|

CAMPING IN SWEDEN 2016 - Småland Kingdom of Glass (Glasriket), Baltic island of Öland,

Kalmar, Southern coastline of Skåne, Kristianstad, Kivik, Ystad, Trelleborg,

Falsterbo sand-spit, Öresund Bridge to Denmark for

journey home: CAMPING IN SWEDEN 2016 - Småland Kingdom of Glass (Glasriket), Baltic island of Öland,

Kalmar, Southern coastline of Skåne, Kristianstad, Kivik, Ystad, Trelleborg,

Falsterbo sand-spit, Öresund Bridge to Denmark for

journey home:

The Småland Glasriket (Kingdom of Glass) and

Målerås Glass Works:

clear skies and warm autumn sunshine for the morning we drove back along the

Oknö peninsula, past the holiday homes and marinas into Mönsterås, to rejoin the

E22 highway. 12 kms south at Ålem we turned off onto a quiet rural lane through

the Småland pine forests (click here for detailed map of route).

The sandy heath-land forest floor was covered with large clumps of

ground-hugging Bearberry with its ripe red berries

(Photo 1 - Ripening Bearberry). This was clearly logging

country judging by the number of timber trucks thundering through these

attractive villages. Reaching Nybro, we made first for the Pukeberg Glassworks,

visited in 2013, hoping today again to witness a demonstration of

glass-blowing. Now however Pukeberg at Nybro was only a glass-making school,

with just one student being taught the skills; to see a glass-working

demonstration, we should need to go to the Målerås glass factory (Glasbruk) 30

kms north up Route 31. A 20 minute drive brought us to the turning into Målerås

village clustered around its surprisingly small glassworks. The Småland Glasriket (Kingdom of Glass) and

Målerås Glass Works:

clear skies and warm autumn sunshine for the morning we drove back along the

Oknö peninsula, past the holiday homes and marinas into Mönsterås, to rejoin the

E22 highway. 12 kms south at Ålem we turned off onto a quiet rural lane through

the Småland pine forests (click here for detailed map of route).

The sandy heath-land forest floor was covered with large clumps of

ground-hugging Bearberry with its ripe red berries

(Photo 1 - Ripening Bearberry). This was clearly logging

country judging by the number of timber trucks thundering through these

attractive villages. Reaching Nybro, we made first for the Pukeberg Glassworks,

visited in 2013, hoping today again to witness a demonstration of

glass-blowing. Now however Pukeberg at Nybro was only a glass-making school,

with just one student being taught the skills; to see a glass-working

demonstration, we should need to go to the Målerås glass factory (Glasbruk) 30

kms north up Route 31. A 20 minute drive brought us to the turning into Målerås

village clustered around its surprisingly small glassworks.

Inside the workshops, we found two

glass-blowers working, and spent an hour watching one of the craftsmen creating

ornate vases and paperweights.

She introduced herself as Marianne Degener who

had herself trained at Målerås in the 1980s; she now had her own studio and

taught glass-making skills to students at the Målerås workshops. It was totally

fascinating watching her take a red hot gobbet of molten glass from the furnace,

slowly work it into shape, then skilfully chop off the finished product into the annealing oven for slow overnight cooling. She readily answered our

questions and demonstrated the technique, explaining the stages of glass-working

(see left and above) (Photo 2 - Glass-blowing at Målerås). She introduced herself as Marianne Degener who

had herself trained at Målerås in the 1980s; she now had her own studio and

taught glass-making skills to students at the Målerås workshops. It was totally

fascinating watching her take a red hot gobbet of molten glass from the furnace,

slowly work it into shape, then skilfully chop off the finished product into the annealing oven for slow overnight cooling. She readily answered our

questions and demonstrated the technique, explaining the stages of glass-working

(see left and above) (Photo 2 - Glass-blowing at Målerås).

|

Click on 2 highlighted areas of

map

for

details of

Southern Sweden |

|

Joelskogens Camping at Nybro:

back into Nybro, we parked by the station to use the public library wi-fi to

check next week's forecast for Öland. After a provisions re-stock at the ICA Kvantum, we drove around to Joelskogens Camping. An earlier phone call had

assured us that, although the reception was closed out of season, keys for the

facilities were available. Despite seemingly situated on a pleasant pine-covered

hillock

alongside the

town lake (see left), the municipal campsite was set in open public

parkland, with local people walking through and children playing down by the

lake, and immediately by a busy main road with the constant noise of passing

traffic. With some misgivings, we settled in but there was scarcely a flat spot

to camp, and as darkness fell the numbers of people still loitering in the open

parkland gave concerns about security. Joelskogens was certainly not a comfortable place

to camp. town lake (see left), the municipal campsite was set in open public

parkland, with local people walking through and children playing down by the

lake, and immediately by a busy main road with the constant noise of passing

traffic. With some misgivings, we settled in but there was scarcely a flat spot

to camp, and as darkness fell the numbers of people still loitering in the open

parkland gave concerns about security. Joelskogens was certainly not a comfortable place

to camp.

Across the bridge to Öland: the following morning, we headed south for the 26kms drive

down to Kalmar, and turned off onto Route 137 to cross the 6kms high-arching

toll-free bridge over the Kalmar Sound to the Baltic island of Öland which was

to be our home for the next 5 days (click here for detailed map of route).

Traffic was busy but we were able to get photos on the downward slope from the

bridge's brow towards the distant shore of Öland

(Photo 3 - Crossing Öland bridge). The slender island is a 120kms long

limestone plateau, scoured by the last Ice Age's retreating ice, leaving a

unique geology and flora. Öland had been a royal hunting ground from the

mid-16th century until 1801, ruled with scant regard for its native peasant

farmers who were barred from chopping wood, hunting animals or selling their

produce on the open market. Danish attacks added to the Ölanders' miseries, and

a series of disastrous harvests in mid-19th century led to a quarter of the

population emigrating to seek a new life in America. Wooden windmills dating

from the 18th century still cover Öland, and as we drove northwards from the

bridge towards the island's main town of Borgholm, we immediately began

to pass classically characteristic features of Öland: conserved post-windmills, dry

limestone walls, and blue chicory flowers at the roadside. scant regard for its native peasant

farmers who were barred from chopping wood, hunting animals or selling their

produce on the open market. Danish attacks added to the Ölanders' miseries, and

a series of disastrous harvests in mid-19th century led to a quarter of the

population emigrating to seek a new life in America. Wooden windmills dating

from the 18th century still cover Öland, and as we drove northwards from the

bridge towards the island's main town of Borgholm, we immediately began

to pass classically characteristic features of Öland: conserved post-windmills, dry

limestone walls, and blue chicory flowers at the roadside.

Borgholm Castle:

the surviving ruins of Borgholm Slott (Castle) were silhouetted on the cliff

tops as we approached the southern outskirts of the town. Construction of the

original fortress was begun in the late 12th century by King Knut Eriksson, and

it had seen much action during 14~16th Swedish~Danish wars. When Gustav Vasa

secured Swedish independence in 1523, he strengthened the huge castle to protect

his new realm, and the castle had enjoyed a brief renaissance as a royal palace

under

the Vasa dynasty. In the mid-17th century Tessin the Elder further

enlarged the royal palace, but by the 18th century the disused castle fell into

ruins, finally being destroyed by fire in 1806. Today the roofless ruins still

stand proudly atop the cliffs near to one of the Swedish royal family's summer

residences, and we walked across the limestone scrubland meadows, where standing

under the stark towers and redoubts showed the castle's fearsome scale (Photo 4 - Borgholm Castle)

(see above right). In

bright afternoon sunshine, we ambled among blackthorn bushes laden with huge sloes, to

the 30m high escarpment which still protects the fortress-palace's seaward side

facing the Kalmar Sound. the Vasa dynasty. In the mid-17th century Tessin the Elder further

enlarged the royal palace, but by the 18th century the disused castle fell into

ruins, finally being destroyed by fire in 1806. Today the roofless ruins still

stand proudly atop the cliffs near to one of the Swedish royal family's summer

residences, and we walked across the limestone scrubland meadows, where standing

under the stark towers and redoubts showed the castle's fearsome scale (Photo 4 - Borgholm Castle)

(see above right). In

bright afternoon sunshine, we ambled among blackthorn bushes laden with huge sloes, to

the 30m high escarpment which still protects the fortress-palace's seaward side

facing the Kalmar Sound.

