|

CAMPING

IN NORWAY 2014 - Kristiansund, the Atlantic Road to Molde, Åndalsnes,

Raumabanen railway

to Dombås, Trollveggen rock face, Ålesund,

and into fjord-land to Hellesylt, Geirangerfjord, Stryn and

Strynevatn: CAMPING

IN NORWAY 2014 - Kristiansund, the Atlantic Road to Molde, Åndalsnes,

Raumabanen railway

to Dombås, Trollveggen rock face, Ålesund,

and into fjord-land to Hellesylt, Geirangerfjord, Stryn and

Strynevatn:

Westwards on E39 to Kristiansund:

the onward E39 from Høgkjølen Camping across high fell-land was well-surfaced

and we were able to make good progress westward to a road junction. Here the

better road turned north leading to nowhere in particular, while E39 became more

narrow and poorly surfaced along the shore of the inner reaches of Vinjefjord.

The hilly peninsula on the far side of the fjord stretched away westwards, cut

through by side fjords to form 3 separate islands towards the tip. E39 crossed

side fjords to reach the large village of Vågalnd, turning south around the

shore of Skålviksfjord and out to the ferry dock at Halsa. From here the 20

minute ferry crossed Halsafjord to Kauestraum, and we joined the few vehicles

and couple of lorries already queuing as the 12-30 ferry was just docking.

|

Click on 3 highlighted areas of map for

details of

Western Norway |

|

Krifast Mainland Connection of bridges and undersea

tunnel at Kristiansund:

over the Straumnes peninsula we crossed the Straumsund bridge to the

island of Aspøya, and around the southern shore reached the first of a trio of

modern civil engineering masterpieces that make up the ensemble of 2 mammoth

bridges and 5km long undersea tunnel, connecting the municipality of Kristiansund via Routes 70 and E39 to the neighbouring islands of Frei, Bergsøya

and Aspøya and the Norwegian mainland - the Krifast Mainland Connection (Kristiansund

fastlands-forbindelse) - see the

Map of the Krifast Mainland Connection to Kristiansund.

The Storting (Norwegian Parliament) authorised construction of the Krifast in October 1988, pledging

39% funding

of the cost with the remainder financed from car ferries during the construction

period and from tolls after completion. At July 1991 the project employed 427 people

and spent 2 million NOK daily on construction. 4 years and 1.1 billion NOK later

in August 1992, Krifast was opened for regular traffic. The balance of

construction costs was covered by tolls payment by December 2012 when the

bridges and tunnel became toll-free.

The Bergsøysund pontoon bridge:

we reached the first of the Krifast main bridges, the 933m (3,061 feet) long

Bergsøysund Bridge which connects the islands of Aspøya and Bergsøya in an

elegant sweeping curve (see left). The unique feature however of this magnificent structure

is that only its 2 ends are anchored into solid rock; the bridge's connecting

curvature is supported on 7 pontoons floating on the 320m deep, almost 1km wide Bergsøy Sound

(see below right). The significance of this pontoon structure was only apparent when

we parked in the lay-by and walked down to the flat fjord-side rocks. From this

vantage point, we had the perfect view looking The Bergsøysund pontoon bridge:

we reached the first of the Krifast main bridges, the 933m (3,061 feet) long

Bergsøysund Bridge which connects the islands of Aspøya and Bergsøya in an

elegant sweeping curve (see left). The unique feature however of this magnificent structure

is that only its 2 ends are anchored into solid rock; the bridge's connecting

curvature is supported on 7 pontoons floating on the 320m deep, almost 1km wide Bergsøy Sound

(see below right). The significance of this pontoon structure was only apparent when

we parked in the lay-by and walked down to the flat fjord-side rocks. From this

vantage point, we had the perfect view looking around the bridge's full sweeping

curvature with its steel lattice-work supporting the road-decking floating on

its 7 huge pontoons in the fjord and spread at regular intervals around the

bridge's 933m width

(Photo 1 - Bergsøysund pontoon bridge). Fishermen were casting their lines from the bridge's

parapet as we walked around to admire the structure. around the bridge's full sweeping

curvature with its steel lattice-work supporting the road-decking floating on

its 7 huge pontoons in the fjord and spread at regular intervals around the

bridge's 933m width

(Photo 1 - Bergsøysund pontoon bridge). Fishermen were casting their lines from the bridge's

parapet as we walked around to admire the structure.

The Gjemnessund suspension bridge:

we crossed the Bergsøysund pontoon bridge and drove around the southern coast of Bergsøya

to reach the next link in the Krifast Mainland Connection, the Gjemnessund

suspension bridge. Perhaps the most visually impressive of the Krifast bridges,

the Gjemnessund suspension bridge links the E39 from the SW tip of Bergsøya

island across to the much fragmented mainland of the Gjemnes municipality. Its

twin towers soar 108m (354 feet) high above the sound with a span of 623m (2,044

feet) between the towers, with the roadway decking arching upwards in an graceful

curve.

We pulled into a nearby parking area at the SW

tip of Bergsøya and walked down under the bridge's mighty piers; traffic passed

over the roadway high above with the noise of aircraft. This was such an

impressive spot from which to view the bridge's structure at close quarters; the

clusters of cable-stays anchored in concrete settings curved upwards towards the

bridges pylons. Being now toll-free, we could drive across the bridge without

charge, and began the long, steep climb under the first tower to the bridge's

lofty apex and down the far slope. Reaching the far shore, we turned off to a

small boat jetty for the panoramic view of the full sweep of this elegant

structure over a foreground of fishing boats

(see left) (Photo 2 - Gjemnessund suspension bridge). Beyond the end of the bridge's

southern approach, E39 disappeared into the mouth of a tunnel. The former road

still existed as a cycle route around to Molde avoiding the tunnel and running

around the coast past a church set on a high bluff overlooking the sound. The

church's graveyard gave a limited view of the bridge's western profile. We pulled into a nearby parking area at the SW

tip of Bergsøya and walked down under the bridge's mighty piers; traffic passed

over the roadway high above with the noise of aircraft. This was such an

impressive spot from which to view the bridge's structure at close quarters; the

clusters of cable-stays anchored in concrete settings curved upwards towards the

bridges pylons. Being now toll-free, we could drive across the bridge without

charge, and began the long, steep climb under the first tower to the bridge's

lofty apex and down the far slope. Reaching the far shore, we turned off to a

small boat jetty for the panoramic view of the full sweep of this elegant

structure over a foreground of fishing boats

(see left) (Photo 2 - Gjemnessund suspension bridge). Beyond the end of the bridge's

southern approach, E39 disappeared into the mouth of a tunnel. The former road

still existed as a cycle route around to Molde avoiding the tunnel and running

around the coast past a church set on a high bluff overlooking the sound. The

church's graveyard gave a limited view of the bridge's western profile.

The Freifjord undersea tunnel:

re-crossing the suspension bridge, we now faced the 3rd of Krifast's major

structures, the 5.1km (3.2 miles) long Freifjord undersea tunnel, which passes

134m (440 feet) below the sea level of Freifjord Sound between the islands of Bergsøya

and Frei on Route 70's approach to Kristiansund (see right). The tunnel descends very

steeply for its first kilometre then levels out at its deepest point for 3kms

before rising steeply for its final kilometre to its exit on Frei island. The

1km ascent slopes at either end out of the tunnel's depths are both 3 lane

allowing overtaking of slow-moving traffic. It took 5 minutes to pass through

the undersea tunnel before we drove on across the width of Frei. The Freifjord undersea tunnel:

re-crossing the suspension bridge, we now faced the 3rd of Krifast's major

structures, the 5.1km (3.2 miles) long Freifjord undersea tunnel, which passes

134m (440 feet) below the sea level of Freifjord Sound between the islands of Bergsøya

and Frei on Route 70's approach to Kristiansund (see right). The tunnel descends very

steeply for its first kilometre then levels out at its deepest point for 3kms

before rising steeply for its final kilometre to its exit on Frei island. The

1km ascent slopes at either end out of the tunnel's depths are both 3 lane

allowing overtaking of slow-moving traffic. It took 5 minutes to pass through

the undersea tunnel before we drove on across the width of Frei.

