 12 noon tomorrow. Our visit to the Icelandic

Parliament was on. Today's rain was forecast to begin at 12-00, so late morning

we worked out a walking route to a Netto supermarket said to be in the nearby

housing estate. Sure enough the path led from the campsite up into the

residential area of apartment blocks and ticky-tacky pre-fabs, but this path had

a uniquely Icelandic tone to it, passing through a so late morning

we worked out a walking route to a Netto supermarket said to be in the nearby

housing estate. Sure enough the path led from the campsite up into the

residential area of apartment blocks and ticky-tacky pre-fabs, but this path had

a uniquely Icelandic tone to it, passing through a

lava field which conveniently

had spread among the houses and a children's playground! We completed our provisions

shopping and returned for lunch in camp, and an afternoon of work. The rain

began as forecast at lunchtime, drizzle at first then more determined rain, with

a bitterly chill northern wind blowing. With no power for heating, George's

inside temperature dropped lower and lower reaching 12şC. As the rain

intensified and continued all afternoon, we piled on multi-layered Arctic gear

for warmth, and that night with heavy cloud cover, it was unaccustomedly dark. lava field which conveniently

had spread among the houses and a children's playground! We completed our provisions

shopping and returned for lunch in camp, and an afternoon of work. The rain

began as forecast at lunchtime, drizzle at first then more determined rain, with

a bitterly chill northern wind blowing. With no power for heating, George's

inside temperature dropped lower and lower reaching 12şC. As the rain

intensified and continued all afternoon, we piled on multi-layered Arctic gear

for warmth, and that night with heavy cloud cover, it was unaccustomedly dark.

Our visit to the Alţing, the Icelandic

Parliament:

the rain had stopped overnight, but this morning the sky was still heavily

overcast and air chill. We again walked up for the 10-50am bus from Hraunbrun,

and followed the now familiar stops into the city centre. We had a half hour

before our appointment at the Alţing, time to admire the statue of Iceland's

early 20th century Home Rule Prime Minister Hannes Hafstein outside Government

House in Lćkjargata (see above right), which now houses the current Prime Minister's offices. We walked

through to Austurvöllur for photos of Jón Sigurđsson's statue, before reporting

to the Alţing for our visit (see left) (Photo

10 - Alţing - Icelandic Parliament).

The Alţing, claimed by Icelanders as one of the

world's oldest extant parliamentary institutions, first met in 930 AD as a

general assembly (thing) of the Icelandic Commonwealth, when the country's most

powerful clan chieftains (Gođar), along with all Icelandic free men,

gathered on the plains at Ţingvellir once a year to discuss issues, decide on

legislation, dispense justice, and resolve disputes. The centre of the gathering

was the Lögberg (Law Rock) from which the Lawspeaker recited the Laws and presided over the Assembly. When the Icelanders submitted to the authority of

the Norwegian monarchy in 1262 under the terms of the Old Covenant, the

supremacy of the Alţing was diminished, as executive power was now vested with

the King and his officials. The role of the Alţing became more judicial as a

national court after the crowns of Norway and Denmark merged and the Danish

king's rule became absolute. The Alţing was disbanded in 1800, but a royal

decree re-established it as a consultative body for the crown in 1843; from then

it became increasingly a forum for the Icelanders' long struggle for

independence f The Alţing, claimed by Icelanders as one of the

world's oldest extant parliamentary institutions, first met in 930 AD as a

general assembly (thing) of the Icelandic Commonwealth, when the country's most

powerful clan chieftains (Gođar), along with all Icelandic free men,

gathered on the plains at Ţingvellir once a year to discuss issues, decide on

legislation, dispense justice, and resolve disputes. The centre of the gathering

was the Lögberg (Law Rock) from which the Lawspeaker recited the Laws and presided over the Assembly. When the Icelanders submitted to the authority of

the Norwegian monarchy in 1262 under the terms of the Old Covenant, the

supremacy of the Alţing was diminished, as executive power was now vested with

the King and his officials. The role of the Alţing became more judicial as a

national court after the crowns of Norway and Denmark merged and the Danish

king's rule became absolute. The Alţing was disbanded in 1800, but a royal

decree re-established it as a consultative body for the crown in 1843; from then

it became increasingly a forum for the Icelanders' long struggle for

independence f rom Danish rule, led by the independence reformer Jón Sigurđsson

until his death in 1879. The Constitution granted to Iceland by Danish King Christian

IX in 1874 granted the Alţing legislative powers in domestic matters. Iceland

achieved Home Rule in 1904 with Hannes Hafstein as the first Prime Minister, and

became a sovereign state in a monarchical union with Denmark in 1918. Iceland

finally became a fully independent republic on 17 June 1944 (Jón Sigurđsson's

birthday and now Icelandic Independent Day), with the Alţing assuming full

legislative powers along with the Icelandic President. rom Danish rule, led by the independence reformer Jón Sigurđsson

until his death in 1879. The Constitution granted to Iceland by Danish King Christian

IX in 1874 granted the Alţing legislative powers in domestic matters. Iceland

achieved Home Rule in 1904 with Hannes Hafstein as the first Prime Minister, and

became a sovereign state in a monarchical union with Denmark in 1918. Iceland

finally became a fully independent republic on 17 June 1944 (Jón Sigurđsson's

birthday and now Icelandic Independent Day), with the Alţing assuming full

legislative powers along with the Icelandic President.

