A

Hanseatic Tour of the Baltic 2018 -

North-east and North-west Lithuania: A

Hanseatic Tour of the Baltic 2018 -

North-east and North-west Lithuania:

Kernavė Archaeological Site:

leaving Harmonie Camping on the dusty gravel road through the pine forests (see

below left), we returned to Rūdiškės, and from Trakai headed NW across country

to the Archaeological Reserve at Kernavė, one of Lithuania's most important

historical

sites (click on Map 1 right for our route). Set in the valley of the meandering Neris River, with ample fresh water

from tributary streams, plentiful food supplies, fertile soil for agriculture

and grazing, and 5 flat-topped hillocks above the valley bottom for protection

in times of threat, the site at Kernavė had been occupied continuously

since the late Palaeolithic 9th millennium BC. The Neris valley had been created

among moraine hills by Ice Age glacial melt-water, with side streams forming

gullies in the alluvium with intervening promontories forming hillocks which

later settlers levelled and fortified with wooden stockade hill-forts for

protection in troubled times. Soon after the retreat of the glaciers, migrant

hunter-gatherers initially set up temporary encampments in the Neris valley

hunting grounds, as evidenced by arrow-heads and other flint artefacts unearthed

at Kernavė from this period. historical

sites (click on Map 1 right for our route). Set in the valley of the meandering Neris River, with ample fresh water

from tributary streams, plentiful food supplies, fertile soil for agriculture

and grazing, and 5 flat-topped hillocks above the valley bottom for protection

in times of threat, the site at Kernavė had been occupied continuously

since the late Palaeolithic 9th millennium BC. The Neris valley had been created

among moraine hills by Ice Age glacial melt-water, with side streams forming

gullies in the alluvium with intervening promontories forming hillocks which

later settlers levelled and fortified with wooden stockade hill-forts for

protection in troubled times. Soon after the retreat of the glaciers, migrant

hunter-gatherers initially set up temporary encampments in the Neris valley

hunting grounds, as evidenced by arrow-heads and other flint artefacts unearthed

at Kernavė from this period.

|

Click on 2 highlighted areas

for details of

NE and NW Lithuania |

|

As the climate warmed and the valley became

forested, and with the domestication of plants and animals, the Kernavė

site was settled by Neolithic pastoralists during the 5th~3rd millennia BC. New

waves of migrants of Indo-European origins later settled the area, and during

the early metal age from the 2nd~1st millennia BC, bronze and iron implements

were forged by settlers at Kernavė. Into the early centuries of the Common

Era, the development of metallurgy and widespread use of iron working led to

increased productivity of foodstuffs, improvement in living conditions and

growth in population in the Neris valley by peoples considered ancestors of the

Baltic tribes. The first fortifications were built on the hillocks above the

Pajauta valley at Kernavė by the 3rd~4th centuries AD. Archaeological finds,

including a silver denarius of Marcus Aurelius dated to 161~2 AD showed that trade

developed with the Roman Province of Germania. Further migrations into the

region in the 5~6th centuries AD led to the divergence of the Balts into

distinctive tribes, with the direct ancestors of the Lithuanian people occupying

the tribal centre at Kernavė. The fortification of the Kernavė

hill-forts and prosperity of the township during the 11~13t As the climate warmed and the valley became

forested, and with the domestication of plants and animals, the Kernavė

site was settled by Neolithic pastoralists during the 5th~3rd millennia BC. New

waves of migrants of Indo-European origins later settled the area, and during

the early metal age from the 2nd~1st millennia BC, bronze and iron implements

were forged by settlers at Kernavė. Into the early centuries of the Common

Era, the development of metallurgy and widespread use of iron working led to

increased productivity of foodstuffs, improvement in living conditions and

growth in population in the Neris valley by peoples considered ancestors of the

Baltic tribes. The first fortifications were built on the hillocks above the

Pajauta valley at Kernavė by the 3rd~4th centuries AD. Archaeological finds,

including a silver denarius of Marcus Aurelius dated to 161~2 AD showed that trade

developed with the Roman Province of Germania. Further migrations into the

region in the 5~6th centuries AD led to the divergence of the Balts into

distinctive tribes, with the direct ancestors of the Lithuanian people occupying

the tribal centre at Kernavė. The fortification of the Kernavė

hill-forts and prosperity of the township during the 11~13t h centuries led to the

consolidation of the Lithuanian Balts into a distinct nation-state during the

reign of Grand Duke Mindaugas (1236~63). Under Grand Duke Traidenis (1269~82), Kernavė

became one of the most important economic and political centres of the Grand

Duchy of Lithuania, with the Duke's residence h centuries led to the

consolidation of the Lithuanian Balts into a distinct nation-state during the

reign of Grand Duke Mindaugas (1236~63). Under Grand Duke Traidenis (1269~82), Kernavė

became one of the most important economic and political centres of the Grand

Duchy of Lithuania, with the Duke's residence

occupying the central hill-fort of Akuras Hill, protected by a defensive system of forts on the surrounding hills.