Blå Rör Bronze Age burial mound:

just north of Borgholm, we turned off to find the late Bronze Age burial mound

of Blå Rör. 40m in diameter and 3m high, the stone-covered tumulus is hidden

away among brambles and scrub-covered sheep pastures behind suburban houses in

the northern outskirts of Borgholm (see left). The cist tomb which the huge cairn covers

had been plundered in antiquity, but archaeological finds at the site date the grave-mound to around 1,000 BC. We took our photos of the burial-mound,

and of the Dewberries growing among brambles, then continued north passing an exposed

section of Öland's classic limestone escarpment. archaeological finds at the site date the grave-mound to around 1,000 BC. We took our photos of the burial-mound,

and of the Dewberries growing among brambles, then continued north passing an exposed

section of Öland's classic limestone escarpment.

Föra medieval church:

we turned off at Vässby to the farming hamlet of Föra. The original church,

built here in the early 11th century soon after Öland's conversion to

Christianity, was a simple wooden stave structure; this was replaced by a more

substantial stone church in the 12th century, and

as times became more

unsettled, with attacks from across the Baltic, the church's tower was fortified

as a defensive refuge. Although the church was extended in later years, this

sturdy west end tower remains, evidence of these violent times (Photo 5 - Föra church).

The church, lit by a bright afternoon sun, was unfortunately locked, but nearby

close to a wooden barn, a large stone cross marked the grave of Martinus (see

right), a

priest killed accidentally in 1431. A tax collecting bailiff, expecting trouble,

thought the steelyard the clergyman was carrying was a weapon; jerking it from

his hand, the bailiff killed him on the spot, which only goes to show that tax

collectors can get away with murder! as times became more

unsettled, with attacks from across the Baltic, the church's tower was fortified

as a defensive refuge. Although the church was extended in later years, this

sturdy west end tower remains, evidence of these violent times (Photo 5 - Föra church).

The church, lit by a bright afternoon sun, was unfortunately locked, but nearby

close to a wooden barn, a large stone cross marked the grave of Martinus (see

right), a

priest killed accidentally in 1431. A tax collecting bailiff, expecting trouble,

thought the steelyard the clergyman was carrying was a weapon; jerking it from

his hand, the bailiff killed him on the spot, which only goes to show that tax

collectors can get away with murder!

Sandvik mill and fishing harbour:

continuing north, we turned off to revisit the huge Dutch windmill at Sandvik.

Unlike the smaller Öland post-mills, where the whole body of the mill is turned

manually into the wind, the larger Dutch mills' sails are fitted to a revolving

cap. The smaller post-mills tended to meet local domestic needs on farms,

whereas the larger Dutch mills were operated as toll mills by a miller, with

payment for grinding farmers' corn either in cash or a share of the grain. The

Sandvik mill was built originally in Småland in 1856; it was sold in 1885 and

transported piecemeal and reassembled here at Sandvik on a 2-storey sandstone

base, and remained in use as a working mill until 1950. It was later converted

to a café, serving traditional Öland peasant meals such as Lufsa and Kroppkakor,

potato dumplings filled with chopped pork and onion. Having photographed the

mill (see above left) (Photo

6 - Sandvik Mill), we moved down to Sandvik's

little fishing harbour where boats were moored at the quays lit by the afternoon

sun (Photo

7 - Sandvik fishing harbour) (see right). on farms,

whereas the larger Dutch mills were operated as toll mills by a miller, with

payment for grinding farmers' corn either in cash or a share of the grain. The

Sandvik mill was built originally in Småland in 1856; it was sold in 1885 and

transported piecemeal and reassembled here at Sandvik on a 2-storey sandstone

base, and remained in use as a working mill until 1950. It was later converted

to a café, serving traditional Öland peasant meals such as Lufsa and Kroppkakor,

potato dumplings filled with chopped pork and onion. Having photographed the

mill (see above left) (Photo

6 - Sandvik Mill), we moved down to Sandvik's

little fishing harbour where boats were moored at the quays lit by the afternoon

sun (Photo

7 - Sandvik fishing harbour) (see right).

Knisa Mosse

Nature Reserve: back

at the main Route 136, a single-track lane led out to the Knisa Mosse Nature

Reserve. These coastal wetlands were spared the 19th century drainage ditching

when as much land as possible on Öland was cultivated to feed a growing

population (see left). The area was used for cutting reeds as roofing material and hay and

for grazing cattle, and conserved as a nature reserve in the mid 20th century

for its birdlife and flora. From the parking area, we followed a faint track through scrubland pastures rather hesitantly past a small herd of large-horned

highland cattle across to an oak copse to the bird observation tower overlooking

the marshes. Low blackthorn bushes full of sloes grew alongside Knisa Mosse

Nature Reserve: back

at the main Route 136, a single-track lane led out to the Knisa Mosse Nature

Reserve. These coastal wetlands were spared the 19th century drainage ditching

when as much land as possible on Öland was cultivated to feed a growing

population (see left). The area was used for cutting reeds as roofing material and hay and

for grazing cattle, and conserved as a nature reserve in the mid 20th century

for its birdlife and flora. From the parking area, we followed a faint track through scrubland pastures rather hesitantly past a small herd of large-horned

highland cattle across to an oak copse to the bird observation tower overlooking

the marshes. Low blackthorn bushes full of sloes grew alongside the path and, crossing

a board-walk we found a patch of

Grass of Parnassus flowers in the moist land (see right); we had seen this

beautiful flower from way up in the Arctic right down to here in the very

south of Scandinavia. The tower overlooked the Knisa Mosse wetlands where ducks

gathered on the waters, gulls flew around and swallows soared overhead dipping

to feed in the shallows the path and, crossing

a board-walk we found a patch of

Grass of Parnassus flowers in the moist land (see right); we had seen this

beautiful flower from way up in the Arctic right down to here in the very

south of Scandinavia. The tower overlooked the Knisa Mosse wetlands where ducks

gathered on the waters, gulls flew around and swallows soared overhead dipping

to feed in the shallows

Wikegårds Camping overlooking the Baltic

shore-line: we returned to the main road and at Hörlösa turned along

the lane, past two post-mills, out to the island's east coast ending at

Wikegårds Farm-Camping. Set on a 19th century croft-farm with the camping areas

spread among the former home pastures, it was a truly delightful place, but

with a tragic history so typical of the desperately hard life endured by Öland's

crofting families, many of whom emigrated: the mother died early and the eldest

daughter brought up her younger siblings while

father worked the farm. The 5

younger children eventually emigrated, and Alma the eldest daughter maintained

the farm until she died in 1959; the farm became a campsite in 1980. As in 2013,

we were again welcomed by the elderly lady owner who chatted away in a

semi-intelligible mix of Swedish and German, showing us the straightforward

facilities and suggesting spots for us to camp. The price was still 200kr/night,

good value for such an exceptional location. We selected a pitch sheltered from

the brisk Öland wind by large juniper bushes, looking out to the magnificent

Baltic shoreline (Photo

8 - Wikegårds Camping) (see left). The evening grew dusky and cool, and as darkness fell, clouds

gathered with only a few stars shining through; in spite of the total absence of

light pollution, there would be no Milky Way tonight, just the twinkling red

lights from a distant array of wind-farms out in the Baltic. It rained heavily

overnight, and the following morning's sky, although bright, was father worked the farm. The 5

younger children eventually emigrated, and Alma the eldest daughter maintained

the farm until she died in 1959; the farm became a campsite in 1980. As in 2013,

we were again welcomed by the elderly lady owner who chatted away in a

semi-intelligible mix of Swedish and German, showing us the straightforward

facilities and suggesting spots for us to camp. The price was still 200kr/night,

good value for such an exceptional location. We selected a pitch sheltered from

the brisk Öland wind by large juniper bushes, looking out to the magnificent

Baltic shoreline (Photo

8 - Wikegårds Camping) (see left). The evening grew dusky and cool, and as darkness fell, clouds

gathered with only a few stars shining through; in spite of the total absence of

light pollution, there would be no Milky Way tonight, just the twinkling red

lights from a distant array of wind-farms out in the Baltic. It rained heavily

overnight, and the following morning's sky, although bright, was overcast for

our day in camp here at Wikegårds. Since our 2013 stay, wi-fi had now been

installed at the farmhouse and the forecast showed improving weather for our

week on Öland. We enjoyed a gloriously peaceful and restful day, and during the

afternoon, the cloud cover broke with a clear warming sun streaming in from

Wikegårds' renowned Big Baltic Sky above the farm's post-mill

(Photo

9 - Wikegårds post-windmill against Big Baltic Sky). overcast for

our day in camp here at Wikegårds. Since our 2013 stay, wi-fi had now been

installed at the farmhouse and the forecast showed improving weather for our

week on Öland. We enjoyed a gloriously peaceful and restful day, and during the

afternoon, the cloud cover broke with a clear warming sun streaming in from

Wikegårds' renowned Big Baltic Sky above the farm's post-mill

(Photo

9 - Wikegårds post-windmill against Big Baltic Sky).