The lady official we had spoken with on the

telephone yesterday greeted us at the Alţing reception, and we began our tour of

the Parliament, discussing constitutional issues as we went. The modern day Alţing

is composed of 63 Members, elected by proportional representation from the

country's 6 constituencies for a period of 4 years. Turnout in general elections

is usually around 80%. In the October 2016 election 7 parties took seats, but

with no party having an overall majority a period of political wrangling

followed; this resulted in a new coalition government being formed in January

2017, led by the Independence Party (21 seats) with Reform Party (7 seats) and

Bright Future Party (4 seats), controlling in total 32 seats. The Opposition

parties were: Left-Green Movement (10 seats), Pirate Party (10 seats),

Progressive Party (8 seats) and Social Democratic Alliance (3 seats), totalling

31 seats. The Independence Party leader Bjarni Benediktsson was appointed Prime

Minister. Of the 63 then serving MPs, 30 were women and 33 men. At its first

meeting of the new Parliament, the Alţing elects its Speaker from among its

members, and the lady-Speaker at the time of our visit was

Unnur Brá Konráđsdóttir. [Since our visit to Iceland, and following collapse of

the coalition government in September 2017, a further parliamentary snap

election in October resulted in a new coalition government being formed in

October 2017 led by Prime Minister Katrín

Jakobsdóttir of the Left-Green Movement who is still in office.] elected by proportional representation from the

country's 6 constituencies for a period of 4 years. Turnout in general elections

is usually around 80%. In the October 2016 election 7 parties took seats, but

with no party having an overall majority a period of political wrangling

followed; this resulted in a new coalition government being formed in January

2017, led by the Independence Party (21 seats) with Reform Party (7 seats) and

Bright Future Party (4 seats), controlling in total 32 seats. The Opposition

parties were: Left-Green Movement (10 seats), Pirate Party (10 seats),

Progressive Party (8 seats) and Social Democratic Alliance (3 seats), totalling

31 seats. The Independence Party leader Bjarni Benediktsson was appointed Prime

Minister. Of the 63 then serving MPs, 30 were women and 33 men. At its first

meeting of the new Parliament, the Alţing elects its Speaker from among its

members, and the lady-Speaker at the time of our visit was

Unnur Brá Konráđsdóttir. [Since our visit to Iceland, and following collapse of

the coalition government in September 2017, a further parliamentary snap

election in October resulted in a new coalition government being formed in

October 2017 led by Prime Minister Katrín

Jakobsdóttir of the Left-Green Movement who is still in office.]

From the public gallery of the Alţing, we could

look down into the traditionally laid out Parliamentary chamber (Photo

11 - Alţing plenary chamber) (see above right). Members are

seated, not in party groupings, but places are assigned randomly at the first

session of the year by drawing of lots. Ministers sit along the front of the

chamber,

and members address the Parliament from the podium. The From the public gallery of the Alţing, we could

look down into the traditionally laid out Parliamentary chamber (Photo

11 - Alţing plenary chamber) (see above right). Members are

seated, not in party groupings, but places are assigned randomly at the first

session of the year by drawing of lots. Ministers sit along the front of the

chamber,

and members address the Parliament from the podium. The only concession

to modernity is the electronic voting system from each seat with results

displayed on monitors The Alţing changed from bicameral to unicameral only in

1991. As we walked around, we discussed current issues such as attitude to

accession to EU membership; a national referendum is still to be called, but

public concerns are about protection of fishing rights around Iceland from

continental competition and agricultural imports. We had been very fortunate to

have been able to arrange the visit despite most of the staff being on holiday

during the summer recess, and we had secured our photos of the Alţing

Parliamentary chamber. only concession

to modernity is the electronic voting system from each seat with results

displayed on monitors The Alţing changed from bicameral to unicameral only in

1991. As we walked around, we discussed current issues such as attitude to

accession to EU membership; a national referendum is still to be called, but

public concerns are about protection of fishing rights around Iceland from

continental competition and agricultural imports. We had been very fortunate to

have been able to arrange the visit despite most of the staff being on holiday

during the summer recess, and we had secured our photos of the Alţing

Parliamentary chamber.

Reykjavík's Cathedral, the Domkirkjan:

we walked round to Reykjavík's Cathedral, the Neoclassical Domkirkjan (see above left)

which was now open for us to see the galleried plain Lutheran interior (see

right). The

church was built in 1796 after Danish King Christian VII abolished the 2 former

Catholic bishoprics of Hólar and Skálholt and established the Lutheran bishopric

of Reykjavík. The small  cathedral is the venue for the pre-Parliamentary new

session's service followed by procession along to the Alţing, although larger

state ceremonial services are held up at the larger Hallgrímskirkja. We tried

lunching again on the bench looking across Tjörnin, but today with the heavily

overcast sky and drizzly rain beginning, it was less memorable than in Monday's

sunshine. cathedral is the venue for the pre-Parliamentary new

session's service followed by procession along to the Alţing, although larger

state ceremonial services are held up at the larger Hallgrímskirkja. We tried

lunching again on the bench looking across Tjörnin, but today with the heavily

overcast sky and drizzly rain beginning, it was less memorable than in Monday's

sunshine.

National Museum of Iceland, Ţóđminjasafn Íslands:

Tjarnargata took us alongside Tjörnin and up to the Icelandic National

Museum of Iceland (Ţóđminjasafn Íslands), where a seniors' reduction combined

ticket of 1000kr gave entry here and the Culture House. The Museum's displays of

archaeological finds, artefacts, memorabilia and documents give a comprehensive

history of Iceland's development from its earliest settlement through to the

declaration of the Republic in 1944 and the present day. National Museum of Iceland, Ţóđminjasafn Íslands:

Tjarnargata took us alongside Tjörnin and up to the Icelandic National

Museum of Iceland (Ţóđminjasafn Íslands), where a seniors' reduction combined

ticket of 1000kr gave entry here and the Culture House. The Museum's displays of

archaeological finds, artefacts, memorabilia and documents give a comprehensive

history of Iceland's development from its earliest settlement through to the

declaration of the Republic in 1944 and the present day.