A township of merchants and craftsmen developed in the Pajauta Valley on the

river's upper terrace at the foot of the hills. This was the period of the

Lithuanian Baltic tribes' conversion from paganism to Christianity. At the

beginning of the 14th century, Grand Duke Gediminas transferred the tribal

centre from Kernavė to Trakai and later to Vilnius. Kernavė continued

for some time as an important economic centre until attacks by the Teutonic

Knights (so-called Crusaders) finally resulted in Kernavė's destruction in

1390. The occupants deserted the settlement in the Pajauta Valley, and the site

was never again occupied. Alluvial deposits from the Neris covered the site and

medieval township, preserving it to be rediscovered by archaeologists in the

20th century. occupying the central hill-fort of Akuras Hill, protected by a defensive system of forts on the surrounding hills.

A township of merchants and craftsmen developed in the Pajauta Valley on the

river's upper terrace at the foot of the hills. This was the period of the

Lithuanian Baltic tribes' conversion from paganism to Christianity. At the

beginning of the 14th century, Grand Duke Gediminas transferred the tribal

centre from Kernavė to Trakai and later to Vilnius. Kernavė continued

for some time as an important economic centre until attacks by the Teutonic

Knights (so-called Crusaders) finally resulted in Kernavė's destruction in

1390. The occupants deserted the settlement in the Pajauta Valley, and the site

was never again occupied. Alluvial deposits from the Neris covered the site and

medieval township, preserving it to be rediscovered by archaeologists in the

20th century.

Shrouded in myths and legends, Kernavė

remains for Lithuanians a symbol of their statehood, the capital of pagan

ancestral tribes where Gediminas welded the Lithuanian Balts into a distinct nation-state and

converted them to Christianity. The name of Kernavė is first mentioned in

the Rhymed Chronicle and Hermanni de Watberge Chronicon Livoniae,

describing the Teutonic Order's 1279 raid into the Lithuanian realm as far as Kernavė.

Archaeological excavations by Vilnius University began in 1979, producing a

treasure trove of artefacts and grave goods spanning the 11 millennia of the Kernavė

site's occupation until the medieval township's destruction in 1390. These are

now displayed in the Kernavė Archaeological Museum, leading to Kernavė

being dubbed the Troy of Lithuania. Chronicle and Hermanni de Watberge Chronicon Livoniae,

describing the Teutonic Order's 1279 raid into the Lithuanian realm as far as Kernavė.

Archaeological excavations by Vilnius University began in 1979, producing a

treasure trove of artefacts and grave goods spanning the 11 millennia of the Kernavė

site's occupation until the medieval township's destruction in 1390. These are

now displayed in the Kernavė Archaeological Museum, leading to Kernavė

being dubbed the Troy of Lithuania.

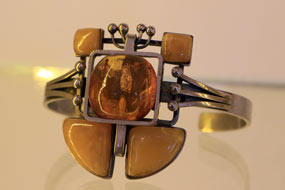

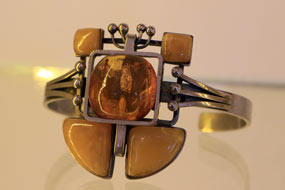

Our visit to Kernavė:

we initially visited the Kernavė Archaeological Museum to gain a fuller

understanding of the site's significance in Lithuanian history, and to view the

impressive and well-documented displays of excavated remains covering the entire

period of Kernavė's occupation, from Palaeolithic flint implements through

to the grave-goods of the medieval period at the time of the Lithuanian Balts'

conversion to Christianity and Kernavė's destruction. The displays included

beautiful medieval head band jewellery (see above left), brooches bearing the

Indo-European swastika emblem (see above right), Roman coins with head of Marcus Aurelius

(see above left), and a

medieval bronze statuette described as Perkūnas the pagan god of thunder

(Photo 1 - Perkūnas statuette).