Alanten Turistsenter-Camping at Kristiansund: the port-town of Kristiansund is spread across a complex

of 3 islands, Nordland, Gomaland and Innland, with its harbour set in the sound

between the islands. Crossing Nordland, we passed several of the town's marine

engineering works which now support Norway's off-shore oil and gas industry.

Although at this stage, Kristiansund's topography was totally bemusing, our sat-nav

guided us over to Gomaland island and around the town's northern side, eventually

reaching Alanten Turistsenter and Camping, our base for our stay in

Kristiansund. The girl at reception was smilingly welcoming and helpful,

providing a town-plan, explaining the walk into Kristiansund and its places of

interest, and pointing out the camping areas and facilities hut; the nightly

all-inclusive charge of 200 NOK seemed almost too good to be true, but more of

that later! We selected a pitch only to discover that power points were

non-functional, and eventually settled into another corner, hoping this would be

quiet and looking forward to a much-needed day in camp tomorrow (see left). The evening was

more dusky than ever with the sun setting soon after 10-00pm and not rising

until 5-00am. Alanten Turistsenter-Camping at Kristiansund: the port-town of Kristiansund is spread across a complex

of 3 islands, Nordland, Gomaland and Innland, with its harbour set in the sound

between the islands. Crossing Nordland, we passed several of the town's marine

engineering works which now support Norway's off-shore oil and gas industry.

Although at this stage, Kristiansund's topography was totally bemusing, our sat-nav

guided us over to Gomaland island and around the town's northern side, eventually

reaching Alanten Turistsenter and Camping, our base for our stay in

Kristiansund. The girl at reception was smilingly welcoming and helpful,

providing a town-plan, explaining the walk into Kristiansund and its places of

interest, and pointing out the camping areas and facilities hut; the nightly

all-inclusive charge of 200 NOK seemed almost too good to be true, but more of

that later! We selected a pitch only to discover that power points were

non-functional, and eventually settled into another corner, hoping this would be

quiet and looking forward to a much-needed day in camp tomorrow (see left). The evening was

more dusky than ever with the sun setting soon after 10-00pm and not rising

until 5-00am.

The following day we discovered the full scale

of Alanten Turistsenter and Camping's inadequacies, and the reason for its

apparently reasonable charge. The camping areas were careworn with inadequate or

unserviceable power supplies, and the facilities hopelessly limited: with just 2

WCs and showers for such a busy campsite, queues were inevitable; an apology for

a kitchen consisted of one outside wash-up sink and an electric ring, and

the wi-fi signal was too weak to reach the camping area. But the worst feature

was the abominable noise produced by the ventilation system which reverberated

around the entire camping area, making life intolerable for those camped nearby.

Our pitch around the corner escaped this noise but was not immune from the

overwhelmingly intrusive disturbance of The following day we discovered the full scale

of Alanten Turistsenter and Camping's inadequacies, and the reason for its

apparently reasonable charge. The camping areas were careworn with inadequate or

unserviceable power supplies, and the facilities hopelessly limited: with just 2

WCs and showers for such a busy campsite, queues were inevitable; an apology for

a kitchen consisted of one outside wash-up sink and an electric ring, and

the wi-fi signal was too weak to reach the camping area. But the worst feature

was the abominable noise produced by the ventilation system which reverberated

around the entire camping area, making life intolerable for those camped nearby.

Our pitch around the corner escaped this noise but was not immune from the

overwhelmingly intrusive disturbance of

excavating diggers. Only the pleasant

welcome given by the young receptionist prevented the place from getting the

first negative rating of the trip! We put up with the noise levels and made the

most of our day in camp. excavating diggers. Only the pleasant

welcome given by the young receptionist prevented the place from getting the

first negative rating of the trip! We put up with the noise levels and made the

most of our day in camp.

Kristiansund: we woke to clear sky and sunny morning for our visit

to Kristiansund today, and set off to walk into the town. Set around its natural

harbour formed within the sound enclosed by the 3 islands across which the town

spreads, Kristiansund has prospered since the 17th century from cod fishing and

as a centre for the production of Klippfisk. The salted, dried cod was

processed traditionally by the town's womenfolk: gutted and de-headed while

the boats were still at sea, the flattened fish bodies were cleaned in the

shallows by the harbour (a desperate job in the freezing waters of winter),

salted and laid out to dry in the sun and wind on flat shore-side rocks;

this gave the dried cod the name Klippfisk from the Norwegian word

klipper meaning rocks. English merchants financed the klippfisk warehouses,

and a huge export trade developed with Portugal and Spain which still continues.

Today modern electric dryers have taken over from the traditional but

labour-intensive hand-washing and drying of yesteryear.

Kristiansund like so many Norwegian ports and

towns was bombed to total destruction by the Luftwaffe in April 1940, and 70% of

the town's building were reduced to ruins The town was rebuilt after the war,

and cod processing remains an important industry for Kristiansund with a large

proportion of Norway's Klippfisk exports produced in and around the town.

But since the discovery and exploitation of North Sea oil and gas, Kristiansund

has developed as one of Norway's major centres for servicing the oil and gas

rigs, with a huge partly state-financed terminal built just outside the town.

Our visit to Kristiansund: we walked down from the campsite to an

underpass where a pathway led past the marina and through what had been a 19th

century shipyard-museum, now more of a maritime junkyard full of the rusting

remains of ships (see above left). As a prelude to visiting the town and port, we walked from the

main street up through a park to find a route up to the Varden observation tower

on the hill top for its views over Kristiansund's islands and the Atlantic

coast. After what seemed an unending climb around pathways winding up the

hillside, we finally reached the ornamental white tower, surprised to find it

open and free. From its top, there was a panoramic view over the harbour (see

right), but more interestingly on the seaward side to the tiny island, skerries and

lighthouse of Grip. This former fishing settlement 14kms off the coast is now a

tourist attraction with boats from Kristiansund taking visitors out to the now

abandoned village.

Back down into the city's main street Langveien we

visited the modern towered structure of the Kirkelandet church built in 1964 to

replace the town church flattened by WW2 German bombing (see left). The lines of the

church's plainly stark interior led the eye to the full height east-end stained glass

window

(Photo 3 - Kristiansund's Kirkelandet church)

(see right). As modern church architecture goes it Back down into the city's main street Langveien we

visited the modern towered structure of the Kirkelandet church built in 1964 to

replace the town church flattened by WW2 German bombing (see left). The lines of the

church's plainly stark interior led the eye to the full height east-end stained glass

window

(Photo 3 - Kristiansund's Kirkelandet church)

(see right). As modern church architecture goes it was certainly impressive, more so

than Bodø's ascetic concrete barn of a cathedral. Outside, rose gardens

scented the air as we walked down the street towards the main square of Kongens

Plass for details of the Atlantic road from the helpful TIC. The main street

turned off to the modern bridge crossing to Innlandet island, but we continued

ahead down to the harbour where 2 huge oil rig construction or servicing ships

over-topped with cranes were moored in the sound. Following the

waterfront around, we reached the main pier of Piren with the Kristiansund's iconic statue

of Klippfiskkjerringa, the fish-wife carrying her basket of klippfisk,

recalling the days of these poor women's hard labours washing the fish in

the freezing shallows and laying it to dry on the harbour rocks (Photo 4 - Klippfiskkjerringa statue by Kristiansund's waterfront). The romantic

imagery presented by the modern tourist industry belies the grim working

conditions and low pay of the fish-drying women whose toils lined the pockets of

fish merchants. As we sat to eat our sandwich lunch by the Piren war memorial,

the stumpy little Sundbåt harbour ferry pulled in at its pier-side mooring. Now

operated by Kristiansund Commune, the Sundbåts which chug back and forth across

the harbour between the town's 3 islands, are claimed as 'the world's oldest

public transport system in uninterrupted use'

(Photo 5 - Kristiansund's harbour ferry (Sundbåt))

(see below left). was certainly impressive, more so

than Bodø's ascetic concrete barn of a cathedral. Outside, rose gardens

scented the air as we walked down the street towards the main square of Kongens

Plass for details of the Atlantic road from the helpful TIC. The main street

turned off to the modern bridge crossing to Innlandet island, but we continued

ahead down to the harbour where 2 huge oil rig construction or servicing ships

over-topped with cranes were moored in the sound. Following the

waterfront around, we reached the main pier of Piren with the Kristiansund's iconic statue

of Klippfiskkjerringa, the fish-wife carrying her basket of klippfisk,

recalling the days of these poor women's hard labours washing the fish in

the freezing shallows and laying it to dry on the harbour rocks (Photo 4 - Klippfiskkjerringa statue by Kristiansund's waterfront). The romantic

imagery presented by the modern tourist industry belies the grim working

conditions and low pay of the fish-drying women whose toils lined the pockets of

fish merchants. As we sat to eat our sandwich lunch by the Piren war memorial,

the stumpy little Sundbåt harbour ferry pulled in at its pier-side mooring. Now

operated by Kristiansund Commune, the Sundbåts which chug back and forth across

the harbour between the town's 3 islands, are claimed as 'the world's oldest

public transport system in uninterrupted use'

(Photo 5 - Kristiansund's harbour ferry (Sundbåt))

(see below left).