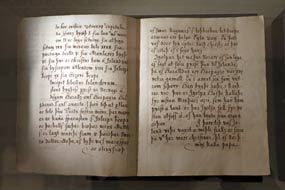

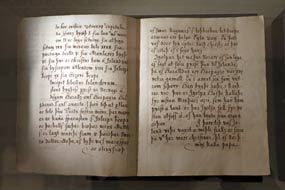

The displays from the period of Settlement, the

Commonwealth and Medieval period (800~1600 AD) were for us the most interesting:

a tiny bronze figurine of the pagan god Ţor (see left), artefacts from the earliest farming, the spinning

and weaving of woollen homespun, and the conversion to Christianity; the

devastating eruption of Hekla in the 12th century, and arrival of the Black

Death plague in the 14th century, the union with the Norwegian crown under the

1262 Old Covenant, the rise of foreign trade exports as farm and fish

production increased; the advent of writing of the Sagas illustrated by a

1681 manuscript of the Íslendingabók (see right), recording the lineage

of the founding Icelandic settlers, compiled originally by Ari the Wise in 1130

AD; displays illustrated the power, influence

and art of the Catholic Church, exemplified by the wonderfully ornate carved

wooden church doors from Valţjófsstađir in Ţórsmörk dating from ca 1200AD

(see right) depicting the Medieval tale of Le Chevalier au Lion, which had been whisked off

to Copenhagen by the Danes and only returned along

with Medieval manuscripts in

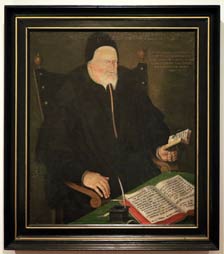

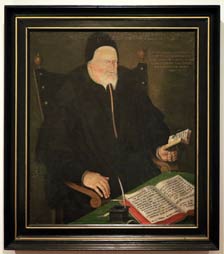

1930; exhibits illustrating society under Danish rule and the Reformation, with a

copy of Guđbrandur Ţorláksson's 1584 translation of the

Bible into Icelandic (Photo

12 - Guđbrandur's Bible) displayed

along with portraits of the literary Bishop of Hólar (see left) (See

log of our visit to Hólar). with Medieval manuscripts in

1930; exhibits illustrating society under Danish rule and the Reformation, with a

copy of Guđbrandur Ţorláksson's 1584 translation of the

Bible into Icelandic (Photo

12 - Guđbrandur's Bible) displayed

along with portraits of the literary Bishop of Hólar (see left) (See

log of our visit to Hólar).

The second set of displays on the 3rd floor

traced the history of Danish absolute rule from 1600~1800, the emerging

sense of Icelandic identity and demands for independence during the 19th

century, the development of industry and urbanisation during the 20th century

leading to the 1944 independent Republic; the concluding display on a circular

conveyer belt showed familiar consumer items from the 1970~80s, including a 'luggable'

PC similar to the one we had once used. The National Museum certainly showed a

worthwhile set of exhibits, the only criticism being the over-protective,

over-subdued lighting which made it almost impossible to see many of the items

or read the commentaries.

The Culture House

(Safnahúsiđ) and disappointing

lack of Saga manuscript displays:

it was by now gone 3-30pm, and we wanted to see the displays of Medieval Saga

manuscripts at the Culture House on the opposite side of the centre which closed

at 5-00pm. We therefore hot-footed it back past Tjörnin and along Lćkjargata to

reach the Culture House. Our guide book described this as having the country's

largest exhibition of Medieval manuscripts, including the Flateyjarbók

which was only returned by the Danish in 1971. When we presented our combined

tickets and asked about the Saga manuscripts, we were met with blank looks: no

Flateyjarbók with its Saga of the Greenlanders, which relates Leifur

Eiríksson's settlement in Vinland, and no Íslendingabók recording the

history of the Settlement. Most of the museum was given over to displays of

trivial contemporary ephemera passing as artwork, with just one dimly lit room displaying 6 copies

of the

Jónsbók

legal code but total absence of labelling or commentaries;

interesting, but not what we had been expecting. We took a cursory look, and

departed, making clear our evident irritation and disappointment. The next door

building in Hverfisgata was said to be Reykjavík's National Theatre, another of

State Architect Guđjón Samúelsson's designs, but it looked more legal code but total absence of labelling or commentaries;

interesting, but not what we had been expecting. We took a cursory look, and

departed, making clear our evident irritation and disappointment. The next door

building in Hverfisgata was said to be Reykjavík's National Theatre, another of

State Architect Guđjón Samúelsson's designs, but it looked more like a rather

care-worn 1950s version of a Gaumont Cinema and equally unimpressive! like a rather

care-worn 1950s version of a Gaumont Cinema and equally unimpressive!

Höfđi, venue of Regan and Gorbachev summit

meeting in 1986: it was by now

4-30pm, and we had time to walk along the sweeping waterfront passing with

scornful indifference a bunch of tourists busily snapping their selfies by

the Sólfar so-called 'attraction', meant to represent the skeletal outline of a

Viking ship; it was in truth more like a heap of twisted scrap metal, but it

served to detain the bevy of easily entertained tourists. With late afternoon

traffic on Sćbraut very busy, we continued around the shore-side path,

eventually finding the lone white house built in 1909 in Art Nouveau Jugenstil,

standing in a lawned area looking out across the bay towards the city (see above

left). This was Höfđi, built originally for the French consul, but now most noted as the venue

for the summit meeting of Regan and Gorbachev in 1986 (see right) which led to the

concluding of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty signed in 1991, and resulted

ultimately in the ending of the Cold War; a notable achievement in world history

now in process of being unravelled by their utterly unworthy successors Trump and Putin. We

just had time to take our photos of the house before a gaggle of Japanese

tourists overran the lawns.