Beyond the 19th century chapel, a path led over to a view point overlooking the

5 hill-forts, the Pajauta settlement site, and the Neris River meandering around

the valley beyond. Wooden step-ways led up onto

each of the steep-sided hill-fort sites,

and we climbed Castle Hill with its extensive flat-top site of the Grand Duke's

former residence, and the more narrow Mindaugas Hill. From both these

flat-topped hillocks views opened out of the other hill-forts, the narrow

winding Pajauta valley between them and the wide river terrace beyond, site of

the medieval township (Photo 2 - Kernavė hill-forts)

(see above right).

It was obvious from here why the Kernavė site should have been such an

attractively fertile spot for the original settlement (see right), and an valley beyond. Wooden step-ways led up onto

each of the steep-sided hill-fort sites,

and we climbed Castle Hill with its extensive flat-top site of the Grand Duke's

former residence, and the more narrow Mindaugas Hill. From both these

flat-topped hillocks views opened out of the other hill-forts, the narrow

winding Pajauta valley between them and the wide river terrace beyond, site of

the medieval township (Photo 2 - Kernavė hill-forts)

(see above right).

It was obvious from here why the Kernavė site should have been such an

attractively fertile spot for the original settlement (see right), and an

evidently

well-defended location for later Iron Age and medieval fortification (see above

left). Given the

site's historical importance, its magnificent state of preservation, and

invaluable range of archaeological finds representing 11th millennia of

occupation, it was understandable why Kernavė has such significance for

Lithuanians. evidently

well-defended location for later Iron Age and medieval fortification (see above

left). Given the

site's historical importance, its magnificent state of preservation, and

invaluable range of archaeological finds representing 11th millennia of

occupation, it was understandable why Kernavė has such significance for

Lithuanians.

North to Anykščiai and Camping Po Žvaigždėm: we now had a long drive north across

country to camp at Anykščiai in readiness for our planned ride on the

preserved narrow gauge railway tomorrow. Before leaving Kernavė however, we

phoned the Tourist Information Centre in Anykščiai to confirm that the

town's campsite was open. As in 2011, the lady's response in good English was

supremely helpful: yes the campsite was open and she would book space for us

with the warden; she also gave us contact details for tomorrow's railway ride.

From Kernavė, the A2 motorway took us 50kms NW in busy traffic to Utmergė (click

here for detailed map of route), then another 36 kms on A6/Route 120 to

the outskirts of the surprisingly large town of Anykščiai. We threaded a

way through the centre, across the river and in the far outskirts found

Camping Po Žvaigždėm (Under the Stars). We had expected this

to be deserted at this early stage of the year, but the riverside campsite was full of families noisily

celebrating Lithuanian Children's Day with party fun and games; it was bedlam!

The young warden was expecting us, having been alerted by the TIC Utmergė (click

here for detailed map of route), then another 36 kms on A6/Route 120 to

the outskirts of the surprisingly large town of Anykščiai. We threaded a

way through the centre, across the river and in the far outskirts found

Camping Po Žvaigždėm (Under the Stars). We had expected this

to be deserted at this early stage of the year, but the riverside campsite was full of families noisily

celebrating Lithuanian Children's Day with party fun and games; it was bedlam!

The young warden was expecting us, having been alerted by the TIC

lady of our

arrival, and welcomed us in quaintly formal English. The price was €22/night,

rather expensive for a basic municipal site, but the facilities including a good

kitchen were kept regularly cleaned; with trepidation at all the commotion, we

wearily settled in (see above left). The children's party finished at 9-00pm and peace was

restored. Earlier a text message was received confirming our seats on the Anykščiai

narrow gauge railway, but it was still uncertain as to whether the train would

run. lady of our

arrival, and welcomed us in quaintly formal English. The price was €22/night,

rather expensive for a basic municipal site, but the facilities including a good

kitchen were kept regularly cleaned; with trepidation at all the commotion, we

wearily settled in (see above left). The children's party finished at 9-00pm and peace was

restored. Earlier a text message was received confirming our seats on the Anykščiai

narrow gauge railway, but it was still uncertain as to whether the train would

run.