Källa old church and harbour:

returning along the lane the following day, we paused to photograph post-mills

at other farms in the bright morning sunshine (Photo

10 - Öland post-mill) before setting off for our day of

exploration around the North Öland coast (click here for detailed map of route). We turned north at the main road to

the village of Källa to revisit the Gamla Kyrka (old church). The settlement of Källa grew up

around its little harbour.

As attacks from Baltic pirate increased during the

later 12th century, the original 11th century wooden church at Källa was

destroyed by fire, and a new stone church, dedicated to St Olav, was built in

the form of a 2 storey defensive fortress, the church's tower serving as a refuge

in times of attack (see above right). The church was further enlarged in the 14th century and the

tower demolished. A new church was built at Källa in the 19th century as the

village expanded closer to the main road, and most of the old church's fitments

were moved there. The huge barn-like old church with its sturdy stone walls was

conserved as a national heritage, and in 2013 we were able to see its

magnificent interior architecture. Today in September, it was all locked but we

took our photos from the outside from the corner of the graveyard which was

filled with flat-slabbed tombs from the 1600~1700s. Just along from the church,

we reached Källa Hamn at the lane's end; today the little harbour was peaceful

with just a few boats moored by the fishing sheds (see left) (Photo

11 - Källa Hamn). Källa Hamn had once been one of the

busiest harbours along Öland's Baltic coast, with Öland limestone exported from

here for kiln-roasting as fertiliser. As attacks from Baltic pirate increased during the

later 12th century, the original 11th century wooden church at Källa was

destroyed by fire, and a new stone church, dedicated to St Olav, was built in

the form of a 2 storey defensive fortress, the church's tower serving as a refuge

in times of attack (see above right). The church was further enlarged in the 14th century and the

tower demolished. A new church was built at Källa in the 19th century as the

village expanded closer to the main road, and most of the old church's fitments

were moved there. The huge barn-like old church with its sturdy stone walls was

conserved as a national heritage, and in 2013 we were able to see its

magnificent interior architecture. Today in September, it was all locked but we

took our photos from the outside from the corner of the graveyard which was

filled with flat-slabbed tombs from the 1600~1700s. Just along from the church,

we reached Källa Hamn at the lane's end; today the little harbour was peaceful

with just a few boats moored by the fishing sheds (see left) (Photo

11 - Källa Hamn). Källa Hamn had once been one of the

busiest harbours along Öland's Baltic coast, with Öland limestone exported from

here for kiln-roasting as fertiliser.

Neptuni Åkrar beach: we continued north

past the windmills at Högby, and after shopping for provisions at the ICA Nära

at Löttorp village, we turned off beyond Böda around the densely pine-forested

coast road to reach Tokenäs Camping. Just opposite the campsite, a shore-side

post-windmill stood atop a hillock overlooking the Kalmar Sound. The campsite

was virtually empty and we should return there later after our day around the

northern tip of the island. Beyond the little port-resort of Byxelkrok from

where summer ferries cross to Oskarhamn on the mainland, we stopped by the

stony, rubble-field of Neptuni Åkrar, a barren beach of wave-pounded

rubble-banks Neptuni Åkrar beach: we continued north

past the windmills at Högby, and after shopping for provisions at the ICA Nära

at Löttorp village, we turned off beyond Böda around the densely pine-forested

coast road to reach Tokenäs Camping. Just opposite the campsite, a shore-side

post-windmill stood atop a hillock overlooking the Kalmar Sound. The campsite

was virtually empty and we should return there later after our day around the

northern tip of the island. Beyond the little port-resort of Byxelkrok from

where summer ferries cross to Oskarhamn on the mainland, we stopped by the

stony, rubble-field of Neptuni Åkrar, a barren beach of wave-pounded

rubble-banks

above the flat slabs of bed-rock limestone along the waterline. The

flat upper surface of the slabs was scored with linear Orthoceratite fossils, a

marine cephalopod with external tubular shell. Labelled 'Neptune's Fields' by

Linné after his 1741 visit, the 200m wide glacially deposited rubble embankments

have been tiered up by tidal action over aeons, and now presents a barren

appearance stretching for several miles along Öland's NW coastline. Among the

sparse vegetation that somehow manages to take root on the rubble, the

distinctive blue-purple-pink spiky flowers of Viper's Bugloss stand out (see

above right) (Photo

12 - Viper's Bugloss); not a native of Öland, the seeds of this curious plant of the borage family are

thought to have originated in a ship-load of gravel landed at Byxelkrok in the

1930s which in the absence of competition spread along the barren limestone

rubble of the Neptuni Åkrar beach. We walked across the rubble beach expecting

the Viper's Bugloss flowers to be past now, but found enough to be photographed.

Over at the shore-line, the rubble banks sloped steeply down to the mirror-still

waters of Kalmar Sound. The last time we had been here above the flat slabs of bed-rock limestone along the waterline. The

flat upper surface of the slabs was scored with linear Orthoceratite fossils, a

marine cephalopod with external tubular shell. Labelled 'Neptune's Fields' by

Linné after his 1741 visit, the 200m wide glacially deposited rubble embankments

have been tiered up by tidal action over aeons, and now presents a barren

appearance stretching for several miles along Öland's NW coastline. Among the

sparse vegetation that somehow manages to take root on the rubble, the

distinctive blue-purple-pink spiky flowers of Viper's Bugloss stand out (see

above right) (Photo

12 - Viper's Bugloss); not a native of Öland, the seeds of this curious plant of the borage family are

thought to have originated in a ship-load of gravel landed at Byxelkrok in the

1930s which in the absence of competition spread along the barren limestone

rubble of the Neptuni Åkrar beach. We walked across the rubble beach expecting

the Viper's Bugloss flowers to be past now, but found enough to be photographed.

Over at the shore-line, the rubble banks sloped steeply down to the mirror-still

waters of Kalmar Sound. The last time we had been here in 2013, a stiff wind was

driving a pounding surf onto the beach; today there was not a breath of breeze,

and the sun glinted across the still sea with the distant islet of Blå Jungfrau

standing out on the horizon (see left). in 2013, a stiff wind was

driving a pounding surf onto the beach; today there was not a breath of breeze,

and the sun glinted across the still sea with the distant islet of Blå Jungfrau

standing out on the horizon (see left).