Reykjavík University and the Nordic House (Norrćna húsiđ): we walked

through the back streets to find Hlemmur bus station, the terminus for our #1

bus; it was still only 5-30pm, and if we could break our journey back to

Hafnarfjörđur to stop off en route at the National Museum, we could see

Reykjavík University and the Nordic House. The bus driver duly issued us with

new tickets stamped valid until 7-00pm, and we took the bus back through the

centre to the Háskóli Íslands stop. Just around the corner, we reached the

grandiose main building of Reykjavík University (see left), yet another of State Architect Guđjón Samúelsson's

designs, opened in 1940 and fronted by large semi-circular lawns with views

across the city of the distant hill-top Reykjavík University and the Nordic House (Norrćna húsiđ): we walked

through the back streets to find Hlemmur bus station, the terminus for our #1

bus; it was still only 5-30pm, and if we could break our journey back to

Hafnarfjörđur to stop off en route at the National Museum, we could see

Reykjavík University and the Nordic House. The bus driver duly issued us with

new tickets stamped valid until 7-00pm, and we took the bus back through the

centre to the Háskóli Íslands stop. Just around the corner, we reached the

grandiose main building of Reykjavík University (see left), yet another of State Architect Guđjón Samúelsson's

designs, opened in 1940 and fronted by large semi-circular lawns with views

across the city of the distant hill-top Hallgrímskirkja church dominating

Reykjavík's sky-line (Photo

13 - Hallgrímskirkja church). The University

had opened originally in 1911 with just 45 students; today this number has

increased to 14,000. Hallgrímskirkja church dominating

Reykjavík's sky-line (Photo

13 - Hallgrímskirkja church). The University

had opened originally in 1911 with just 45 students; today this number has

increased to 14,000.

From the front of the University we could also

see a low and insignificant single storey building rather over-dominated

by its large slopping roof; this was the Norrćna húsiđ (Nordic House), one of

the modernist Finnish Architect Alvar Aalto's later designs from 1968 (see

right) (Photo

14 - Nordic House), and as

uninspiring as the rest of his work which we had seen all around Finland (Alvar Aalto's architectural designs).

The Norrćna húsiđ is a centre for Nordic culture in Reykjavík operated by the

Nordic Council of Ministers, to promote the art and literature of the

Nordic group of countries, and we walked over to talk a look around. Back

through the University grounds, we caught our #1 bus back out to Hafnarfjörđur,

and it was gone 7-30 by the time we were back at the campsite. We had enjoyed 2

fulsome and rewarding days in the capital, and tomorrow we begin the next phase

of the trip along Iceland's south coast beginning at Hveragerđi.

Bessastađir, the Icelandic Presidential

official residence:

for a city campsite, Hafnarfjörđur had served us well. Although lacking in power

supplies, the campsite was not unduly crowded; with

well-equipped facilities, it was reasonable value and we rated it at +4. Having re-stocked with provisions

at the Bessastađir, the Icelandic Presidential

official residence:

for a city campsite, Hafnarfjörđur had served us well. Although lacking in power

supplies, the campsite was not unduly crowded; with

well-equipped facilities, it was reasonable value and we rated it at +4. Having re-stocked with provisions

at the nearby Netto, we set course for Bessastađir just 5kms away on the

Álftanes peninsula. This peaceful former farmstead with its neighbouring

church, set on an isolated, wind-swept hillock surrounded by lava fields and

water, is now the official residence of the Icelandic President. Reflecting

Iceland's egalitarian political lack of pomp and ceremony, the lone house,

white-painted with red roof, although stately showed not a trace of ostentation

(see left) (Photo

15 - Bessastađir).

Apart from the house's immediate surrounds being off-limits, the only evidence

of security was a lone, empty police car parked alongside. There had been a farm

and church here at Bessastađir since the time of Settlement (see right). Snorri Sturlesson, when

Lawspeaker, purchased the farm in addition to his other land-holdings at Rekholt.

After his assassination, the Norwegian crown claimed the property, and the house

became the residence of the Royal Governor. The present house was completed in

1766, and was bought by a Reykjavík businessman in 1941 and donated to the State

to be used as the new Republic's Presidential residence. Rather hesitantly,

we walked across the lawns past the church for photos of Bessastađir, and for

the very first time in the whole of Iceland, we were able to enjoy the peace of

the setting with not a soul in sight other than a lone man mowing the lawns. nearby Netto, we set course for Bessastađir just 5kms away on the

Álftanes peninsula. This peaceful former farmstead with its neighbouring

church, set on an isolated, wind-swept hillock surrounded by lava fields and

water, is now the official residence of the Icelandic President. Reflecting

Iceland's egalitarian political lack of pomp and ceremony, the lone house,

white-painted with red roof, although stately showed not a trace of ostentation

(see left) (Photo

15 - Bessastađir).

Apart from the house's immediate surrounds being off-limits, the only evidence

of security was a lone, empty police car parked alongside. There had been a farm

and church here at Bessastađir since the time of Settlement (see right). Snorri Sturlesson, when

Lawspeaker, purchased the farm in addition to his other land-holdings at Rekholt.

After his assassination, the Norwegian crown claimed the property, and the house

became the residence of the Royal Governor. The present house was completed in

1766, and was bought by a Reykjavík businessman in 1941 and donated to the State

to be used as the new Republic's Presidential residence. Rather hesitantly,

we walked across the lawns past the church for photos of Bessastađir, and for

the very first time in the whole of Iceland, we were able to enjoy the peace of

the setting with not a soul in sight other than a lone man mowing the lawns.