A ride on the preserved Anykščiai narrow gauge railway:

we needed to be up early the following

morning to be at Anykščiai station by 10-30 to collect tickets for our ride

on the narrow gauge railway. We were relieved to see crowds waiting and the train

being shunted into the platform. The Anykščiai 750mm gauge railway is a surviving part of

the former Tsarist-Russian network of local lines which once connected the rural hinterland to

major towns served by the Russian broad gauge main lines. This line linking Anykščiai

to Panevėžys was built in 1891; it ceased regular traffic in 2001 but was

re-opened by volunteers as a tourist attraction (see left). At the booking office, our

tickets were waiting, and after photographs of the train we took our reserved

seats

(Photo 3 - Anykščiai narrow gauge railway)

(see right).

The very growly ex-Soviet TU-2 diesel locomotive connected to the coaches (see

above right), and

at 11-00, with the sounding of klaxon horn and ringing of bell, the train

juddered and lurched out of the station for the 20km ride through the forests to

the isolated farming village of Troškūnai (see below left). From the little

rural station-halt, a guided walk in exhaustingly hot sun along field roads took

us to see the monastery church in Troškūnai, but with the commentary only

in Lithuanian we understood little of the church's history. traffic in 2001 but was

re-opened by volunteers as a tourist attraction (see left). At the booking office, our

tickets were waiting, and after photographs of the train we took our reserved

seats

(Photo 3 - Anykščiai narrow gauge railway)

(see right).

The very growly ex-Soviet TU-2 diesel locomotive connected to the coaches (see

above right), and

at 11-00, with the sounding of klaxon horn and ringing of bell, the train

juddered and lurched out of the station for the 20km ride through the forests to

the isolated farming village of Troškūnai (see below left). From the little

rural station-halt, a guided walk in exhaustingly hot sun along field roads took

us to see the monastery church in Troškūnai, but with the commentary only

in Lithuanian we understood little of the church's history.

Anykščiai

Holocaust Memorial: back

at Anykščiai we shopped for provisions at the Iki supermarket, and called in

at the TIC to thank the lady for her help; as so often is the case, less well

known and unpretentious places offer the very best of tourist information

services, and Anykščiai's TIC had set a standard which others could do well

to follow. We knew from our 2011 visit that pre-WW2 30% of Anykščiai's and

its neighbouring villages' population had been Jewish, all of whom had

been systematically exterminated by the German occupiers. We wanted to find the

monument marking the mass graves of the 2,500 Jewish people from this small

rural town who had been murdered by the Germans in the surrounding forests.

Just outside the town, a Anykščiai

Holocaust Memorial: back

at Anykščiai we shopped for provisions at the Iki supermarket, and called in

at the TIC to thank the lady for her help; as so often is the case, less well

known and unpretentious places offer the very best of tourist information

services, and Anykščiai's TIC had set a standard which others could do well

to follow. We knew from our 2011 visit that pre-WW2 30% of Anykščiai's and

its neighbouring villages' population had been Jewish, all of whom had

been systematically exterminated by the German occupiers. We wanted to find the

monument marking the mass graves of the 2,500 Jewish people from this small

rural town who had been murdered by the Germans in the surrounding forests.

Just outside the town, a sandy track led into the pine woods, and here we found

the small and sadly neglected Holocaust memorial with an almost faded

inscription and surrounded by a rusty fence (Photo 4 - Anykščiai Holocaust Memorial)

(see right). These now forgotten victims of German institutionalised mass-murder

now lay buried in mass graves in the sandy soil of the forests outside the town. sandy track led into the pine woods, and here we found

the small and sadly neglected Holocaust memorial with an almost faded

inscription and surrounded by a rusty fence (Photo 4 - Anykščiai Holocaust Memorial)

(see right). These now forgotten victims of German institutionalised mass-murder

now lay buried in mass graves in the sandy soil of the forests outside the town.

Arvydas Gaidelis Homestead-Camping at Palūšė:

our original plan had been to camp tonight at Papartis near to Molėtai, but what

in 2011 had been a straightforward site had now been tarted up as a lakeside

'resort' with silly prices to match, the sort of place where Lithuanian

townsfolk flock to party at weekends. We therefore decided to head directly to

Palūšė, and with the campsite there now closed, we had identified a small

guesthouse-camping in the village of Palūšė. In welcoming response to our

telephone enquiry, the owner's son in good

English recalled our earlier exchange

of emails confirming we could camp, and agreed to meet us at the homestead at

6-00pm this evening. We set course on the winding semi-tarmaced Route 119 for

the 44km drive, through Molėtai, an inconsequential little town with oversized

basilica, and joined Route 114 for the delightful 36km drive through pine

forested lakeland to Palūšė (click

here for detailed map of route). We arrived with time to spare, and in

the upper part of the village beyond the wooden church, the former Palūšė

Camping which we had so enjoyed in 2011 was now truly closed. We eventually

found the driveway leading to the homestead-camping, just as the owner Arvydas Gaidelis