Along the main waterfront

passing 2 typically

ostentatious Russian cruise boats moored there and the rusty hulk of another oil

rig servicing vessel, we reached the Hurtigruten quay, but this was all locked

up and deserted until the south-bound liner arrived at 4-30 this afternoon. Back

along Along the main waterfront

passing 2 typically

ostentatious Russian cruise boats moored there and the rusty hulk of another oil

rig servicing vessel, we reached the Hurtigruten quay, but this was all locked

up and deserted until the south-bound liner arrived at 4-30 this afternoon. Back

along to Piren, we boarded the waiting Sundbåt to cross the harbour to

Gamle Byen on Innlandet. The honnør fare was 15 NOK and it took just a

couple of minutes to chug across the width of the harbour to the outer island,

and we spent a pleasant hour wandering around the lanes of the Old Town past all

the attractive and brightly coloured old wooden houses and cottages (Photo

6 - Gamle Byen wooden houses) (see below right). The view

from the hillside lanes down across the harbour made the climb worthwhile. Up

the hillside street, we located the path leading up onto the hill-top Bautaen

look-out point created in 1908 to mark the anniversary of a Napoleonic Wars

naval skirmish in 1808 when local militia had given a bloody nose to

2 Royal Navy frigates who saw the port of Kristiansund as an easy target for

attack. The path curved steeply up to the look-out which was duly decorated with

cannons from the 1908 celebrations, and gave a magnificent bird's eye panorama

over the town, its 3 islands and oil rig servicing ships (see right) (Photo

7 - Oil-rig servicing ship in Kristiansund harbour), and the stubby little Sundbåts crossing the harbour (Photo

8 - Sundbåt crossing Kristiansund harbour) (see below left). to Piren, we boarded the waiting Sundbåt to cross the harbour to

Gamle Byen on Innlandet. The honnør fare was 15 NOK and it took just a

couple of minutes to chug across the width of the harbour to the outer island,

and we spent a pleasant hour wandering around the lanes of the Old Town past all

the attractive and brightly coloured old wooden houses and cottages (Photo

6 - Gamle Byen wooden houses) (see below right). The view

from the hillside lanes down across the harbour made the climb worthwhile. Up

the hillside street, we located the path leading up onto the hill-top Bautaen

look-out point created in 1908 to mark the anniversary of a Napoleonic Wars

naval skirmish in 1808 when local militia had given a bloody nose to

2 Royal Navy frigates who saw the port of Kristiansund as an easy target for

attack. The path curved steeply up to the look-out which was duly decorated with

cannons from the 1908 celebrations, and gave a magnificent bird's eye panorama

over the town, its 3 islands and oil rig servicing ships (see right) (Photo

7 - Oil-rig servicing ship in Kristiansund harbour), and the stubby little Sundbåts crossing the harbour (Photo

8 - Sundbåt crossing Kristiansund harbour) (see below left).

Back down the hill we boarded the 3-15pm Sundbåt

to cross firstly to the 3rd island of Nordlandet whose hillside was also lined

with attractive wooden houses, then on across the harbour to Gomalandet as the

coastal express ferry (Kystekspressen) from Trondheim arrived at the port.

The Sundbåt Back down the hill we boarded the 3-15pm Sundbåt

to cross firstly to the 3rd island of Nordlandet whose hillside was also lined

with attractive wooden houses, then on across the harbour to Gomalandet as the

coastal express ferry (Kystekspressen) from Trondheim arrived at the port.

The Sundbåt dropped us at the quay-stop by the Klippfisk Museum, our next

stopping point. Housed in a venerable old wooden fish warehouse, the Milnbrygge,

named after the 1772 English merchant owner Walter Miln (Photo

9 - Kristiansund Klippfisk Museum), the museum claims to

document the history of the klippfisk industry in Kristiansund from the 18th

century to post-WW2, and the thriving export trade of bacalao to

Mediterranean countries. The conserved wooden wharf was an admirable

masterpiece, which is more than could be said for the museum. You could wander

around parts of the un-translated exhibition and watch their klippfisk video for

free, or pay 70 NOK for an indifferent collection of old photos upstairs; the choice was an easy one! And that was the much promoted Klippfisk Museum. dropped us at the quay-stop by the Klippfisk Museum, our next

stopping point. Housed in a venerable old wooden fish warehouse, the Milnbrygge,

named after the 1772 English merchant owner Walter Miln (Photo

9 - Kristiansund Klippfisk Museum), the museum claims to

document the history of the klippfisk industry in Kristiansund from the 18th

century to post-WW2, and the thriving export trade of bacalao to

Mediterranean countries. The conserved wooden wharf was an admirable

masterpiece, which is more than could be said for the museum. You could wander

around parts of the un-translated exhibition and watch their klippfisk video for

free, or pay 70 NOK for an indifferent collection of old photos upstairs; the choice was an easy one! And that was the much promoted Klippfisk Museum.

Behind the Milnbrygge wharf, we clambered up onto

the flat rocks firstly to see the evident white staining from generations of

usage for drying klippfisk, and then to find a high vantage point with clear

view across the harbour from which to watch the arrival of the south-bound

Hurtigrute due at 4-30pm. In the distance the Hurtigrute's horn sounded

announcing its imminent arrival, and around the sound between Innlandet and

Kirkelandet, M/S Polarlys steamed majestically into Kristiansund harbour

(see below right) to dock at its quay immediately opposite where we stood on the klippfisk rocks (Photo

10 - Hurtigrute M/S Polarlys docking at Kristiansund).

We took our photos of the ship which we had seen earlier at the northern port of Berlevåg, then continued around towards the marina where from the quay-side we

watched M/S Polarlys back gracefully

from her mooring and sail away around the sound. Beyond a ship repair yard

where a rusty hulk was being renovated, the lane led around the eastern side of

the harbour to our starting point from this morning, and back up to the

campsite. Today had given us a fascinating insight into Kristiansund's long cod

fishing and klippfisk processing traditions which continue today, its wartime

destruction and German occupation, and its modern day renewal and prosperity as

a major port and servicing centre for Norway's North Sea oil and gas exploitation

(see below left). It was

a gritty, hard-working and attractive port-city; we liked it a lot. renovated, the lane led around the eastern side of

the harbour to our starting point from this morning, and back up to the

campsite. Today had given us a fascinating insight into Kristiansund's long cod

fishing and klippfisk processing traditions which continue today, its wartime

destruction and German occupation, and its modern day renewal and prosperity as

a major port and servicing centre for Norway's North Sea oil and gas exploitation

(see below left). It was

a gritty, hard-working and attractive port-city; we liked it a lot.