Hellisheiđi geothermal power plant, and

dubious claims about 'clean' geothermal power: we now set course for

the exhibition centre at Hellisheiđi geothermal

generating plant just off Route 1 on the way towards Hveragerđi (click

here for detailed map of route), and drove back across the lava field

towards the Reykjavík conurbation. Traffic was reasonably light as we circled the city to re-join Route 1 eastwards. Paul happened to notice that

George's temperature gauge was not rising, and uncertain what was wrong, we

drove on for Hellisheiđi geothermal power plant, and

dubious claims about 'clean' geothermal power: we now set course for

the exhibition centre at Hellisheiđi geothermal

generating plant just off Route 1 on the way towards Hveragerđi (click

here for detailed map of route), and drove back across the lava field

towards the Reykjavík conurbation. Traffic was reasonably light as we circled the city to re-join Route 1 eastwards. Paul happened to notice that

George's temperature gauge was not rising, and uncertain what was wrong, we

drove on for now; the raised temperature warning light was not showing which

suggested it was either a failed gauge or more likely a faulty sensor. We made

steady progress on the Route 1 dual-carriageway across the moss-covered lava

fields of Svinahraun with its backdrop of volcanic mountains, to turn off to the Hellisheiđi

geothermal power plant (see left). At the parking area, we checked that George's coolant

level was up to the full mark, and managed to locate a VW agent in Reykjavík; an

appointment was made for Friday afternoon to check the temperature sensor. now; the raised temperature warning light was not showing which

suggested it was either a failed gauge or more likely a faulty sensor. We made

steady progress on the Route 1 dual-carriageway across the moss-covered lava

fields of Svinahraun with its backdrop of volcanic mountains, to turn off to the Hellisheiđi

geothermal power plant (see left). At the parking area, we checked that George's coolant

level was up to the full mark, and managed to locate a VW agent in Reykjavík; an

appointment was made for Friday afternoon to check the temperature sensor.

Hellisheiđi is Iceland's largest geothermal

electricity generating plant, and as a by-product it supplies all the domestic

hot water for Reykjavík whose storage tanks we had seen on the hill-top above

the city. Rain and ground water percolates down into surface rocks and is

heated by magma intrusions in the earth's crust to produce reservoirs of high

pressure geothermal steam at temperatures of up to 300şC; the steam is tapped

from 36 boreholes in the Hengilll volcanic area, and fed via insulated pipelines

to the

steam separation plant to extract water, clay and corrosive gases and

deliver dry steam to the power plant for driving high pressure turbine~generators

(see left and right). At a second stage, the steam is re-used to drive

low-pressure turbine~generators, and then via heat-exchangers to heat ground

water for distribution to domestic consumers for space heating and hot water.

Waste water and steam from the turbines is condensed and cooled in cooling

towers for return to ground level streams (Workings of Hellisheiđi geothermal power plant). Hellisheiđi

power plant became operational in steam separation plant to extract water, clay and corrosive gases and

deliver dry steam to the power plant for driving high pressure turbine~generators

(see left and right). At a second stage, the steam is re-used to drive

low-pressure turbine~generators, and then via heat-exchangers to heat ground

water for distribution to domestic consumers for space heating and hot water.

Waste water and steam from the turbines is condensed and cooled in cooling

towers for return to ground level streams (Workings of Hellisheiđi geothermal power plant). Hellisheiđi

power plant became operational in 2006 and has a maximum electrical generating

capacity of 303 MW and 133 MW of thermal energy. In the exhibition centre, a

combination of videos, information panels and glazed viewing galleries looking

down into the turbine~generator halls explained the station's working and the

nature of the Hengill volcanic zone. Here magma intrusions rise closer to the

surface crust, creating reservoirs of high pressure geothermal steam for

exploitation in electricity generation and urban hot water supply. Iceland's

proud boast is that all of its domestic and industrial power requirements are

now geothermally or hydro-generated. Despite however all of the power companies'

disingenuous claims about geothermal energy being clean and sustainable, there

is still a residual pollutant effect: dissolved gases travel to the surface with

geothermal steam, mainly carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulphide with small amounts

of hydrogen, nitrogen and methane, and emissions of these non-condensable

green-house and toxic gases to the atmosphere are still an unavoidable

consequence of geothermal energy production which has yet to be solved. Clearly

the biggest consumers of geothermally generated power are the large scale

aluminium smelters around 2006 and has a maximum electrical generating

capacity of 303 MW and 133 MW of thermal energy. In the exhibition centre, a

combination of videos, information panels and glazed viewing galleries looking

down into the turbine~generator halls explained the station's working and the

nature of the Hengill volcanic zone. Here magma intrusions rise closer to the

surface crust, creating reservoirs of high pressure geothermal steam for

exploitation in electricity generation and urban hot water supply. Iceland's

proud boast is that all of its domestic and industrial power requirements are

now geothermally or hydro-generated. Despite however all of the power companies'

disingenuous claims about geothermal energy being clean and sustainable, there

is still a residual pollutant effect: dissolved gases travel to the surface with

geothermal steam, mainly carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulphide with small amounts

of hydrogen, nitrogen and methane, and emissions of these non-condensable

green-house and toxic gases to the atmosphere are still an unavoidable

consequence of geothermal energy production which has yet to be solved. Clearly

the biggest consumers of geothermally generated power are the large scale

aluminium smelters around

Iceland: bulk bauxite ore is shipped around

the world to Iceland for smelting, taking advantage of the country's cheap

geothermal power, not exactly the greenest of processes, but a source of

enormous profits for the mining companies. Iceland: bulk bauxite ore is shipped around

the world to Iceland for smelting, taking advantage of the country's cheap

geothermal power, not exactly the greenest of processes, but a source of

enormous profits for the mining companies.