arrived with his fluently English-speaking son. With insistent and kindly

hospitality, they English recalled our earlier exchange

of emails confirming we could camp, and agreed to meet us at the homestead at

6-00pm this evening. We set course on the winding semi-tarmaced Route 119 for

the 44km drive, through Molėtai, an inconsequential little town with oversized

basilica, and joined Route 114 for the delightful 36km drive through pine

forested lakeland to Palūšė (click

here for detailed map of route). We arrived with time to spare, and in

the upper part of the village beyond the wooden church, the former Palūšė

Camping which we had so enjoyed in 2011 was now truly closed. We eventually

found the driveway leading to the homestead-camping, just as the owner Arvydas Gaidelis

arrived with his fluently English-speaking son. With insistent and kindly

hospitality, they explained that what had been grandmother's house was now being

converted to holiday accommodation, and we were welcome to camp in the

grounds. They opened up, found us power, and left the key so that we could use

the bathroom and kitchen, all for €13/night. We settled in at a flat area

alongside the house in the shade of pine trees, a perfectly peaceful forest

setting for our day in camp tomorrow and visit to Aukštaitija National Park (see left) (Photo 5 - Arvydas Gaidelis Guesthouse-Camping).

We spent a productive rest day at the guesthouse-camping, and Arvydas the owner

broke off from his conversion work to invite us to share morning coffee with him

sat on the veranda. He spoke no English but we manage to converse with him in

German, a truly hospitable man. The facilities in the guest-house were excellent

with full access to both bathroom, kitchen and wi-fi. It was truly a memorable

stay explained that what had been grandmother's house was now being

converted to holiday accommodation, and we were welcome to camp in the

grounds. They opened up, found us power, and left the key so that we could use

the bathroom and kitchen, all for €13/night. We settled in at a flat area

alongside the house in the shade of pine trees, a perfectly peaceful forest

setting for our day in camp tomorrow and visit to Aukštaitija National Park (see left) (Photo 5 - Arvydas Gaidelis Guesthouse-Camping).

We spent a productive rest day at the guesthouse-camping, and Arvydas the owner

broke off from his conversion work to invite us to share morning coffee with him

sat on the veranda. He spoke no English but we manage to converse with him in

German, a truly hospitable man. The facilities in the guest-house were excellent

with full access to both bathroom, kitchen and wi-fi. It was truly a memorable

stay . .

Aukštaitija National Park: first stop this morning was the Aukštaitija

National Park Information Office in Palūšė village for an

English version of the free-issue national park guide book. We also asked more

about the traditional carved wooden Contemplative Christ shrine-statues, called

Rūpintojėlis in Lithuanian, seen in rural parts of the country. Up on the

hillside above the village by the mid-18th century wooden Church of St Jozef (see above right

and left) overlooking Lake Lušiai, such a Rūpintojėlis stood in

the churchyard (Photo

6 - Palūšė Rūpintojėlis). Armed with a

detailed map and good advice from the National Park

office in the village, we

set off from Palūšė for a day's walking among the hillocks and  lakes

of the Aukštaitija National Park, turning off onto a

back lane to Antalksnė village where a stork was foraging for prey by the

road-side (Photo

7 - Foraging stork). The Šiliniškės esker-ridge, one of Aukštaitija

National Park's prominent geographical features, starts at the look-out point of

Ladakalnis Hill. This 175m hillock is believed to have been the site of

pre-Christian sacrifices to the pagan goddess Lada, the Great Mother who

according to legend gave birth to the world. It took us all of 10 minutes to

climb steeply to its 'summit', but the view of 6 surrounding lakes made it

worthwhile (see right). The path along the spine of the Šiliniškės esker was delightful with glimpses of surrounding lakes through the pine and oak woods

covering the narrow moraine-ridge (Photo

8 - Šiliniškės esker-ridge). The ridge path led lakes

of the Aukštaitija National Park, turning off onto a

back lane to Antalksnė village where a stork was foraging for prey by the

road-side (Photo

7 - Foraging stork). The Šiliniškės esker-ridge, one of Aukštaitija

National Park's prominent geographical features, starts at the look-out point of

Ladakalnis Hill. This 175m hillock is believed to have been the site of

pre-Christian sacrifices to the pagan goddess Lada, the Great Mother who

according to legend gave birth to the world. It took us all of 10 minutes to

climb steeply to its 'summit', but the view of 6 surrounding lakes made it

worthwhile (see right). The path along the spine of the Šiliniškės esker was delightful with glimpses of surrounding lakes through the pine and oak woods