Byskogen Camping, Kristiansund: our original plan was to move

today, but rain had poured all night, and this morning the sky was dismally

overcast with rain cloud; it was still pouring. This certainly was not a day even

to contemplate the Atlantic Road, which tourist promotion describes as The

world's most beautiful drive. Given the forecast for continuing rain, the only

sensible thing was to sit it out in Kristiansund for another day and hope for

better weather tomorrow. We had chosen Alanten Turistsenter and Camping as a

base since it was within walking distance of the town, but with all the noise

disturbance and hopelessly inadequate, care-worn facilities, we decided to move

to Kristiansund's other campsite, Byskogen Camping over by the airfield. Having

re-stocked with provisions at a Co-op Extra hypermarket, we turned up to

Byskogen Camping. Set in a verdant grove surrounded by pine trees, the campsite

was deserted when we arrived. But the reception and service building were open

and facilities modern and clean with homely kitchen/common room and site-wide

wi-fi; we found a quiet corner of the camping area and settled in. The only

noise from the airfield was an occasional helicopter, rather more preferable

than the constant noise of diggers at Alanten Turistsenter! The weather remained overcast and the air

distinctly cooler, but the forecast was better for tomorrow when we should drive

the Atlantic Road around the spectacular west coast. Byskogen Camping, Kristiansund: our original plan was to move

today, but rain had poured all night, and this morning the sky was dismally

overcast with rain cloud; it was still pouring. This certainly was not a day even

to contemplate the Atlantic Road, which tourist promotion describes as The

world's most beautiful drive. Given the forecast for continuing rain, the only

sensible thing was to sit it out in Kristiansund for another day and hope for

better weather tomorrow. We had chosen Alanten Turistsenter and Camping as a

base since it was within walking distance of the town, but with all the noise

disturbance and hopelessly inadequate, care-worn facilities, we decided to move

to Kristiansund's other campsite, Byskogen Camping over by the airfield. Having

re-stocked with provisions at a Co-op Extra hypermarket, we turned up to

Byskogen Camping. Set in a verdant grove surrounded by pine trees, the campsite

was deserted when we arrived. But the reception and service building were open

and facilities modern and clean with homely kitchen/common room and site-wide

wi-fi; we found a quiet corner of the camping area and settled in. The only

noise from the airfield was an occasional helicopter, rather more preferable

than the constant noise of diggers at Alanten Turistsenter! The weather remained overcast and the air

distinctly cooler, but the forecast was better for tomorrow when we should drive

the Atlantic Road around the spectacular west coast.

The Atlantic Ocean Undersea Tunnel to Averøya: after a peaceful night at Byskogen, we woke to a

clear sky and sunny morning. The morning internal flight for Oslo was just taking off as

we departed to drive back through the northern outskirts of Kristiansund and

turn off onto Route 64 at the entrance to the Atlanterhavs-tunnelen (Atlantic

Ocean Tunnel). The 5.7km (3.5 miles) long tunnel connecting Kristiansund's

Kirkelandet island to Averøya runs beneath Bremsnesfjord reaching a depth of

250m below sea level, making it one of the world's deepest undersea tunnels.

Construction began in 2006, breaking through in March 2009; problems with

rock-falls, cave-ins and water leaks caused delays (although when you are

driving through, you prefer not to know this!) and consequent cost-overrun, and

the tunnel opened in December 2009. The 1km long descent and ascent at a

gradient of 10% have dual lanes for overtaking. 70% of the tunnel's 635 million

NOK construction cost is to be recovered from tolls which are still in operation

with an anticipated pay-back period of 18 years. The Atlantic Ocean Undersea Tunnel to Averøya: after a peaceful night at Byskogen, we woke to a

clear sky and sunny morning. The morning internal flight for Oslo was just taking off as

we departed to drive back through the northern outskirts of Kristiansund and

turn off onto Route 64 at the entrance to the Atlanterhavs-tunnelen (Atlantic

Ocean Tunnel). The 5.7km (3.5 miles) long tunnel connecting Kristiansund's

Kirkelandet island to Averøya runs beneath Bremsnesfjord reaching a depth of

250m below sea level, making it one of the world's deepest undersea tunnels.

Construction began in 2006, breaking through in March 2009; problems with

rock-falls, cave-ins and water leaks caused delays (although when you are

driving through, you prefer not to know this!) and consequent cost-overrun, and

the tunnel opened in December 2009. The 1km long descent and ascent at a

gradient of 10% have dual lanes for overtaking. 70% of the tunnel's 635 million

NOK construction cost is to be recovered from tolls which are still in operation

with an anticipated pay-back period of 18 years.

Kvernes stave church: we descended

into the tunnel at an alarming rate of fall and speed, thankful that Saturday

morning traffic was light; the re-ascent seemed even steeper. Emerging into

daylight at the toll-booths at the Averøya end, we faced a charge of 125 NOK (£12.50)

with no honnør reduction, our

contribution to the tunnel's construction cost recovery. We had also emerged

into an entirely different landscape from the Kristiansund islands: Averøya's knobbly, tree-covered fell-scape

looked delightful on a bright morning, especially against the exquisite blue of the Ocean away to our

right. A diversion brought us down to Bremnes quay from where the pre-tunnel

ferry had provided the only western road access to Kristiansund; today a sign warned

hopefuls that 'This ferry no longer operates' - so there! At the busy village of Bruhagen, we turned off from Route 64 onto the minor FV-247 lane which threaded

around the shore of Bremnesfjord down to the SE point of Averøya island and the

delightful farming village of Kvernes, where the ancient timber Kvernes

stave-church and its 19th century successor stood on the turf-lawned hill-side

looking out across the breadth of Kvernesfjord (see left). Kvernes stave church: we descended

into the tunnel at an alarming rate of fall and speed, thankful that Saturday

morning traffic was light; the re-ascent seemed even steeper. Emerging into

daylight at the toll-booths at the Averøya end, we faced a charge of 125 NOK (£12.50)

with no honnør reduction, our

contribution to the tunnel's construction cost recovery. We had also emerged

into an entirely different landscape from the Kristiansund islands: Averøya's knobbly, tree-covered fell-scape

looked delightful on a bright morning, especially against the exquisite blue of the Ocean away to our

right. A diversion brought us down to Bremnes quay from where the pre-tunnel

ferry had provided the only western road access to Kristiansund; today a sign warned

hopefuls that 'This ferry no longer operates' - so there! At the busy village of Bruhagen, we turned off from Route 64 onto the minor FV-247 lane which threaded

around the shore of Bremnesfjord down to the SE point of Averøya island and the

delightful farming village of Kvernes, where the ancient timber Kvernes

stave-church and its 19th century successor stood on the turf-lawned hill-side

looking out across the breadth of Kvernesfjord (see left).

The stav-kirke at Kvernes

was built around 1300 (Photo

11 - Kvernes stave-church). The original church consisted of just the present nave,

its roof supported by 10 staves and its sturdy timber walls shored up by

external diagonal props. In 1663 the earlier stave-constructed chancel was

replaced by the present larger log-construction east-end, its walls decorated

with painted Biblical scenes, and a west-end The stav-kirke at Kvernes

was built around 1300 (Photo

11 - Kvernes stave-church). The original church consisted of just the present nave,

its roof supported by 10 staves and its sturdy timber walls shored up by

external diagonal props. In 1663 the earlier stave-constructed chancel was

replaced by the present larger log-construction east-end, its walls decorated

with painted Biblical scenes, and a west-end

baptistery added. In the following

decade, the then pastor, Rev Anders Erikson, at his own expense had the nave and

baptistery walls and ceiling decorated with acanthus leaf paintings (Photo

12 - Kvernes stave church wall-paintings); remarkably

these decorations still survive though with some water damage. The stave-church

had passed from royal to parish ownership from the 18th century, and narrowly

survived demolition when the new church was built alongside in 1893. It was saved

and bought by the Society for Preservation of Ancient Monuments in 1893, and

today stands in remarkable condition with most of its original decoration still

intact. baptistery added. In the following

decade, the then pastor, Rev Anders Erikson, at his own expense had the nave and

baptistery walls and ceiling decorated with acanthus leaf paintings (Photo

12 - Kvernes stave church wall-paintings); remarkably

these decorations still survive though with some water damage. The stave-church

had passed from royal to parish ownership from the 18th century, and narrowly

survived demolition when the new church was built alongside in 1893. It was saved

and bought by the Society for Preservation of Ancient Monuments in 1893, and

today stands in remarkable condition with most of its original decoration still

intact.

The charming young guide nervously began her

description of the church's history and decorations, and showed us the church's

other treasures: a 300 year old votive ship said to have been plundered from a

Swedish church (see right), and the 15th century hybrid altar-piece, Catholic in origin with

carved figures of Mary and saints, which remarkably survived the Lutheran

bigotry of the Reformation having a florally decorated carved surround added in

1695 (see left). The chancel screen was decorated with the Danish King Christian IV's

royal monogram. We complemented this charmingly demur young lady for her

knowledgeable commentary and faultless command of

English, to which she modestly replied, "I had a good teacher". This was another delightfully

memorable encounter. We took our photographs inside and outside the

stave-church, and our eyes were also drawn in the opposite direction where the Gjemnessund

suspension bridge, which we had recently crossed, was just visible in the misty

distance across the fjord (Photo

13 - Gjemnessund suspension bridge across Bremnesfjord).