Öland's northern tip and Trollskogen Nature

Reserve:

the lane continued around the northern part of the island where this tapered

away to the Norra Udde (Northern Tip), and at the small settlement of Grankulla,

a side-lane turned off onto the eastern

of the 2 peninsulas enclosing Grankullaviken lagoon, ending at the Trollskogen Nature Reserve. Here we set off

to walk the 4.5kms way-marked Trollskogen circuit trail around the forested

Trollskogen peninsula. The path crossed the width of the peninsula, passing a

now fallen ancient oak tree, and running alongside the remains of a stone wall

which once enclosed a medieval royal hunting lodge. The path emerged on the

eastern shore-line which was normally exposed to the full force of gales blowing

across the Baltic. Today however, with virtually no wind, the sky was cloudless

with scarcely a ripple of surf on the shingle beach. It was a picture-postcard

of a view looking along the forest-fringed beach with the still sea reflecting

the blue sky and lit by bright sun

(Photo

13 - Trollskogen beach). We followed the path through

the dark forest alongside the beach looking out through the fringe of trees

towards the sun-lit shore-line (see above right). Some 800m further, we reached the wooden carcass

of the wrecked 3-masted schooner Swiks which foundered here on a stormy

December night in 1926 on its voyage home to Åland from Northern Germany. The

crew managed to get ashore in a lifeboat, and the wreck still lies here on the

stony shore like a beached whale (see left) (Photo

14 - Wreck of schooner Swicks). of the 2 peninsulas enclosing Grankullaviken lagoon, ending at the Trollskogen Nature Reserve. Here we set off

to walk the 4.5kms way-marked Trollskogen circuit trail around the forested

Trollskogen peninsula. The path crossed the width of the peninsula, passing a

now fallen ancient oak tree, and running alongside the remains of a stone wall

which once enclosed a medieval royal hunting lodge. The path emerged on the

eastern shore-line which was normally exposed to the full force of gales blowing

across the Baltic. Today however, with virtually no wind, the sky was cloudless

with scarcely a ripple of surf on the shingle beach. It was a picture-postcard

of a view looking along the forest-fringed beach with the still sea reflecting

the blue sky and lit by bright sun

(Photo

13 - Trollskogen beach). We followed the path through

the dark forest alongside the beach looking out through the fringe of trees

towards the sun-lit shore-line (see above right). Some 800m further, we reached the wooden carcass

of the wrecked 3-masted schooner Swiks which foundered here on a stormy

December night in 1926 on its voyage home to Åland from Northern Germany. The

crew managed to get ashore in a lifeboat, and the wreck still lies here on the

stony shore like a beached whale (see left) (Photo

14 - Wreck of schooner Swicks).

The path turned inland from the beach through

pine woods passing a venerable aged oak said to be 900 year old and still

thriving. Continuing through the forest, parallel with the eastern coastline, we

reached the grove of low pines contorted by exposure to violent gales

blowing in across the Baltic (Photo

15 - Trollskogen contorted pines); the pines' mysteriously twisted shapes

give the name Trollskogen (Trolls' Forest) to the nature reserve. The path

turned inland crossing to the trackway which runs along the spine of the eastern

peninsula; here a short diversion led to a point close to the peninsula's

tip

looking out across the still waters of Grankullaviken lagoon towards the

distant Långe Erik lighthouse on the tip of the western side (see right). The lagoon was almost

enclosed on the seaward side by a chain of islets. The return path wound past

stone defensive works from the 14~16th century wars between Sweden and Denmark,

and Iron Age burial mounds. On the peninsula's more sheltered western side, the

lagoon was fringed with meadows where cattle grazed. The path crossed the

meadows before re-entering the forest, where spotted woodpeckers frolicked high

in the pines, to complete the circuit of the forest nature trail. tip

looking out across the still waters of Grankullaviken lagoon towards the

distant Långe Erik lighthouse on the tip of the western side (see right). The lagoon was almost

enclosed on the seaward side by a chain of islets. The return path wound past

stone defensive works from the 14~16th century wars between Sweden and Denmark,

and Iron Age burial mounds. On the peninsula's more sheltered western side, the

lagoon was fringed with meadows where cattle grazed. The path crossed the

meadows before re-entering the forest, where spotted woodpeckers frolicked high

in the pines, to complete the circuit of the forest nature trail.

Tokenäs Camping: back around the

northern tip of the island through Byxelkrok to Tokenäs Camping, a phone call

brought no response so we settled in at the open area opposite the windmill for

maximum evening sun, with the campsite bathed in golden light. An elderly gent from one of

the static caravans called round to collect our rent; he chatted away jovially

in Swedish too quickly for us to follow, but when he wrote down '65 års', we got

the gist: 'ah rabatt!' we responded - discount for seniors - and paid the

reduced figure of 170kr, very reasonable for such a peaceful setting. As the

golden sun declined and set along the seaward horizon, we dashed over to

photograph the windmill silhouetted against the sunset across

the Kalmar Sound (Photo

16 - Tokenäs post-mill against setting sun) (see above left); it was a glorious spectacle, and later the clear evening

grew dark with a star spangled sky. golden light. An elderly gent from one of

the static caravans called round to collect our rent; he chatted away jovially

in Swedish too quickly for us to follow, but when he wrote down '65 års', we got

the gist: 'ah rabatt!' we responded - discount for seniors - and paid the

reduced figure of 170kr, very reasonable for such a peaceful setting. As the

golden sun declined and set along the seaward horizon, we dashed over to

photograph the windmill silhouetted against the sunset across

the Kalmar Sound (Photo

16 - Tokenäs post-mill against setting sun) (see above left); it was a glorious spectacle, and later the clear evening

grew dark with a star spangled sky.

Byrums Raukar sea stacks: the

overnight cloud cleared to give another clear, sunny day but a fresh northerly

breeze kept temperatures cooler, raising white horses out in the Kalmar Sound.

We packed, re-filled George's fresh water, and set off through Byxelkrok to

pause again at Neptuni Åkrar beach where the brisk wind was today driving a

lively swell off the Sound; the contrast of white waves against the wine-dark

sea this morning made for more interesting photography than yesterday's

flat, glassy calm (see above right). We turned off onto the minor lane around to the northern tip,

and as we drove through the coastal woodland, sea eagles soared overhead and a

kestrel landed on a roadside tree. At the parking area near to Långe Erik

lighthouse, a large flock of cormorants was perched out on the rocks in the Byrums Raukar sea stacks: the

overnight cloud cleared to give another clear, sunny day but a fresh northerly

breeze kept temperatures cooler, raising white horses out in the Kalmar Sound.

We packed, re-filled George's fresh water, and set off through Byxelkrok to

pause again at Neptuni Åkrar beach where the brisk wind was today driving a

lively swell off the Sound; the contrast of white waves against the wine-dark

sea this morning made for more interesting photography than yesterday's

flat, glassy calm (see above right). We turned off onto the minor lane around to the northern tip,

and as we drove through the coastal woodland, sea eagles soared overhead and a

kestrel landed on a roadside tree. At the parking area near to Långe Erik

lighthouse, a large flock of cormorants was perched out on the rocks in the shallows of Grankullaviken lagoon. We walked over to photograph the lighthouse

against the backdrop of breakers driven in by the wind, but cloud had now

gathered giving the scene a grey, dismal air (see left).

shallows of Grankullaviken lagoon. We walked over to photograph the lighthouse

against the backdrop of breakers driven in by the wind, but cloud had now

gathered giving the scene a grey, dismal air (see left).

We drove the circuit of back lanes to re-join

Route 136 down to Böda and turned off to the west coast to re-visit Byrums Raukar

sea stacks. This 600m long stretch of sea stacks, up to 5m in height, has been

carved out of the coastal bed-rock limestone by the erosive action of wind and

waves. At a time 490 million years ago, the land mass of which Öland was then a

part was located in the southern tropics on the bed of a warm, shallow tropical

sea. Limestone deposition built up on the sea bed coral reefs, which under

pressure over aeons formed the Öland limestone. It is estimated that it took

1,000 years of deposition to form a 1mm thickness of limestone;

with today's Öland limestone layers being 40m in depth, this means that it took 40 million

years for the Öland limestone bed-rock to form. Differing content of clay

minerals in the limestone caused variations in its hardness and therefore

resistance to erosion. At Byrums, softer limestone has been eroded by wind and

wave action, leaving behind the stacks of harder, more resistant limestone. We

parked at the end of road shore-side and walked along to the first of the Byrums

stacks. The cloud cover of earlier was just beginning to break, and the sky

clearing to give bright western sun, perfect lighting conditions for

photographing the line of sea-stacks against the dark sea and white waves

breaking against the foot of the limestone cliffs, continuing with today's Öland limestone layers being 40m in depth, this means that it took 40 million

years for the Öland limestone bed-rock to form. Differing content of clay

minerals in the limestone caused variations in its hardness and therefore

resistance to erosion. At Byrums, softer limestone has been eroded by wind and

wave action, leaving behind the stacks of harder, more resistant limestone. We

parked at the end of road shore-side and walked along to the first of the Byrums

stacks. The cloud cover of earlier was just beginning to break, and the sky

clearing to give bright western sun, perfect lighting conditions for

photographing the line of sea-stacks against the dark sea and white waves

breaking against the foot of the limestone cliffs, continuing their erosive

action (see above right) (Photo

17 - Byrums Raukar sea stacks). The grey knobbly limestone surface

crumbled into pebble-sized chunks to reveal fossils of the creatures

whose exoskeletons formed the limestone. We clambered from one stack's top to

the next, and down into the mini-canyons between the stacks to the water's edge (Photo

18 - Byrums Raukar sea stacks).