covering the narrow moraine-ridge (Photo

8 - Šiliniškės esker-ridge). The ridge path led

to Ginučiai

castle-mound, an elongated conical hill which had been the site of a 10th

century network of defensive hill-forts built by Lithuanian tribes to withstand

incursions by Teutonic Knights (see left) (Photo

9 - Ginučiai hill-fort). The flat hill-top was crowned by a

memorial stone commemorating a visit in 1934 by the autocratic president of

Lithuania, Antanas Smetona,who had planted an oak at this historic site;

the Soviets destroyed the oak during their long occupation, causing Lithuanians

to treat the place with even greater reverence; Smetona may have been a

dictator, but at least he was a Lithuanian dictator! With the sun filtering down

through the pines, this was a magnificent path with views out across the

Aukštaitija lakes (see below right). to Ginučiai

castle-mound, an elongated conical hill which had been the site of a 10th

century network of defensive hill-forts built by Lithuanian tribes to withstand

incursions by Teutonic Knights (see left) (Photo

9 - Ginučiai hill-fort). The flat hill-top was crowned by a

memorial stone commemorating a visit in 1934 by the autocratic president of

Lithuania, Antanas Smetona,who had planted an oak at this historic site;

the Soviets destroyed the oak during their long occupation, causing Lithuanians

to treat the place with even greater reverence; Smetona may have been a

dictator, but at least he was a Lithuanian dictator! With the sun filtering down

through the pines, this was a magnificent path with views out across the

Aukštaitija lakes (see below right).

Villages of Aukštaitija National Park:

back along the ridge, we continued with our circular route through the villages

of Aukštaitija National Park. At a junction of lanes just before Kirdeikiai,

we found a classic example of the traditional carved wooden folk-art wayside

shrine incorporating the figure of the Contemplative Christ, the Rūpintojėlis,

seen throughout the country; our photograph may well form the subject of our

2018 Christmas card (see below left) (Photo

10 - Aukštaitija Rūpintojėlis). Reaching Ginučiai

village we found the conserved water-mill, the only one of 6 original

water-mills in Aukštaitija National Park whose early 19th century mechanism is

still in working order (see below right). The

English-speaking young guide showed us around the

mill, and although most of the mechanism was wooden, the design of the

water-mill's metal turbine blades reminded us of modern HEP turbines seen at Porjus generating station in Northern Sweden. Continuing our drive along further

eskers separating small lakes, we reached Trainiškis village where another

ancient carved wooden Rūpintojėlis stood among the cottages.

The final village of Vaišniūnai was a more work-a-day place with farmsteads and

a hill-top graveyard, and from here Route 102 brought us into the small town of

Ignalina for provisions at the Maxima supermarket. English-speaking young guide showed us around the

mill, and although most of the mechanism was wooden, the design of the

water-mill's metal turbine blades reminded us of modern HEP turbines seen at Porjus generating station in Northern Sweden. Continuing our drive along further

eskers separating small lakes, we reached Trainiškis village where another

ancient carved wooden Rūpintojėlis stood among the cottages.

The final village of Vaišniūnai was a more work-a-day place with farmsteads and

a hill-top graveyard, and from here Route 102 brought us into the small town of

Ignalina for provisions at the Maxima supermarket.

Aukštaitija

National Park Botanical Trail: after a final night at Arvydas Gaidelis

Homestead-Camping, a shift of wind around to the north brought markedly lower

temperatures: 10şC felt positively Arctic after recent days' heat-wave! Before

leaving Palūšė, there was time to walk the 3.5km Aukštaitija Botanical

Trail. The path climbed steeply up from the shore of Lake Lušiai onto a broad

plateau covered with delightful pine, spruce, rowan and oak woods. The forest

floor was a mass of fresh green Bilberry just showing signs of its new

berries and leathery-leaved Lingonberry. Both in the higher forest and lower

moist area by a water-course, the feast of botanical gems truly justified the

path's description, with Lily of the Valley, Stone Bramble, Solomon's Seal, Wood

Sorrel, Cow Wheat, May Lily, Chickweed Wintergreen, Water Avens, Herb Paris, Marsh Spotted Orchids, Marsh Tormentil and Bog Beans. But the prize came when we