The

Atlantic Road: along the southern shore of Averøya, we passed a

series of dairy farms with cattle grazing and silage being cut or already

stacked in bales ready for next winter. It was a lovely peaceful setting,

looking out across Kvernesfjord to the mountainous mainland coast opposite. The

lane re-joined Route 64 at Karvåg at the start of the spectacular 8 km long

Atlantic Road, built over an archipelago of islands and skerries across the

mouth of Lauvøyfjord, linked by causeways and a sequence of 8 bridges, the most

prominent being the high-arching, artistically curving Storseisundet Bridge (see

right). The

route was originally planned as a railway line in the early 20th century, but

this project was abandoned. Planning of a road route began in 1970 and

construction began in 1983. During the 6 year construction period, the area was

hit by 12 hurricanes along this wildly exposed stretch of the Atlantic

coastline. The road opened in July 1989 at a total cost of The

Atlantic Road: along the southern shore of Averøya, we passed a

series of dairy farms with cattle grazing and silage being cut or already

stacked in bales ready for next winter. It was a lovely peaceful setting,

looking out across Kvernesfjord to the mountainous mainland coast opposite. The

lane re-joined Route 64 at Karvåg at the start of the spectacular 8 km long

Atlantic Road, built over an archipelago of islands and skerries across the

mouth of Lauvøyfjord, linked by causeways and a sequence of 8 bridges, the most

prominent being the high-arching, artistically curving Storseisundet Bridge (see

right). The

route was originally planned as a railway line in the early 20th century, but

this project was abandoned. Planning of a road route began in 1970 and

construction began in 1983. During the 6 year construction period, the area was

hit by 12 hurricanes along this wildly exposed stretch of the Atlantic

coastline. The road opened in July 1989 at a total cost of

122 million NOK of

which 25% was to be financed by tolls, to be recovered over an expected 15 year

period. In fact, with greater than expected usage by both local and tourist

traffic, the debt had been paid off by 1999 when tolls ended. The Atlantic Road is now

designated as a National Tourist Route

and was voted Norwegian Construction Project of the Century in 2005 by the

Norwegian construction industry. Click here for a

Detailed map of the Atlantic Road 122 million NOK of

which 25% was to be financed by tolls, to be recovered over an expected 15 year

period. In fact, with greater than expected usage by both local and tourist

traffic, the debt had been paid off by 1999 when tolls ended. The Atlantic Road is now

designated as a National Tourist Route

and was voted Norwegian Construction Project of the Century in 2005 by the

Norwegian construction industry. Click here for a

Detailed map of the Atlantic Road

With the sun still shining brightly, we began our

transit of the Atlantic road from Karvåg over the 115m long Lille Lauvøysund

Bridge onto the island of Litllauvøya, then over the 52m long Store Lauvøysund

Bridge to Storlauvøya island. Across a causeway and the 52m long Geitøysundet

Bridge onto the island of Geitøya, we got the first distant glimpse of the

high-arching Storseisundet Bridge's renowned curvature. The road now curved

across the larger islands of Eldhusøya and Lyngholmen to reach the smaller

island of Ildhusøya, the closest point to the approaching curving bridge where

we pulled into a parking area. Here a cleverly constructed walk-way ran around

the outer seaward side of the islet giving perfect views of the curving Storseisundet

Bridge ahead. Sections of the fencing were low so that visitors could walk down

to the shore-line for closer views of the bridge. The islet's peaty moorland

surface was wet from recent rains and covered with heather, but by scrambling up

onto the high point we had the perfect 'helicopter' photographic view looking

across to the bridge

(Photo

14 - Storseisundet Bridge). The elegantly curving structure was by this time of early

afternoon still partly in shade; the time for photographing the bridge to best

advantage would have been early evening when the sun, further over to the west,

would light the face of Storseisundet Bridge.

We began our crossing of steeply sloping,

curvature of Storseisundet Bridge, but as always the view from road level gave

little impression of the bridge's scale and artistic qualities. Across its

cantilevered 260m length onto Flatskjæret islet, we pulled into the next lay-by

and scrambled up onto the high point. This gave further views looking northwards

to Storseisundet Bridge, and to the south over the 3 interconnected sections of

Hulvågen Bridges which led 293m across onto Hulvågen island

(see above left) (Photo

15 - Three section Hulvågen Bridge). Walk-ways along

both sides of the bridges were crowded with fishermen. Across the 3 bridges to

the next island, we again paused at a lay-by where the shore-side rocks gave one

of the Road's best views looking northward across the Hulvågen Bridges backed by

the distant curvature of Storseisundet Bridge (see left and below right) (Photo

16 - Storseisundet Bridge from the south). The road now continued across the

larger islands of Skarvøya and Strausholmen, and over the 119m wide

Vevangstraumen Bridge finally to reach the Eida mainland at the hamlet of

Vevang. There inevitably was a lot of tourist traffic on a sunny Saturday

afternoon, but the route so ingeniously spanning the mouth of the mouth of Lauvøyfjord,

with its impressive array of bridges and viewpoints, had been a thoroughly

engaging experience. We had been very lucky having such clear weather for

today's spectacular journey. We began our crossing of steeply sloping,

curvature of Storseisundet Bridge, but as always the view from road level gave

little impression of the bridge's scale and artistic qualities. Across its

cantilevered 260m length onto Flatskjæret islet, we pulled into the next lay-by

and scrambled up onto the high point. This gave further views looking northwards

to Storseisundet Bridge, and to the south over the 3 interconnected sections of

Hulvågen Bridges which led 293m across onto Hulvågen island

(see above left) (Photo

15 - Three section Hulvågen Bridge). Walk-ways along

both sides of the bridges were crowded with fishermen. Across the 3 bridges to

the next island, we again paused at a lay-by where the shore-side rocks gave one

of the Road's best views looking northward across the Hulvågen Bridges backed by

the distant curvature of Storseisundet Bridge (see left and below right) (Photo

16 - Storseisundet Bridge from the south). The road now continued across the

larger islands of Skarvøya and Strausholmen, and over the 119m wide

Vevangstraumen Bridge finally to reach the Eida mainland at the hamlet of

Vevang. There inevitably was a lot of tourist traffic on a sunny Saturday

afternoon, but the route so ingeniously spanning the mouth of the mouth of Lauvøyfjord,

with its impressive array of bridges and viewpoints, had been a thoroughly

engaging experience. We had been very lucky having such clear weather for

today's spectacular journey.

The fishing village of Bud and Bjølstad Camping: turning

off along a minor lane around Hustadvika Bay, the lane passed through farming

countryside, hamlets and the larger village of Farstad, winding its way around

the coast eventually to reach the large fishing village of Bud, where klippfisk

is still produced. We paused here and walked up to the preserved remains of a

huge WW2 German coastal battery on the headland looking down on Bud's fishing

harbour. Few boats seemed now to work from here, and these days tourism was

clearly the predominant industry.

Driving on along the coast through the small town of Elnesvågen, a

thoroughly unattractive place dominated by a huge chemical plant on the

fjord-side, we passed around the head of Malmefjord and turned off to tonight's

campsite, Bjølstad Camping. The place was sited on a steep hill-side sloping

down to the fjord with several terraced levels. We settled into the one

remaining space on a flatter level near to the service house. With its sloping

pitches, old-fashioned facilities, and worst of all noisy atmosphere, Bjølstad

Camping could at best only be described as mediocre, but would serve for an

overnight stop. The fishing village of Bud and Bjølstad Camping: turning

off along a minor lane around Hustadvika Bay, the lane passed through farming

countryside, hamlets and the larger village of Farstad, winding its way around

the coast eventually to reach the large fishing village of Bud, where klippfisk

is still produced. We paused here and walked up to the preserved remains of a

huge WW2 German coastal battery on the headland looking down on Bud's fishing

harbour. Few boats seemed now to work from here, and these days tourism was

clearly the predominant industry.