In such perfect conditions, particularly looking westwards with the light

silhouetting the line of stacks and adding sparkle to the waves washing onto the

base of the cliffs, the hour spent at Byrums was another of the trip's memorable

highlights (see above left) . their erosive

action (see above right) (Photo

17 - Byrums Raukar sea stacks). The grey knobbly limestone surface

crumbled into pebble-sized chunks to reveal fossils of the creatures

whose exoskeletons formed the limestone. We clambered from one stack's top to

the next, and down into the mini-canyons between the stacks to the water's edge (Photo

18 - Byrums Raukar sea stacks).

In such perfect conditions, particularly looking westwards with the light

silhouetting the line of stacks and adding sparkle to the waves washing onto the

base of the cliffs, the hour spent at Byrums was another of the trip's memorable

highlights (see above left) .

We returned to Tokenäs Camping for a third

night; it was good value and peaceful, and with the sky still clear, we could

enjoy another sunset behind the windmill. Early evening, the elderly gent came

round again to collect tonight's rent, chatting away in rapid

Swedish with us

catching just the occasional word. Tonight, apart from his caravan as the only

other occupant, we had the campsite to ourselves, and the sun set across the

Sound once more silhouetting the windmill against a crimson sky (see above right). Swedish with us

catching just the occasional word. Tonight, apart from his caravan as the only

other occupant, we had the campsite to ourselves, and the sun set across the

Sound once more silhouetting the windmill against a crimson sky (see above right).

Eastern coast road and Gärdslösa medieval

church: after a

chill night, a dewy autumnal start to the day with clear sun rising

over the tall trees behind our camping spot. This time of year, Tokenäs Camping

had served us well, but only early or late in the season could peacefulness be

assured. Today we should travel the full 120kms length of the island from its

northern tip to explore Southern Öland. For the return drive to Borgholm, we

took the eastern coast road passing marshland and farming countryside, and after

a provisions

restock

at Borgholm, we were ready to begin our exploration of Southern Öland (click here for detailed map of route).

Crossing the island's width past wealthy-looking farmsteads, we reached the east

coast and close to the hamlet of Störlinge, paused to photograph a line of 7

post-mills set along a roadside embankment (see above left). A further km south, we reached the

village of Gärdslösa to visit the wonderfully preserved medieval stone church,

built in the 12th century to replace an earlier wooden church. After photos from

under the trees in the lovingly maintained graveyard (Photo

19 - Gärdslösa medieval church), we admired

the interior with

its 16th century frescoes and beautifully decorative pulpit carved by 17th

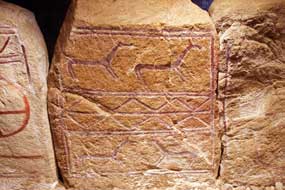

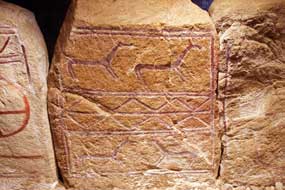

century Kalmar craftsmen (see right). In the south transept, a runic graffito has been

exposed in the plasterwork, which translates as Johan made me. All along

this road, farmsteads showed their medieval layout of a series of wooden barns

running linearly along the roadside with one gateway into an enclosed courtyard

with farmhouse and gardens. restock

at Borgholm, we were ready to begin our exploration of Southern Öland (click here for detailed map of route).

Crossing the island's width past wealthy-looking farmsteads, we reached the east

coast and close to the hamlet of Störlinge, paused to photograph a line of 7

post-mills set along a roadside embankment (see above left). A further km south, we reached the

village of Gärdslösa to visit the wonderfully preserved medieval stone church,

built in the 12th century to replace an earlier wooden church. After photos from

under the trees in the lovingly maintained graveyard (Photo

19 - Gärdslösa medieval church), we admired

the interior with

its 16th century frescoes and beautifully decorative pulpit carved by 17th

century Kalmar craftsmen (see right). In the south transept, a runic graffito has been

exposed in the plasterwork, which translates as Johan made me. All along

this road, farmsteads showed their medieval layout of a series of wooden barns

running linearly along the roadside with one gateway into an enclosed courtyard

with farmhouse and gardens.

Ismantorp Iron Age ring-fortress: turning inland at Långlöt, and

passing the post-mills by the Himmelsberga skansen, we took a side-lane ending

at the parking area for Ismantorp Early Iron Age ring-fortress. The oldest of

the 20 known ring-forts on Öland and built around 200 AD, the circular limestone

block-built exterior wall, remarkably conserved at 3~4m in height, encloses an

open inner space with the stone foundation-remains of 95 dwellings (see left). Excavations

at the site have revealed no archaeological remains, and the fortress was likely

not to have been permanently occupied. It is thought to have been the fortified

headquarters for a clan chieftain and his garrison who controlled the

surrounding area, and a secure refuge for his peasant Ismantorp Iron Age ring-fortress: turning inland at Långlöt, and

passing the post-mills by the Himmelsberga skansen, we took a side-lane ending

at the parking area for Ismantorp Early Iron Age ring-fortress. The oldest of

the 20 known ring-forts on Öland and built around 200 AD, the circular limestone

block-built exterior wall, remarkably conserved at 3~4m in height, encloses an

open inner space with the stone foundation-remains of 95 dwellings (see left). Excavations

at the site have revealed no archaeological remains, and the fortress was likely

not to have been permanently occupied. It is thought to have been the fortified

headquarters for a clan chieftain and his garrison who controlled the

surrounding area, and a secure refuge for his peasant farmers in times of

danger. Nothing is known for certain about the ring-fort's history or its

occupants, but it was abandoned around 650 AD. But the scale and solidity of the

fortress' construction to have lasted so well is an indication of the power of

the chieftain who controlled Ismantorp. farmers in times of

danger. Nothing is known for certain about the ring-fort's history or its

occupants, but it was abandoned around 650 AD. But the scale and solidity of the

fortress' construction to have lasted so well is an indication of the power of

the chieftain who controlled Ismantorp.

The approach on foot to Ismantorp adds to the

mystique of the place: from the parking area, a winding path leads for 200m

through a dark wood, suddenly opening into a wide meadow with the fortified

village's stone walls in the centre. It is as if you have passed through a

portal into a lost bygone age. Across to one of the 9 gates through the 4m high

perimeter wall, we entered the central protected area with its layout of stone

foundation-remains of dwellings. Clambering up onto the wall top gave a full

overview both of the extent of the enclosed area of dwellings, the

solidity of the circuit-walls' construction, and the remarkable state of its

preservation which had survived for 1,800 years

(Photo

20 - Ismantorp Iron Age ring-fortress). With no other sound

but the wind in the trees of the surrounding forests, Ismantorp is indeed a

mystical place; one could only speculate about the power exercised by the

chieftains, the lives of their clansmen, how often

they had to take refuge in

the fortress, and the nature of the external threats they faced. Standing here in

the fortress' inner area among the ruins of dwellings, in the silence of Ismantorp's lost world, was another of the trip's memorable highlights. they had to take refuge in

the fortress, and the nature of the external threats they faced. Standing here in

the fortress' inner area among the ruins of dwellings, in the silence of Ismantorp's lost world, was another of the trip's memorable highlights.