crossed the marshland on a board-walk: here among the sphagnum, large clumps of

Cranberry flowers flourished (Photo

11 - Cranberry flowers). The path continued through further woodland meadows to round the head of a lake, climb back onto higher areas of pine

forest, and return along the shore of Lake Lušiai (see below left). It had truly

been a rewarding walk. Aukštaitija

National Park Botanical Trail: after a final night at Arvydas Gaidelis

Homestead-Camping, a shift of wind around to the north brought markedly lower

temperatures: 10şC felt positively Arctic after recent days' heat-wave! Before

leaving Palūšė, there was time to walk the 3.5km Aukštaitija Botanical

Trail. The path climbed steeply up from the shore of Lake Lušiai onto a broad

plateau covered with delightful pine, spruce, rowan and oak woods. The forest

floor was a mass of fresh green Bilberry just showing signs of its new

berries and leathery-leaved Lingonberry. Both in the higher forest and lower

moist area by a water-course, the feast of botanical gems truly justified the

path's description, with Lily of the Valley, Stone Bramble, Solomon's Seal, Wood

Sorrel, Cow Wheat, May Lily, Chickweed Wintergreen, Water Avens, Herb Paris, Marsh Spotted Orchids, Marsh Tormentil and Bog Beans. But the prize came when we

crossed the marshland on a board-walk: here among the sphagnum, large clumps of

Cranberry flowers flourished (Photo

11 - Cranberry flowers). The path continued through further woodland meadows to round the head of a lake, climb back onto higher areas of pine

forest, and return along the shore of Lake Lušiai (see below left). It had truly

been a rewarding walk.

A re-visit to Ignalina Nuclear Power Station,

and many unanswered questions:

beyond Ignalina, we set off on the second part of our day to re-visit the

Ignalina Nuclear Power Station and the town of Visaginas built by the Soviets to

house the power plant's workers (click

here for detailed map of route). Route 102 passed through rolling

agricultural countryside, causing us to observe that during our travels around

Lithuania, we had so far seen little evidence of large scale cereal crops; no fields of wheat, barley and certainly  no maize. The countryside seemed to be

confined to meadow-grassland, but with little or none cut for

hay. Other than forests, we had also seen large tracts of seemingly unusable,

infertile land particularly in the south of the country, and along with this

apparent absence of arable farming, we had seen little evidence of cattle or

sheep grazing, just the occasional tethered cow on small-holdings. So with all

this grassland seemingly little used, where was Lithuania's agricultural

production, we wondered? no maize. The countryside seemed to be

confined to meadow-grassland, but with little or none cut for

hay. Other than forests, we had also seen large tracts of seemingly unusable,

infertile land particularly in the south of the country, and along with this

apparent absence of arable farming, we had seen little evidence of cattle or

sheep grazing, just the occasional tethered cow on small-holdings. So with all

this grassland seemingly little used, where was Lithuania's agricultural

production, we wondered?

The Soviets had chosen this remote and

uninhabited NE corner of Lithuania, tucked away among the swamps and forests on

the shores of Lake Drūkšiai in the angle between Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus,

to build Ignalina Nuclear Power Station in 1974. Visaginas had also been built

nearby as a new town of apartment blocks, hacked out of this remote and

inhospitable wilderness, to house the 5,000

Russian workers and their families

brought in as immigrants from other parts of the USSR. Ignalina, the only

nuclear power station in the Baltic States, had 2 water-cooled, graphite

moderated nuclear reactors of the same design as the Chernobyl plant in Ukraine

which suffered the disastrous melt-down in 1986. Ignalina's Reactor #1 came

on-line in 1984, but Reactor #2 was delayed until 1987 because of Chernobyl. Ignalina's 2 reactors, originally the world's most powerful, had the capacity to

generate an electrical output of 1,500 megawatts. But the plant's design

similarities with Chernobyl and the lack of containment building in the event of

nuclear accident was cited by the EU as ultra high risk, and the power plant's

phased decommissioning was insisted on as a pre-condition to Lithuania's accession

to EU membership in 2004. The Lithuanian government was compelled to accept this

in spite of the economic consequences of finding alternative energy supplies,

given that Ignalina had produced 70% of the country's electrical supply needs.