Driving on along the coast through the small town of Elnesvågen, a

thoroughly unattractive place dominated by a huge chemical plant on the

fjord-side, we passed around the head of Malmefjord and turned off to tonight's

campsite, Bjølstad Camping. The place was sited on a steep hill-side sloping

down to the fjord with several terraced levels. We settled into the one

remaining space on a flatter level near to the service house. With its sloping

pitches, old-fashioned facilities, and worst of all noisy atmosphere, Bjølstad

Camping could at best only be described as mediocre, but would serve for an

overnight stop.

Molde and the panoramic peak-land view from

Varden viewpoint: back to Route 64 the following morning, we turned

south avoiding a toll tunnel through high fell-land by taking the old road

around a side-valley, to approach the small port-town of Molde. We parked at the

fjord-side central square to enquire at the TIC about the route up onto the

Varden viewpoint above the town. Following our marked-up street plan steeply

uphill through a residential area, we reached the end of the tarmaced lane; a

gravelled road rose even more steeply up the hill-side eventually ending at a

café on the hill's summit. From here the view across the town, fjord and islands

was truly breath-taking with a panoramic skyline to the south said to encompass

222 peaks (Photo

17 - Varden peak-lined panorama). We did not attempt to count them all but took our photos instead with

the now bright sunlight sparkling across the fjord and dramatic cloud-scape to

enhance the panorama of peaks (see left). Molde and the panoramic peak-land view from

Varden viewpoint: back to Route 64 the following morning, we turned

south avoiding a toll tunnel through high fell-land by taking the old road

around a side-valley, to approach the small port-town of Molde. We parked at the

fjord-side central square to enquire at the TIC about the route up onto the

Varden viewpoint above the town. Following our marked-up street plan steeply

uphill through a residential area, we reached the end of the tarmaced lane; a

gravelled road rose even more steeply up the hill-side eventually ending at a

café on the hill's summit. From here the view across the town, fjord and islands

was truly breath-taking with a panoramic skyline to the south said to encompass

222 peaks (Photo

17 - Varden peak-lined panorama). We did not attempt to count them all but took our photos instead with

the now bright sunlight sparkling across the fjord and dramatic cloud-scape to

enhance the panorama of peaks (see left).

Across Fannefjord

and Langefjord by tunnel, bridge and ferry: beginning the

steep descent into Molde's northern suburbs, we re-joined Route 64 south and

immediately entered the 2.7 km long undersea Fannefjord Tunnel which passes at a

depth of 101m below sea level across to Bolsøya Island in the centre of the

fjord. Completed in 1991 to replace a former ferry, and partially financed by

tolls, the debt was cleared in 14 years and the tunnel became toll-free in 2005.

At the far side of the island, the road curved gracefully over the high-arching

Bolsøy Bridge. Having crossed, we pulled in to view the sweeping bridge from the

fjord-side rocks, with a brisk wind driving breakers onto the shore making an

attractive foreground (see right). We now had a 12kms drive around the western end of the

beautiful Skåla peninsula in the bright afternoon sunshine to catch the next

ferry across Langefjord from Sølsnes to Åfarnes; we made it just in time to drive

straight aboard the ferry which pulled out as we stopped. Across on the far

side, Route 64 hugged the eastern shore of Rødvenfjord which was enclosed on

both sides by pine-forested green fells. In the bright afternoon sunshine with

blue sky reflected in the waters of the fjord, it was a glorious drive. Across Fannefjord

and Langefjord by tunnel, bridge and ferry: beginning the

steep descent into Molde's northern suburbs, we re-joined Route 64 south and

immediately entered the 2.7 km long undersea Fannefjord Tunnel which passes at a

depth of 101m below sea level across to Bolsøya Island in the centre of the

fjord. Completed in 1991 to replace a former ferry, and partially financed by

tolls, the debt was cleared in 14 years and the tunnel became toll-free in 2005.

At the far side of the island, the road curved gracefully over the high-arching

Bolsøy Bridge. Having crossed, we pulled in to view the sweeping bridge from the

fjord-side rocks, with a brisk wind driving breakers onto the shore making an

attractive foreground (see right). We now had a 12kms drive around the western end of the

beautiful Skåla peninsula in the bright afternoon sunshine to catch the next

ferry across Langefjord from Sølsnes to Åfarnes; we made it just in time to drive

straight aboard the ferry which pulled out as we stopped. Across on the far

side, Route 64 hugged the eastern shore of Rødvenfjord which was enclosed on

both sides by pine-forested green fells. In the bright afternoon sunshine with

blue sky reflected in the waters of the fjord, it was a glorious drive.

Rødven stave church: reaching the head of the fjord, we turned off onto

a narrow lane shelving above the fjord's western shore-line. After 10kms through

dairy farming country, we reached the scattered hamlet of Rødven and down by the

fjord we found the tiny wooden Rødven stave-church (Photo

18 - Rødven stave church) (see left). The main body of the tiny

wooden church was built around the early 1300s, perhaps replacing an even

earlier foundation, and was enlarged during the 17th century with some

decorative carvings and wall-paintings added. As at Kvernes, diagonal

side-supports were added at this time after storm damage threatened the church's

structural integrity. Windows were only added in the 19th century. The church

was smaller than Kvernes and lacked the same degree of elaborate wall paintings

and carved wooden works of art; it too had survived the bigotry of the Lutheran

Reformation, but there were none of the evident Catholic features which Kvernes

had managed to retain (Photo

19 - Interior of Rødven stave church). The graveyard ranged up the steep hillside giving a

vantage point from which to photograph the wooden church which glowed in the

afternoon sunlight against the backdrop of high green fells and blue fjord

waters. It was a truly beautiful and peaceful rural setting. Rødven stave church: reaching the head of the fjord, we turned off onto

a narrow lane shelving above the fjord's western shore-line. After 10kms through

dairy farming country, we reached the scattered hamlet of Rødven and down by the

fjord we found the tiny wooden Rødven stave-church (Photo

18 - Rødven stave church) (see left). The main body of the tiny

wooden church was built around the early 1300s, perhaps replacing an even

earlier foundation, and was enlarged during the 17th century with some

decorative carvings and wall-paintings added. As at Kvernes, diagonal

side-supports were added at this time after storm damage threatened the church's

structural integrity. Windows were only added in the 19th century. The church

was smaller than Kvernes and lacked the same degree of elaborate wall paintings

and carved wooden works of art; it too had survived the bigotry of the Lutheran

Reformation, but there were none of the evident Catholic features which Kvernes

had managed to retain (Photo

19 - Interior of Rødven stave church). The graveyard ranged up the steep hillside giving a

vantage point from which to photograph the wooden church which glowed in the

afternoon sunlight against the backdrop of high green fells and blue fjord

waters. It was a truly beautiful and peaceful rural setting.

Around Isfjord to Åndalsnes: returning around the narrow lane to Route

64, we rounded a neck of land into Isfjord where another spectacular mountainous

skyline of serrated peaks opened up to the south, with the port-town of

Åndalsnes visible in the distance on the southern shore of the fjord. But as we

drove along the fjord's northern shore-line, this tranquil setting was scarred

by the intrusive presence of a huge cruise ship anchored in the confines of Isfjord.

We were told later that such cruise ships

regularly befoul Isfjord, overwhelming the tiny

port of Åndalsnes with massed tourists most days of the year. We rounded the head of the inlet at the village of Isfjord and, in heavy

traffic, returned along the south shore into Åndalsnes, eventually finding the

TIC down by the railway station at the terminus of the Raumabanen railway line.

The TIC had closed at 4-00pm but the ticket office was still open for us to

enquire about train times and ticket prices for our planned excursion on the

spectacular line up to Dombås. such cruise ships

regularly befoul Isfjord, overwhelming the tiny

port of Åndalsnes with massed tourists most days of the year. We rounded the head of the inlet at the village of Isfjord and, in heavy

traffic, returned along the south shore into Åndalsnes, eventually finding the

TIC down by the railway station at the terminus of the Raumabanen railway line.

The TIC had closed at 4-00pm but the ticket office was still open for us to

enquire about train times and ticket prices for our planned excursion on the

spectacular line up to Dombås.