Gråborg Iron Age~Medieval ring-fortress: we continued south along

the eastern coast road passing an area of Iron Age grave-fields and another line

of post-mills at Lerkaka with a modern-day harvester standing behind them at a

farm. At the aptly named hamlet of Runsten, the

eponymous runestone with ornately carved inscription stood by the roadside. At Norra Möckleby we again turned

inland to find the Gråborg Iron Age~Medieval

ring-fortress. The approach pathway passed by a classic Öland farmstead with

long-barn enclosing its farmhouse courtyard. Gråborg is an even bigger ring-fort

built in the 6th century AD at a time when Ismantorp was in decline. It was

later adapted with strengthened walls as a military fortification and trade

centre in medieval times, and was even occupied as defence against Danish attacks

as late as the 17th century. Nothing of the Iron Age fortified settlement or

later medieval military works survives today other than the 7m high ring-walls

(see above left)

and a vaulted medieval gateway (see right); the vast open space enclosed by the circular walls

is now meadowland mown for hay. Nearby stand the remains of the medieval chapel

of St Knut and tax records show both the fortress and chapel were owned by Vadstena Abbey

(Photo

21 - St Knut's Chapel). We took our photos and continued our drive down the eastern

coast road passing more windmills and grave-fields. inland to find the Gråborg Iron Age~Medieval

ring-fortress. The approach pathway passed by a classic Öland farmstead with

long-barn enclosing its farmhouse courtyard. Gråborg is an even bigger ring-fort

built in the 6th century AD at a time when Ismantorp was in decline. It was

later adapted with strengthened walls as a military fortification and trade

centre in medieval times, and was even occupied as defence against Danish attacks

as late as the 17th century. Nothing of the Iron Age fortified settlement or

later medieval military works survives today other than the 7m high ring-walls

(see above left)

and a vaulted medieval gateway (see right); the vast open space enclosed by the circular walls

is now meadowland mown for hay. Nearby stand the remains of the medieval chapel

of St Knut and tax records show both the fortress and chapel were owned by Vadstena Abbey

(Photo

21 - St Knut's Chapel). We took our photos and continued our drive down the eastern

coast road passing more windmills and grave-fields.

Southern Öland's Stora Alvaret limestone

plateau: at Brunneby we turned off inland to cross the semi-barren

limestone plateau of Stora Alvaret, the vast limestone plateau which

covers the bulk of Southern Öland; at 260km2 it is the largest such

limestone expanse in Europe. Southern Öland's topography showed the nature of

the island's agriculture, with the coastal strip having the most fertile, deeper

soil, cultivated as arable land and meadows, and the inland Alvar plain

with its thin soil mantle and sparse vegetation grazed by cattle and sheep. The

medieval layout of farmsteads along the line of the coastal strip, and frequency

of Iron Age grave-fields and medieval churches, show these lands to have had

continuity of human occupation for almost 2,000 years. And the number of farm

vehicles passing along the coast road, and affluence of modern farmsteads,

showed that agriculture still flourished. Southern Öland's Stora Alvaret limestone

plateau: at Brunneby we turned off inland to cross the semi-barren

limestone plateau of Stora Alvaret, the vast limestone plateau which

covers the bulk of Southern Öland; at 260km2 it is the largest such

limestone expanse in Europe. Southern Öland's topography showed the nature of

the island's agriculture, with the coastal strip having the most fertile, deeper

soil, cultivated as arable land and meadows, and the inland Alvar plain

with its thin soil mantle and sparse vegetation grazed by cattle and sheep. The

medieval layout of farmsteads along the line of the coastal strip, and frequency

of Iron Age grave-fields and medieval churches, show these lands to have had

continuity of human occupation for almost 2,000 years. And the number of farm

vehicles passing along the coast road, and affluence of modern farmsteads,

showed that agriculture still flourished.

We turned off across the flat, barren waste of

the Alvar, initially passing stunted trees and then the extensive open,

featureless plain stretching away to the horizon on both sides of the road (see

left and right). The

Alvar plain had been formed following the last Ice Age when retreating

glaciers had scoured the bed-rock limestone of what became Öland as the land

rose from the Baltic, relieved of the weight of ice. Animal and human life

populated the island, migrating across the residual ice-bridge from the

mainland. Over the next millennia, the bare limestone was overlaid by a thin

mantle of soil, only 2cms at its thickest, by plant colonisation and wind-driven

deposition to create the alvar formation seen today. The term alvar

is derived from this thin soil covering and in some places the limestone

bed-rock still shows through with with no soil covering at all. During the Bronze

and Iron Ages, farming developed on the Alvar which was used to graze

animals, but in the 18~19th centuries over-exploitation of the poor soil caused

even further denuding of the surface vegetation; with insufficient arable land

to feed an increasing population, many emigrated to escape starvation and seek a

new life overseas leaving abandoned villages like Dröstorp. Driving across the

Alvar plain, we stopped a couple of times to photograph this deserted

wilderness, today criss-crossed by dry-stone walls and with just a few livestock

grazing (Photo

22 - Stora Alvaret limestone plateau).

Resmo medieval church and the 10th century

Karlevi Runestone:

at the far end of the road across the Alvar, we reached Resmo village and

paused to photograph the 11th century church, said to be Öland's oldest

surviving church still in regular use (see left). It began as a private foundation Resmo medieval church and the 10th century

Karlevi Runestone:

at the far end of the road across the Alvar, we reached Resmo village and

paused to photograph the 11th century church, said to be Öland's oldest

surviving church still in regular use (see left). It began as a private foundation in the

11th century, endowed by a local wealthy landowner who stood to gain from his

investment in the church from fees paid by parishioners for baptisms, weddings

and funerals. Again the tower was strengthened as a defensive refuge, but the

Danish invasions of 1677 wrought havoc with the decorations, treasures and

archives of both Resmo and Vickleby churches plundered or destroyed. We turned

down the steep slope of Öland's western coastal escarpment to revisit the

Karlevi runestone set amid fields down by the Kalmar Sound. Dated to the late

10th century, the time of transition from the pagan Æsir religion to

Christianity, the runestone is unique in containing within its runic inscription

both the prose dedication to a Viking chieftain and the oldest known stanza of

Skaldic verse, and on the reverse side a later non-runic inscription with

Christian reference. The stone marks the grave of the Danish chieftain Sibbi

Fuldarsson, killed in the 985 AD battle of Fýrisvellir, and was raised in dedicatory memory by his retinue. The prose

dedication records the commemoration to Sibbi, and the honorific verse which

follows mentions a female Valkyrie deity Thrud and reference to one of the names

of Odin, perhaps an acknowledgement that Sibbi still clung to the old pagan

beliefs. The 1.4m high, rounded top stone was not Öland limestone, but harder

granite rock transported from elsewhere. The main inscription was deeply

engraved in beautiful runic characters in vertical lines covering the front face

and in the

11th century, endowed by a local wealthy landowner who stood to gain from his

investment in the church from fees paid by parishioners for baptisms, weddings

and funerals. Again the tower was strengthened as a defensive refuge, but the

Danish invasions of 1677 wrought havoc with the decorations, treasures and

archives of both Resmo and Vickleby churches plundered or destroyed. We turned

down the steep slope of Öland's western coastal escarpment to revisit the

Karlevi runestone set amid fields down by the Kalmar Sound. Dated to the late

10th century, the time of transition from the pagan Æsir religion to

Christianity, the runestone is unique in containing within its runic inscription

both the prose dedication to a Viking chieftain and the oldest known stanza of

Skaldic verse, and on the reverse side a later non-runic inscription with

Christian reference. The stone marks the grave of the Danish chieftain Sibbi

Fuldarsson, killed in the 985 AD battle of Fýrisvellir, and was raised in dedicatory memory by his retinue. The prose

dedication records the commemoration to Sibbi, and the honorific verse which

follows mentions a female Valkyrie deity Thrud and reference to one of the names

of Odin, perhaps an acknowledgement that Sibbi still clung to the old pagan

beliefs. The 1.4m high, rounded top stone was not Öland limestone, but harder

granite rock transported from elsewhere. The main inscription was deeply

engraved in beautiful runic characters in vertical lines covering the front face

and

side (see right), while on the reverse face were Christian characters in Roman script,

interpreted as In Nomin[e]...Ie[su], raising the question whether this

was contemporary

with the runic inscription almost as a 'fail-safe' addendum at

time of religious transition or a later Christian defamatory graffito on a pagan

monument. Either way, our feeling was that the Karlevi monument, along with the

Rök runestone, was the most intriguing of those we had seen, a very special

monument marking the final resting place of a Viking warrior-chieftain (Photo

23 - Karlevi Runestone). side (see right), while on the reverse face were Christian characters in Roman script,

interpreted as In Nomin[e]...Ie[su], raising the question whether this

was contemporary

with the runic inscription almost as a 'fail-safe' addendum at

time of religious transition or a later Christian defamatory graffito on a pagan

monument. Either way, our feeling was that the Karlevi monument, along with the

Rök runestone, was the most intriguing of those we had seen, a very special

monument marking the final resting place of a Viking warrior-chieftain (Photo

23 - Karlevi Runestone).