Hveragerđi Camping:

in now heavy late afternoon traffic from the capital, we drove on towards Hveragerđi,

with Route 1 losing much height in two sweeping curves down from the high lava

plateau down to the southern coastal plain (click

here for detailed map of route). We recalled Hveragerđi from 1972 as a

small town, full of geothermally heated greenhouses growing fruit and

vegetables. Today the town had grown in size, and we turned off the Ring Road

past the greenhouses to find the campsite in the side streets. The site seemed

large in size, scattered over several camping areas, and already quite full. We

selected a pitch close to the facilities and went to book in. The owner was

unpleasantly officious, and reacted to our request for the customary

seniors' discount with an emphatic No! The price was expensive at 1,500kr/person

plus 800kr for power; he had a monopoly and clearly, with the endless tourist

demand, was making a tidy profit. Facilities were modern but very limited given

the size of the site, and it was another of those over-busy, over-noisy and

un-relaxing sites, with vehicles driving around until late in the evening. from 1972 as a

small town, full of geothermally heated greenhouses growing fruit and

vegetables. Today the town had grown in size, and we turned off the Ring Road

past the greenhouses to find the campsite in the side streets. The site seemed

large in size, scattered over several camping areas, and already quite full. We

selected a pitch close to the facilities and went to book in. The owner was

unpleasantly officious, and reacted to our request for the customary

seniors' discount with an emphatic No! The price was expensive at 1,500kr/person

plus 800kr for power; he had a monopoly and clearly, with the endless tourist

demand, was making a tidy profit. Facilities were modern but very limited given

the size of the site, and it was another of those over-busy, over-noisy and

un-relaxing sites, with vehicles driving around until late in the evening.

A modern garage in Reykjavík with poor service:

since our appointment with the Reykjavík VW garage, Hekla, was not until 3-00pm, we could

take a relaxed morning. Before leaving, we again checked that George's coolant

level was up to normal, and set off back up the spectacular sweeping bends onto

the high lava plateau, with the temperature gauge still behaving erratically.

The sat-nav guided us by a circuitous route into the city, finishing up in the

main Laugarvegur shopping street to park at Hekla garage among all the brand new

VW Golfs. It was one of those glitzy 'modern' garages with a multitude of be-suited 'desk-jockeys' doing little more than playing at their computers, and

just one hard pressed mechanic actually repairing vehicles. We explained to one

of the desk-jockeys George's symptoms and our assumed diagnosis of failed

temperature sensor. Despite however our booking today's appointment 2 days ago,

all that could be done today was to test and report; if a failed sensor was

confirmed, we should have to return again on Monday for replacement fitting, if

they had one in stock. We felt like saying that if the garage employed more

mechanics rather than parasitical desk-jockeys, then more real work could

be done! After a long wait, the faulty sensor diagnosis was confirmed; they had one in

stock which we paid for, and fitting was arranged with a smaller VW garage in Selfoss for Monday. And for all this, we were charged 10,000kr (Ł72)!! But at

least we had a confirmed diagnosis, and George had the replacement part (or so

we thought!) in his glove compartment ready for fitting on Monday.

be-suited 'desk-jockeys' doing little more than playing at their computers, and

just one hard pressed mechanic actually repairing vehicles. We explained to one

of the desk-jockeys George's symptoms and our assumed diagnosis of failed

temperature sensor. Despite however our booking today's appointment 2 days ago,

all that could be done today was to test and report; if a failed sensor was

confirmed, we should have to return again on Monday for replacement fitting, if

they had one in stock. We felt like saying that if the garage employed more

mechanics rather than parasitical desk-jockeys, then more real work could

be done! After a long wait, the faulty sensor diagnosis was confirmed; they had one in

stock which we paid for, and fitting was arranged with a smaller VW garage in Selfoss for Monday. And for all this, we were charged 10,000kr (Ł72)!! But at

least we had a confirmed diagnosis, and George had the replacement part (or so

we thought!) in his glove compartment ready for fitting on Monday.

Solfatara at Hellisheiđi:

extricating ourselves from the city in busy Friday afternoon traffic, we

returned along Route 1 and turned off at Hellisheiđi onto a new section of

tarmaced lane running parallel with the main road, which we hoped would lead to

a geothermal solfatara seen earlier. The lane ended at what seemed the remains

of an erstwhile spa, with a fumarole gushing clouds of high pressure steam from

a pipe-end, and highly active pools of viciously steaming, surging muddy water

surrounded by sulphurous, corrosive sandy mud. Running up behind was a narrow

solfatara valley lined with sulphurous Solfatara at Hellisheiđi:

extricating ourselves from the city in busy Friday afternoon traffic, we

returned along Route 1 and turned off at Hellisheiđi onto a new section of

tarmaced lane running parallel with the main road, which we hoped would lead to

a geothermal solfatara seen earlier. The lane ended at what seemed the remains

of an erstwhile spa, with a fumarole gushing clouds of high pressure steam from

a pipe-end, and highly active pools of viciously steaming, surging muddy water

surrounded by sulphurous, corrosive sandy mud. Running up behind was a narrow

solfatara valley lined with sulphurous yellow-ochre mud,

and a violently active

boiling pool surging into a basin topped by clouds of steam (Photo

16 - Hellisheiđi solfatara) (see above left and right). Alongside was a

perfectly formed mud pot with raised conical sides and boiling mud plopping in

the bottom (see left). And we had this impressive solfatara almost to ourselves, to clamber

carefully alongside for photos as the traffic passed by along the nearby Ring

Road. Back to Route 1 in busy traffic, we paused at

the edge of the Svinahraun plateau to look out from the highpoint across the broad coastal