Mjelva Camping in Romsdalen: back up

through the town, we turned off onto the E136 up Romsdalen towards Dombås to find

tonight's campsite Mjelva Camping, 6kms from Åndalsnes and set on a high

fell-land shelf overlooking the valley (Photo

20 - Mjelva Camping). We were greeted in a most

friendly and

hospitable manner by the owner who suggested a pitch with breathtaking views

looking up Romsdalen towards the stately skyline of the Trollveggen

range and the

conical peak of Romsdalshornet (Photo

21 - Conical peak of Romsdalshornet). We

settled onto this terrace and enjoyed a relaxing hour sat outside admiring the

surrounding mountainous panorama and the massive rock wall rising up the

mountain-side behind us, as the late train from Dombås trundled down the valley

below our pitch (see above right); this was the perfect spot for our evening barbecue

with the view

looking along

Romsdalen towards the peak-line of Trollveggen

(Photo

22 - Mountain barbecue). The setting sun cast a fluorescent orange glow lighting the

serrated line of peaks up the valley and the horn-shaped peak of Romsdalshornet

(see left),

and tonight darkness really set in with an unbelievably large full-moon rising

above the peaks (see range and the

conical peak of Romsdalshornet (Photo

21 - Conical peak of Romsdalshornet). We

settled onto this terrace and enjoyed a relaxing hour sat outside admiring the

surrounding mountainous panorama and the massive rock wall rising up the

mountain-side behind us, as the late train from Dombås trundled down the valley

below our pitch (see above right); this was the perfect spot for our evening barbecue

with the view

looking along

Romsdalen towards the peak-line of Trollveggen

(Photo

22 - Mountain barbecue). The setting sun cast a fluorescent orange glow lighting the

serrated line of peaks up the valley and the horn-shaped peak of Romsdalshornet

(see left),

and tonight darkness really set in with an unbelievably large full-moon rising

above the peaks (see right).

right).

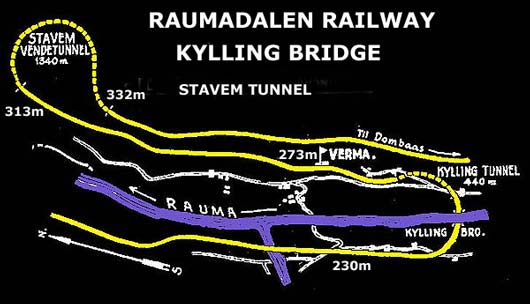

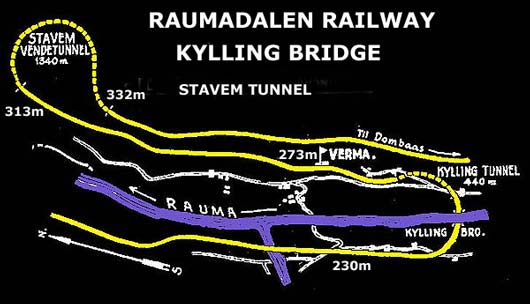

Romsdalen and the Raumabanen railway:

the following morning was overcast, but with an improvement forecast for

later, and a better day tomorrow for our ride on the Raumabanen, our plan for

today was to drive up Romsdalen to view the Trollveggen mountain walls and to

examine the key features of the Raumabanen Railway which enabled the line to

negotiate the higher reaches of the valley. We particularly wanted to photograph

a train passing over the spectacular Kylling Bridge spanning the gorge of the

Romsdal River. After a morning in camp, we set off up Romsdalen, the road and

railway running closely in parallel along the broad, flat-bottomed lower valley.

But 4 kms further, the mountain walls of the mighty Trollveggen range began to

close in totally overshadowing the narrowing valley. In today's overcast

lighting conditions, the mountain walls looked formidably gloomy and lacking in

detail. The now narrow road twisted and turned in the confines of the canyon,

criss-crossing the railway. As the mountain walls which enclosed the lower

valley on both sides opened out, the road began climbing with the river and

railway now running well below us in a wooded gorge.

The Kylling Bridge: gaining much

height, the road reached the hamlet of Verma and just beyond the turning up to

Verma Station, we turned into a parking area by a shop-cum-café near to where

the railway line crosses the river gorge on the high-arching Kylling Bridge. A

footpath was signed to a lookout-point high above the river-gorge looking across

to the stone railway bridge. From the timetable, we could see that the afternoon

down train left Bjorli station some 10 minutes south of here at 2-44pm. With the

weather still gloomily overcast, we The Kylling Bridge: gaining much

height, the road reached the hamlet of Verma and just beyond the turning up to

Verma Station, we turned into a parking area by a shop-cum-café near to where

the railway line crosses the river gorge on the high-arching Kylling Bridge. A

footpath was signed to a lookout-point high above the river-gorge looking across

to the stone railway bridge. From the timetable, we could see that the afternoon

down train left Bjorli station some 10 minutes south of here at 2-44pm. With the

weather still gloomily overcast, we followed the footpath steeply down into

woods to reach a superbly positioned viewing point directly opposite the Kylling

Bridge. This magnificently iconic 76m (249 feet) long bridge, its main stone

arch having a span of 42m (138 feet), rose 59m (194 feet) above the river gorge

and waterfalls way down below (see left). Set among pine woods, this was a truly

magnificent setting; all we needed now was the red railcar of the Raumabanen

train to cross. followed the footpath steeply down into

woods to reach a superbly positioned viewing point directly opposite the Kylling

Bridge. This magnificently iconic 76m (249 feet) long bridge, its main stone

arch having a span of 42m (138 feet), rose 59m (194 feet) above the river gorge

and waterfalls way down below (see left). Set among pine woods, this was a truly

magnificent setting; all we needed now was the red railcar of the Raumabanen

train to cross.

We reached the lookout-point at 2-40pm, taking

trial photos in the gloomy light. Our watches ticked around to 2-44pm when the

train should be leaving Bjorli station, and we stood with cameras poised. With

the line emerging from Kylling Tunnel and hidden by trees immediately before

reaching the bridge-crossing, we should have little warning. The minutes ticked

around as we waited anxiously; had we mis-read the timetable? Then suddenly with

no warning, just after 3-00pm the train reached the bridge, rattling across at

speed without slowing (see above right). Our cameras snapped into action on continuous shoot; in a

flash the train had crossed the bridge and was lost from view

into the trees on the opposite side of the gorge. But we had our photos! (Photo

23 - Kylling Bridge)

Verma Station and the 180º

curving Stavem Tunnel:

after crossing the Kylling Bridge, the railway line enters the 480m long Kylling

Tunnel, curving around through 90º on a gradient to gain further height up to

Verma Station. We walked

back along the road and climbed steeply up a side lane towards the

station with the line high above us. Two monuments stood beside the station: one

was a memorial to the 7 men who were killed during the Raumabanen line's 1912~24

construction; the other memorial bearing the royal coast of arms and Håkon VII's

monogram celebrated the line's official opening on 29 November 1924 (see left). The small

wooden station building by the trackside and passing loop bore the plaque:

Verma 273m høgd over havet (elevation above sea level) - 418,09km Oslo - 39.19 Åndalsnes.

Beyond the station the line curved away northwards towards Stavem Verma Station and the 180º

curving Stavem Tunnel:

after crossing the Kylling Bridge, the railway line enters the 480m long Kylling

Tunnel, curving around through 90º on a gradient to gain further height up to

Verma Station. We walked

back along the road and climbed steeply up a side lane towards the

station with the line high above us. Two monuments stood beside the station: one

was a memorial to the 7 men who were killed during the Raumabanen line's 1912~24

construction; the other memorial bearing the royal coast of arms and Håkon VII's

monogram celebrated the line's official opening on 29 November 1924 (see left). The small

wooden station building by the trackside and passing loop bore the plaque:

Verma 273m høgd over havet (elevation above sea level) - 418,09km Oslo - 39.19 Åndalsnes.

Beyond the station the line curved away northwards towards Stavem Tunnel, more of which later

(see right). The Raumabanen line was truly staggering piece of civil engineering

construction to drive a railway line through such impossibly inhospitable terrain. Tunnel, more of which later

(see right). The Raumabanen line was truly staggering piece of civil engineering

construction to drive a railway line through such impossibly inhospitable terrain.

Further Kylling Bridge photographs:

with the cloud thinning and sun just breaking through (unbelievably as

forecast), we just had enough time to return down the footpath to the

lookout-point for a further photograph of the 3-31pm up

train from Åndalsnes passing over the Kylling Bridge on its way to Dombås. We reached the lookout

at 3-55pm with the train due to reach the intermediate station of Bjorli at

4-15pm. Again we stood with cameras poised, but this time had even less warning

of the train's approach. Hidden by dense trees on the opposite side of the

gorge, the red railcar was there in a flash, but our cameras clicked away as it

sped over the bridge and disappeared into the tunnel. We walked back uphill with

a second set of photos!