A

peaceful night's camp at Gräsgårds Fiskehamn: returning through

Vickleby, we re-crossed the width of the Alvar plain on another lane,

taking us back to the east coast. It was by now 5-30pm and the low sun cast a

golden light over the grave-fields at Segestad. We paused to photograph the 3m

high 11th century runestone by the road side at Seby (see left); the runic inscription

enclosed within scrolls translates as Ingjald, Näf and Sven erected this

stone as a memorial to their father Rodmar. The face of the limestone showed

traces of exposed Orthoceratite fossils between the lines of runes. We were

weary after a long day of exploration, and looking forward to camping again by

the fishing harbour of Gräsgårds

Hamn where we had enjoyed a peaceful stay in

2103. To our relief, the straightforward little campsite at the end of the lane

by the tiny port was not only still open but empty. The small camping area

enclosed by a ring of dilapidated huts was unchanged, as if frozen in a

time-warp, with its basic facilities and power supplies covered by a plastic

fish crate. The instructions to leave the nightly charge of 110kr (unchanged

since 2013) in an envelope at the reception hut was still there, and with the

sun declining and the dusky evening growing cool, we gladly settled in with

George's nose into the crisp breeze blowing in from the Baltic and the open

slider facing out to the fishing harbour. The sun set leaving a deep salmon glow

along the western horizon, and the evening grew dark with a thin sliver of new

moon rising over the Baltic. What a thoroughly fulsome day this had been, and

how good it was to be camping again at this wonderfully peaceful setting on the

Baltic coastline here at Gräsgårds Fiskehamn. runestone by the road side at Seby (see left); the runic inscription

enclosed within scrolls translates as Ingjald, Näf and Sven erected this

stone as a memorial to their father Rodmar. The face of the limestone showed

traces of exposed Orthoceratite fossils between the lines of runes. We were

weary after a long day of exploration, and looking forward to camping again by

the fishing harbour of Gräsgårds

Hamn where we had enjoyed a peaceful stay in

2103. To our relief, the straightforward little campsite at the end of the lane

by the tiny port was not only still open but empty. The small camping area

enclosed by a ring of dilapidated huts was unchanged, as if frozen in a

time-warp, with its basic facilities and power supplies covered by a plastic

fish crate. The instructions to leave the nightly charge of 110kr (unchanged

since 2013) in an envelope at the reception hut was still there, and with the

sun declining and the dusky evening growing cool, we gladly settled in with

George's nose into the crisp breeze blowing in from the Baltic and the open

slider facing out to the fishing harbour. The sun set leaving a deep salmon glow

along the western horizon, and the evening grew dark with a thin sliver of new

moon rising over the Baltic. What a thoroughly fulsome day this had been, and

how good it was to be camping again at this wonderfully peaceful setting on the

Baltic coastline here at Gräsgårds Fiskehamn.

We woke the following morning to an overcast

sky with just a band of brighter light along the eastern horizon. This clearer

sky gradually spread, so that by breakfast time we could sit outside in bright,

warm sunshine (see above right) (Photo

24 - Gräsgårds Fiskehamn Camping). Before leaving Gräsgårds, we walked over to

the little fishing harbour where fewer working boats were moored than 3 years ago

on our first stay; it looked as if fishing was in decline. The boats had just

returned from their morning's work (we had seen their navigation lights as they

had set out earlier at 4-00am), but the fishermen were carrying just one iced

box of fish over to the sheds; no wonder it was a declining industry. We wished

one of them Tack för camping as he sat repairing nets on an ancient

sewing machine at one of the huts; Var så god (You're welcome) was his terse response. Photographing the boats was a lovely

conclusion to our say once more at Gräsgårds Fiskehamn, but if we ever return,

how many boats will be left, we wondered (Photo

25- Gräsgårds fishing boats) (see left).

Seby

prehistoric grave-fields:

before heading down to Ottenby and the Södre Udde (Southernmost Point) of Öland,

we diverted briefly north to the Iron Age grave-fields at Seby and Segestad. The

line of Öland's south-eastern coastal road is marked by a narrow, low-lying

ridge, originally a raised beach formed as land levels rose following the last

Ice Age. The fertile soil along this ridge has been farmed and grazed for over

2,000 years of occupation, with farms and villages developing along the line of

the ridge from the early Iron Age, through Viking and medieval times, up to the

present day. Evidence for this continuity of human occupation can be Seby

prehistoric grave-fields:

before heading down to Ottenby and the Södre Udde (Southernmost Point) of Öland,

we diverted briefly north to the Iron Age grave-fields at Seby and Segestad. The

line of Öland's south-eastern coastal road is marked by a narrow, low-lying

ridge, originally a raised beach formed as land levels rose following the last

Ice Age. The fertile soil along this ridge has been farmed and grazed for over

2,000 years of occupation, with farms and villages developing along the line of

the ridge from the early Iron Age, through Viking and medieval times, up to the

present day. Evidence for this continuity of human occupation can be

traced not

only from the farmsteads and villages along the line of the road; the ridge was

also the only place with soil deep enough for human burials, and at Seby and

Segestad, some 285 stone grave monuments have been found dating from the early

Iron Age (200 AD) to the Viking period (1,000 AD), when with conversion to

Christianity and building of churches, burials transferred to churchyards. Just

outside Segestad, some of the most prominent standing stone monoliths stood

along the line of the ridge, and opposite to the east of the road, the coastal

strip of farmland stretched away to the Baltic shore grazed by modern cattle.

Taken together, ancient standing stones marking burials and modern farming symbolised this long

continuity of human occupation. traced not

only from the farmsteads and villages along the line of the road; the ridge was

also the only place with soil deep enough for human burials, and at Seby and

Segestad, some 285 stone grave monuments have been found dating from the early

Iron Age (200 AD) to the Viking period (1,000 AD), when with conversion to

Christianity and building of churches, burials transferred to churchyards. Just

outside Segestad, some of the most prominent standing stone monoliths stood

along the line of the ridge, and opposite to the east of the road, the coastal

strip of farmland stretched away to the Baltic shore grazed by modern cattle.

Taken together, ancient standing stones marking burials and modern farming symbolised this long

continuity of human occupation.