plain, with the grid of Hveragerđi's streets spread across the valley floor

below, the distant outline of Ingólfsfjall table mountain, and the silhouette of the Westman Islands on the

southern horizon (see right) (Photo

17 - Southern coastal plain). Down

the sweeping bends into Hveragerđi, we returned to the town's campsite and

settled in at our reserved spot. The barbecue was lit for supper, and despite

the noise from all the camping-cars lined up in rows, our corner remained quiet

this evening. yellow-ochre mud,

and a violently active

boiling pool surging into a basin topped by clouds of steam (Photo

16 - Hellisheiđi solfatara) (see above left and right). Alongside was a

perfectly formed mud pot with raised conical sides and boiling mud plopping in

the bottom (see left). And we had this impressive solfatara almost to ourselves, to clamber

carefully alongside for photos as the traffic passed by along the nearby Ring

Road. Back to Route 1 in busy traffic, we paused at

the edge of the Svinahraun plateau to look out from the highpoint across the broad coastal

plain, with the grid of Hveragerđi's streets spread across the valley floor

below, the distant outline of Ingólfsfjall table mountain, and the silhouette of the Westman Islands on the

southern horizon (see right) (Photo

17 - Southern coastal plain). Down

the sweeping bends into Hveragerđi, we returned to the town's campsite and

settled in at our reserved spot. The barbecue was lit for supper, and despite

the noise from all the camping-cars lined up in rows, our corner remained quiet

this evening.

Reykjadalur solfataras in the Hengill

geothermal zone:

a dull start but fine weather was forecast for today's walk up to the

Reykjadalur solfataras. Reserving our space again, we drove out beyond Hveragerđi

to the road's end in lower Reykjadalur, where the parking area was already full and

over-spilling onto the approach road. The route crossed the Verma river to

ascend the slope on a broad, gravelly Reykjadalur solfataras in the Hengill

geothermal zone:

a dull start but fine weather was forecast for today's walk up to the

Reykjadalur solfataras. Reserving our space again, we drove out beyond Hveragerđi

to the road's end in lower Reykjadalur, where the parking area was already full and

over-spilling onto the approach road. The route crossed the Verma river to

ascend the slope on a broad, gravelly path worn by the 1000s of visitors who

daily trudge up into the valley. On the far hill-side, the path followed a warm

stream issuing from hot-springs and steaming solfataras. It then passed a more

vigorously belching mud-pool, constantly bursting and filling the air with steam

reeking of hydrogen sulphide (see left). Now began an unremitting slog up the gravelly

path, winding around from the main valley and gaining 200m of height, followed

by another series of grinding ascents, dipping to cross a side beck, then up

again with startling views down into the depths of the Djúpagil gorge with the

spectacular cascade of a side torrent tumbling down to meet the main Reykjadalsá

river (see right). The mountain scenery surrounding the steep-sided gorge was

truly magnificent, but most of the tourists rushed on by in their haste to reach

the warm bathing pools higher upstream. path worn by the 1000s of visitors who

daily trudge up into the valley. On the far hill-side, the path followed a warm

stream issuing from hot-springs and steaming solfataras. It then passed a more

vigorously belching mud-pool, constantly bursting and filling the air with steam

reeking of hydrogen sulphide (see left). Now began an unremitting slog up the gravelly

path, winding around from the main valley and gaining 200m of height, followed

by another series of grinding ascents, dipping to cross a side beck, then up

again with startling views down into the depths of the Djúpagil gorge with the

spectacular cascade of a side torrent tumbling down to meet the main Reykjadalsá

river (see right). The mountain scenery surrounding the steep-sided gorge was

truly magnificent, but most of the tourists rushed on by in their haste to reach

the warm bathing pools higher upstream.

The path now dropped down into a wider valley,

where Icelandic horses which had ferried tourists up from the lower valley were

tethered (see left), and

crossed the Reykjadalsá on a wooden footbridge for the final

section of ascent into upper Reykjadalur. Erosion damage to the path had been repaired with loose stone chippings, making for uncomfortable

walking. Before the warm water bathing pools of the main upper valley, the path

passed a series of violently active boiling springs and mud pools, with the

emergent boiling water and gases bubbling up and crossed the Reykjadalsá on a wooden footbridge for the final

section of ascent into upper Reykjadalur. Erosion damage to the path had been repaired with loose stone chippings, making for uncomfortable

walking. Before the warm water bathing pools of the main upper valley, the path

passed a series of violently active boiling springs and mud pools, with the

emergent boiling water and gases bubbling up and bursting forth surrounded by

clouds of evil-smelling steam (see right). The springs were now all safely fenced off to

prevent silly tourists scalding themselves. Beyond here, an even more unpleasant

sight sullied this marvellously strange natural landscape, with obese tourists

sprawled along the banks of the warm river-pools like Blackpool beach. We

dropped down to the river for a discrete ritual toe-dip to test the water

temperature: a comfortably warm 40şC. Resuming the path, we continued further

into the upper valley of Klambragil, leaving behind the tourists wallowing in

the warm pools. The surrounding mountain-scape was severe with the scree-draped

craggy slopes of Molddalahnúkar rising sheer above us, and the valley head

enclosed by the cliff-face of Ölkelduhnúkur. The path continued ahead with an

utterly unforgiving grinding ascent up towards Nesjavellir. We branched off at

the foot of the steepest part of the ascent into the uppermost head of Reykjadalur

and the over-towering cliffs of Ölkelduhnúkur, heading over to another large

area of solfataras with its steaming bursting forth surrounded by

clouds of evil-smelling steam (see right). The springs were now all safely fenced off to