The rock faces of Trollveggen:

with a brighter sun now lighting the mountain sides, we drove down from the

upper valley back into the spectacular middle section of Romsdalen where the

mountain walls closed in to create a narrow canyon. On both sides of the road

sheer rock walls towered overhead, those rearing upwards on the eastern side now

fully lit by the afternoon sun. Further down valley however it was the

unbelievable towering rock walls of Trollveggen that really commanded attention.

The ice-smoothed gnarled buttresses rose immediately overhead ominously

threatening in dark shade, then rounding a another bend, sun caught the mountain

side highlighting details on this mighty rock face. It was a truly awe-inspiring

sight (see left). The rock faces of Trollveggen:

with a brighter sun now lighting the mountain sides, we drove down from the

upper valley back into the spectacular middle section of Romsdalen where the

mountain walls closed in to create a narrow canyon. On both sides of the road

sheer rock walls towered overhead, those rearing upwards on the eastern side now

fully lit by the afternoon sun. Further down valley however it was the

unbelievable towering rock walls of Trollveggen that really commanded attention.

The ice-smoothed gnarled buttresses rose immediately overhead ominously

threatening in dark shade, then rounding a another bend, sun caught the mountain

side highlighting details on this mighty rock face. It was a truly awe-inspiring

sight (see left).

We continued into Åndalsnes and parked down at the

port by the railway station (see below right) to buy tickets for our ride on the Raumabanen

tomorrow (Photo

24 - Åndalsnes port). The same helpful lady was on duty at the ticket office: there were no

honnør (senior's) reductions during the summer season on the Åndalsnes~Dombås

tourist trains and the full price of 496 NOK per person would make our two return

fares almost £100! But she suggested a cheaper option: honnør reduced-price regular return tickets for Otta beyond Dombås cost only 316 NOK each; we need

only travel as far as Dombås before catching the return train. Such helpful

advice was much appreciated by us even if not by her employer, the Norwegian

State Railways!

two return

fares almost £100! But she suggested a cheaper option: honnør reduced-price regular return tickets for Otta beyond Dombås cost only 316 NOK each; we need

only travel as far as Dombås before catching the return train. Such helpful

advice was much appreciated by us even if not by her employer, the Norwegian

State Railways!

A ride on the Raumabanen Railway: we were away early the following

morning to be down at Åndalsnes station to catch the 9-27am Raumabanen train.

Visiting cruise ships were not expected until later in the week, but

to our horror the most monstrous of cruise ships was moored by the tiny port,

totally overwhelming the town; this was the embodiment of the very worst kind of

mass tourism, a floating miasma of 3,000 moronic souls milling aimlessly and

disorderly around the port. It was not the last time this trip we should

experience such exploitative invasiveness. The Raumabanen twin railcar was just

pulling into the platform as we arrived, and the guard-conductor shared our

revulsion at the cruise ship's objectionable disturbance at

the little port. Doubtless local businesses rub their greedy hands with glee at

the prospect of the daily invasion of massed ranks of gullible folk anxious to

give money away; not for sure the little community's local residents whose lives

are blighted by the intrusion. The train

pulled away to begin what is promoted as The world's most beautiful train

journey.

Following plans for the Oslo~Trondheim railway

line over Dovrefjell, there was pressure from the coastal municipalities for a

branch line out to the west coast, with intense rivalry between Kristiansund,

Molde and Ålesund as the proposed destination of the line's extension and the

route it would take. By 1910 the National Railway Board proposed a branch line

from Dombås down Romsdalen to Åndalsnes, the Rauma Line, and in 1912 the

Storting gave approval for the line to be built, with the long term aim of

extending it onwards to one of the west coast towns. Construction began in 1912

with navvies working on 4 geographical sections of the route and its

infrastructure. The line was opened in 3 stages: the initial 57kms from Dombås

to Bjorli in late 1921, the next 18kms from Bjorli to Verma in 1923, and the

whole line received its royal opening on 29 November 1924 with regular services Following plans for the Oslo~Trondheim railway

line over Dovrefjell, there was pressure from the coastal municipalities for a

branch line out to the west coast, with intense rivalry between Kristiansund,

Molde and Ålesund as the proposed destination of the line's extension and the

route it would take. By 1910 the National Railway Board proposed a branch line

from Dombås down Romsdalen to Åndalsnes, the Rauma Line, and in 1912 the

Storting gave approval for the line to be built, with the long term aim of

extending it onwards to one of the west coast towns. Construction began in 1912

with navvies working on 4 geographical sections of the route and its

infrastructure. The line was opened in 3 stages: the initial 57kms from Dombås

to Bjorli in late 1921, the next 18kms from Bjorli to Verma in 1923, and the

whole line received its royal opening on 29 November 1924 with regular services starting the following day. The Rauma Line over its 114km length from Dombås,

the line's highest point at 659m above sea level, down to Åndalsnes on the

coastal fjord at 4m above sea level, entails a drop in elevation of 655m. The

nature of the terrain, and achievement of gradients capable of being tackled by

steam locomotives of the day, meant severe challenges for construction engineers.

The line required a total of 103 bridges and 5 tunnels, but it was not just the

problem of spanning gorges with bridges. The greatest challenge was raising the

route up the 655m elevation gain on a satisfactory gradient in upper Romsdalen

(see right). This was achieved by the boldly conceived Stavem

Tunnel, which along its 1,396m length turns through a full 180º on a horseshoe

loop, to emerge further south in the opposite direction with a 19m gain in

elevation from 313m above sea level at its line of entry at the northern end of the tunnel

to 332m at its exit point. The tunnel

took 9 years of hard manual labour to construct and was bored from both ends;

given the 180º curvature and 3 dimensional raising of height, this was an

unbelievable piece of civil engineering (see map above left). But so precise was the surveying that

when the 2 ends joined up, the vertical and horizontal differences were a mere

3.5 cms out! For details of the Raumabanen, see the Norwegian

State Railways web site.

starting the following day. The Rauma Line over its 114km length from Dombås,

the line's highest point at 659m above sea level, down to Åndalsnes on the

coastal fjord at 4m above sea level, entails a drop in elevation of 655m. The

nature of the terrain, and achievement of gradients capable of being tackled by

steam locomotives of the day, meant severe challenges for construction engineers.

The line required a total of 103 bridges and 5 tunnels, but it was not just the

problem of spanning gorges with bridges. The greatest challenge was raising the

route up the 655m elevation gain on a satisfactory gradient in upper Romsdalen

(see right). This was achieved by the boldly conceived Stavem

Tunnel, which along its 1,396m length turns through a full 180º on a horseshoe

loop, to emerge further south in the opposite direction with a 19m gain in

elevation from 313m above sea level at its line of entry at the northern end of the tunnel

to 332m at its exit point. The tunnel

took 9 years of hard manual labour to construct and was bored from both ends;

given the 180º curvature and 3 dimensional raising of height, this was an

unbelievable piece of civil engineering (see map above left). But so precise was the surveying that

when the 2 ends joined up, the vertical and horizontal differences were a mere

3.5 cms out! For details of the Raumabanen, see the Norwegian

State Railways web site.

It was a fine, sunny morning for our journey on

the Raumadalen Railway, and the multilingual commentary described the key

features along the route. In the lower valley the train slowed for passengers to

admire Trollveggen's mighty mountain wall which rose a sheer 1,800m from valley

bottom to its crested pinnacles towering above the railway line which ran past

the foot of the cliffs (Photo

25- Trollveggen from Raumabanen train). The next feature was crossing the Kylling Bridge, which

we had watched from the view-point yesterday. But from the train windows, there

was little impression of the magnificent scale of this beautifully arched stone

bridge. We could only peer down into the gorge 59m below the track. The train

entered the Kylling Tunnel with the line curving through 90º and gaining

height on the steeply rising gradient raising the line up to the higher level of Verma Station. On a continuing rising gradient for a

further km, the line

entered Stavem Tunnel, but from the train there was little sense of the line's

full 180º curve. It was only when the train emerged at the tunnel's southern end

that we could see the line faced in the opposite direction from entering the