Ottenby

bird reserve at Öland's southernmost

tip: heading south to Ottenby, we turned off along the single-track

lane leading across the treeless Alvar fields, the tail end of Southern Öland's

limestone plateau, once a royal hunting reserve and now grazed by sheep and

cattle, to the Långe Jan lighthouse at Öland's southernmost tip. we parked by

the bird observation station and sat to eat our sandwich lunch, entertained by

the silly antics of tourists milling around. Armed with cameras, tripod and

binoculars, we walked over past the sturdy lighthouse tower out to the shore-side

bird-watching area (Photo

26- Bird-watching at Ottenby). A hazy sun shone brightly, but today a brisk NW wind blowing

across the Sound ruffled the water's surface. Sea levels seemed higher than on

our last visit with fewer rocks visible off-shore. From the water's edge we

could see a number of mute swans gliding around just off-shore and a large flock

of cormorants lighthouse at Öland's southernmost tip. we parked by

the bird observation station and sat to eat our sandwich lunch, entertained by

the silly antics of tourists milling around. Armed with cameras, tripod and

binoculars, we walked over past the sturdy lighthouse tower out to the shore-side

bird-watching area (Photo

26- Bird-watching at Ottenby). A hazy sun shone brightly, but today a brisk NW wind blowing

across the Sound ruffled the water's surface. Sea levels seemed higher than on

our last visit with fewer rocks visible off-shore. From the water's edge we

could see a number of mute swans gliding around just off-shore and a large flock

of cormorants

perched on rocks or

flying around (Photo

27 - Cormorants in flight). Over to the western side, many eider ducks

and goosanders (see right) sat at the water's edge or swam in the shallows. The

eiders' black and white plumage made them well camouflaged on the

pebbly shore (see above left). Further over, lines of cormorants stood in rows or flew off in

flocks, but with a brisk wind blowing and sea levels higher leaving no exposed

rocks, there were no Grey or Harbour Seals to be seen as on our 2013 visit. perched on rocks or

flying around (Photo

27 - Cormorants in flight). Over to the western side, many eider ducks

and goosanders (see right) sat at the water's edge or swam in the shallows. The

eiders' black and white plumage made them well camouflaged on the

pebbly shore (see above left). Further over, lines of cormorants stood in rows or flew off in

flocks, but with a brisk wind blowing and sea levels higher leaving no exposed

rocks, there were no Grey or Harbour Seals to be seen as on our 2013 visit.

We spent time watching and photographing the

birds, but disappointed by the apparent absence of seals, we walked back past

the lighthouse (see below right) to the

Visitor Centre to enquire further. The warden explained that with the strong

wind blowing from the NW and sea levels higher, all the seals tended to gather

further round on the more sheltered eastern side of the cape where there were more exposed

rocks for them to bask on. She advised us on a viewing hide which gave a distant

but unimpeded view of the basking seals. Bulky, hump-backed Harbour Seals,

looking like huge, glossy black slugs basked on the prominent rocks just

off-shore, with smaller, sleek Grey Seals wallowing in the shallows. We

positioned the tripod and spent a happy hour watching this colony of seals through binoculars and photographing them at extreme telephoto range

(Photo

28 - Grey- and Harbour-Seals) (see above left).

binoculars and photographing them at extreme telephoto range

(Photo

28 - Grey- and Harbour-Seals) (see above left).

Öland's south-western coast and Gettlinge

prehistoric burial grounds: further back from the Ottenby bird reserve

at the lighthouse, we walked over to another early Iron Age burial ground marked

by 2 huge monoliths, the Kungsstenarna (King's Stones) (see below left), the southernmost of the

prehistoric grave-fields which extend along the length of Öland's southern tip.

It was now time to leave Ottenby to begin the return drive north up the island's

western coastal road overlooking the Kalmar Sound (click here for detailed map of route).

But by now the best of today's sun was gone and cloud gathering. We had several

possible camping options identified for tonight and would investigate these on

our way up to the Gettlinge grave-fields. The first was a ställplats by

the marina at Grönhögens Hamn, a wide, formally laid out, grassy camping aire

with full facilities, but the uncongenial company of camping-cars already parked

there was sufficient of a deterrent. We moved on to Ventlinge, a small village a

couple of miles up the coast where we had found reference to a small campsite opposite the church.

Driving through the village, sure enough there was the

sign pointing to a camping

area in a large garden behind a cottage; this looked

ideal for this evening, particularly as it was uncontaminated by camping-cars. area in a large garden behind a cottage; this looked

ideal for this evening, particularly as it was uncontaminated by camping-cars.

For now we continued north with the road following

the line of the low western coastal ridge of fertile ground with good depth of

soil, sandwiched between the coastal Sound to the west and the bare, infertile Alvar

limestone plateau inland to the east. At Degerhamn we turned down into the

village, surprised at how steeply the land dropped away via hair-pins to

negotiate a tiered escarpment of former raised beaches down to the modern

shore-line. Degerhamn's origins were instantly evident from the huge cement

works befouling the little port: clearly Öland limestone had been ground and

roasted into cement here for export from the harbour. The ställplats at

Degerhamn had been another of our camping options, but its neglected air and

perfect view of the cement works ruled it out!

We continued along the main road to Gettlinge; the

sky was now disappointingly overcast with a gloomy light for photographing the

impressive grave-fields. As on the Baltic coastline, there had been a continuum

of human occupation along this western coastal ridge since the Bronze Age,

through the Iron Age, Viking and Medieval times, right down to the

present, with farms, villages, burial grounds, churches and graveyards spread

along the narrow coastal strip and animals grazed on the Alvar plain

inland. The low ridge, produced originally by wave action on the residue of a

raised beach formed during the post-glacial land uplift, created a deeper layer

of fertile moraine soil along the line of the ridge than the thinner surface

layer inland across the Alvar. This deeper soil layer, running north~south between the coastal strip and western fringe of the Stora Alvaret

limestone plateau, provided the only hospitable place for dwellings, for

farming, and for burial of the dead. Both villages and grave-fields therefore

spread along the length of the ridge from over 2,000 years of human occupation.

As the land-uplift has continued over aeons, the line of the ancient ridge now

stands high above the modern shore-line which is now at the foot of a steeply

sloping escarpment. What remarkable topography Southern Öland displays. One

of the island's largest prehistoric burial grounds extends for some 2 kms along

this ridge at Gettlinge, covering the period from 1,000 BC to 1,000 AD, with

Bronze Age burial mounds, Iron Age standing stones, and stone ship-settings from

the Viking period. Just south of the modern village, we reached the most

prominent grave fields We continued along the main road to Gettlinge; the

sky was now disappointingly overcast with a gloomy light for photographing the

impressive grave-fields. As on the Baltic coastline, there had been a continuum

of human occupation along this western coastal ridge since the Bronze Age,

through the Iron Age, Viking and Medieval times, right down to the

present, with farms, villages, burial grounds, churches and graveyards spread

along the narrow coastal strip and animals grazed on the Alvar plain

inland. The low ridge, produced originally by wave action on the residue of a

raised beach formed during the post-glacial land uplift, created a deeper layer

of fertile moraine soil along the line of the ridge than the thinner surface

layer inland across the Alvar. This deeper soil layer, running north~south between the coastal strip and western fringe of the Stora Alvaret

limestone plateau, provided the only hospitable place for dwellings, for

farming, and for burial of the dead. Both villages and grave-fields therefore

spread along the length of the ridge from over 2,000 years of human occupation.

As the land-uplift has continued over aeons, the line of the ancient ridge now

stands high above the modern shore-line which is now at the foot of a steeply

sloping escarpment. What remarkable topography Southern Öland displays. One

of the island's largest prehistoric burial grounds extends for some 2 kms along

this ridge at Gettlinge, covering the period from 1,000 BC to 1,000 AD, with

Bronze Age burial mounds, Iron Age standing stones, and stone ship-settings from

the Viking period. Just south of the modern village, we reached the most

prominent grave fields

with the close cropped turf emphasising the standing

stones. At the northern end, the stone outline of the Gettlinge ship-setting

survived with the entrance to the grave field marked by 2 prominent monoliths,

making a perfect picture even in today's poor light against the backdrop of a

19th century post-windmill on the brow of the ridge and a distant modern wind

farm (see above right) (Photo

29 - Gettlinge stone ship-setting). with the close cropped turf emphasising the standing

stones. At the northern end, the stone outline of the Gettlinge ship-setting

survived with the entrance to the grave field marked by 2 prominent monoliths,

making a perfect picture even in today's poor light against the backdrop of a

19th century post-windmill on the brow of the ridge and a distant modern wind

farm (see above right) (Photo

29 - Gettlinge stone ship-setting).

Ventlinge Camping:

our earlier investigation had left us in doubt as to where we should camp

tonight, and we returned south to Ventlinge, expecting to find just a couple of

places in the small campsite opposite the village church. To our surprise, the

driveway opened out into a large paddock behind the owner's house. We selected a

pitch over by the sturdy Öland dry-stone wall, looking out westwards across

arable land towards the Kalmar Sound, and walked over to book in (see left). Facilities,

although limited, were brand new and spotlessly clean, with site-wide wi-fi, at an all-inclusive price of 150kr/night. The owner greeted us with