prevent silly tourists scalding themselves. Beyond here, an even more unpleasant

sight sullied this marvellously strange natural landscape, with obese tourists

sprawled along the banks of the warm river-pools like Blackpool beach. We

dropped down to the river for a discrete ritual toe-dip to test the water

temperature: a comfortably warm 40şC. Resuming the path, we continued further

into the upper valley of Klambragil, leaving behind the tourists wallowing in

the warm pools. The surrounding mountain-scape was severe with the scree-draped

craggy slopes of Molddalahnúkar rising sheer above us, and the valley head

enclosed by the cliff-face of Ölkelduhnúkur. The path continued ahead with an

utterly unforgiving grinding ascent up towards Nesjavellir. We branched off at

the foot of the steepest part of the ascent into the uppermost head of Reykjadalur

and the over-towering cliffs of Ölkelduhnúkur, heading over to another large

area of solfataras with its steaming

fumaroles (see left) (Photo

18 - Steaming fumaroles in upper Reykjadalur). At last today we could enjoy this wonderfully strange

unnatural landscape in peace, sharing the solitude with a few sheep which

clearly had no objection to grazing sulphur-tasting grass around the

steam-vents. The warm, steamy air attracted midges which swarmed around our

heads and cameras, but despite this we spent a happy hour photographing the boiling, steaming springs

and mud-pools, treading carefully over the fumaroles (see left) (Photo

18 - Steaming fumaroles in upper Reykjadalur). At last today we could enjoy this wonderfully strange

unnatural landscape in peace, sharing the solitude with a few sheep which

clearly had no objection to grazing sulphur-tasting grass around the

steam-vents. The warm, steamy air attracted midges which swarmed around our

heads and cameras, but despite this we spent a happy hour photographing the boiling, steaming springs

and mud-pools, treading carefully over the sulphur-encrusted hot ground. We

recalled similar boiling pools in the nearby Nesjavellir valley, passed during our 1972 climb of Hengill

and recorded on our rather grainy photograph taken 45 years ago, which is

paired

as a nostalgic time-lapse with

its 2017 equivalent taken today (Photo

19 - Reykjadalur boiling pool). We

followed the flow of the infant Reykjadalsá stream, past further hot springs and

mud-pots, into the enclosed gorge at the innermost recess of the valley head (see

below left).

Here the very beginnings of the Reykjadalsá trickled down the rocky chasm,

draining from marshes higher on Ölkelduháls mountain towering above (see right). This

wonderfully lonely spot, in such awe-inspiring mountainous surroundings, away

from the noise and banality of the tourist hordes wallowing in the warm

river-pools, marked today's highlight. sulphur-encrusted hot ground. We

recalled similar boiling pools in the nearby Nesjavellir valley, passed during our 1972 climb of Hengill

and recorded on our rather grainy photograph taken 45 years ago, which is

paired

as a nostalgic time-lapse with

its 2017 equivalent taken today (Photo

19 - Reykjadalur boiling pool). We

followed the flow of the infant Reykjadalsá stream, past further hot springs and

mud-pots, into the enclosed gorge at the innermost recess of the valley head (see

below left).

Here the very beginnings of the Reykjadalsá trickled down the rocky chasm,

draining from marshes higher on Ölkelduháls mountain towering above (see right). This

wonderfully lonely spot, in such awe-inspiring mountainous surroundings, away

from the noise and banality of the tourist hordes wallowing in the warm

river-pools, marked today's highlight.

Beginning our return route, we followed the

course of the infant Reykjadalsá stream, as hot water from boiling springs and

mud-pools along its higher banks flowed in, heating the river water. This led us

across marshy ground to re-join the main path which circled around the left-hand

side of the now widening river. On the far side, steaming hot springs flowed

into the river warming it further, their mineral-rich water depositing and

encrusting the rocks with iron-red staining. At a path junction, we returned

along the far bank of the bathing pools, wading through tourist hordes as they

wallowed in the warm water. Re-crossing the river at the foot-bridge, we

re-joined the outward path for the return walk down-valley. With even greater

numbers of ill-clad, ill-shod tourists coming up the route, treading carelessly

causing further erosion to the ever-widening track, we returned along the main

path. The descent seemed even longer than the seemingly unending ascent, and on

the final lower section, we paused for further Beginning our return route, we followed the

course of the infant Reykjadalsá stream, as hot water from boiling springs and

mud-pools along its higher banks flowed in, heating the river water. This led us

across marshy ground to re-join the main path which circled around the left-hand

side of the now widening river. On the far side, steaming hot springs flowed

into the river warming it further, their mineral-rich water depositing and

encrusting the rocks with iron-red staining. At a path junction, we returned

along the far bank of the bathing pools, wading through tourist hordes as they

wallowed in the warm water. Re-crossing the river at the foot-bridge, we

re-joined the outward path for the return walk down-valley. With even greater

numbers of ill-clad, ill-shod tourists coming up the route, treading carelessly

causing further erosion to the ever-widening track, we returned along the main

path. The descent seemed even longer than the seemingly unending ascent, and on

the final lower section, we paused for further photos at the boiling mud-pools

hot-spot before completing the descent to the parking area. photos at the boiling mud-pools

hot-spot before completing the descent to the parking area.

Down into Hveragerđi, we drove past the site of

the former spouting geyser Gryla, recalled from a gloomy day in 1972; it had

been blocked by the 2008 earthquake which hit Hveragerđi and had

since then stopped spouting. On the way through the town, we paused to photograph

ripening strawberries in Hveragerđi's geothermally heated greenhouses (see

right). Even in

1972, the town had been a noted fruit and vegetable growing place, full of greenhouses heated from Hengill geothermal sources. Back to Hveragerđi Camping, we