The EU agreed to Russian workers and their families

brought in as immigrants from other parts of the USSR. Ignalina, the only

nuclear power station in the Baltic States, had 2 water-cooled, graphite

moderated nuclear reactors of the same design as the Chernobyl plant in Ukraine

which suffered the disastrous melt-down in 1986. Ignalina's Reactor #1 came

on-line in 1984, but Reactor #2 was delayed until 1987 because of Chernobyl. Ignalina's 2 reactors, originally the world's most powerful, had the capacity to

generate an electrical output of 1,500 megawatts. But the plant's design

similarities with Chernobyl and the lack of containment building in the event of

nuclear accident was cited by the EU as ultra high risk, and the power plant's

phased decommissioning was insisted on as a pre-condition to Lithuania's accession

to EU membership in 2004. The Lithuanian government was compelled to accept this

in spite of the economic consequences of finding alternative energy supplies,

given that Ignalina had produced 70% of the country's electrical supply needs.

The EU agreed to pay €820 million towards decommissioning costs with

compensation payments continuing until 2013. Reactor #1 closed in 2004, followed

by the decommissioning of Reactor #2 in 2009, and construction of improved

containment storage for radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel rods. The

plant's closure resulted in severe economic, social and political consequences

for Lithuania. It had provided the major source of employment for the people of Visaginas, and EU compensation made little impact on bringing alternative

employment in so remote and isolated a region. Attempts to negotiate financing

with international investment companies of a replacement nuclear plant at

Ignalina have met delays, and any start date remains

pay €820 million towards decommissioning costs with

compensation payments continuing until 2013. Reactor #1 closed in 2004, followed

by the decommissioning of Reactor #2 in 2009, and construction of improved

containment storage for radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel rods. The

plant's closure resulted in severe economic, social and political consequences

for Lithuania. It had provided the major source of employment for the people of Visaginas, and EU compensation made little impact on bringing alternative

employment in so remote and isolated a region. Attempts to negotiate financing

with international investment companies of a replacement nuclear plant at

Ignalina have met delays, and any start date remains

uncertain. Meanwhile

Lithuania has had to bear the cost of extending the capacity of its fossil fuel

generating stations and buying electricity and gas from Russia, placing it at

the mercy of its all-powerful eastern neighbour, a clear cause of concern

particularly since Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea. Against this background,

we had been able to make a free of charge visit to Ignalina in 2011 to learn

more about the workings of the reactors and the social, political and economic

impact both at local and national level of the EU-enforced closure programme.

Official visits now to Ignalina are charged at more than €50 which was clearly

out of the question. We did however want to find out more while in this part of

Lithuania about what progress had been made in the intervening 7 years with

replacing the power plant's outmoded reactors. We should have to rely on our own

observations. uncertain. Meanwhile

Lithuania has had to bear the cost of extending the capacity of its fossil fuel

generating stations and buying electricity and gas from Russia, placing it at

the mercy of its all-powerful eastern neighbour, a clear cause of concern

particularly since Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea. Against this background,

we had been able to make a free of charge visit to Ignalina in 2011 to learn

more about the workings of the reactors and the social, political and economic

impact both at local and national level of the EU-enforced closure programme.

Official visits now to Ignalina are charged at more than €50 which was clearly

out of the question. We did however want to find out more while in this part of

Lithuania about what progress had been made in the intervening 7 years with

replacing the power plant's outmoded reactors. We should have to rely on our own

observations.

Beyond Dūkštas, we turned off towards Visaginas

following the branch-line railway that led to Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant. The

approach passed the insulated pipelines which, while Ignalina was operating,

supplied waste steam from the power station to heat Visaginas' apartment blocks.

The pipeline appeared still in well-maintained condition but presumably was no

longer in use since the plant's closure. We turned towards the power station

following the pipeline, and what was immediately evident were the continuous

streams of cars travelling from the plant towards Visaginas. With the 2 former

reactors now decommissioned and the plant no longer generating, we had assumed that

the number of workers would now be much reduced. Clearly however this was not

the case: a shift was now ending with many employees commuting to/from Visaginas.

As we turned into the main Ignalina driveway, huge numbers of cars were emerging

from staff car parks and lines of buses waited to transport workers home. We

paused to allow traffic to clear as staff went off shift, and took our photos of

the prominent triple chimneys of the former #1 reactor (Photo

12 - Ignalina Nuclear Power Station). (see above left and right) What on earth did all

these workers do, we puzzled, if the plant was effectively closed and no longer

generating, with no agreement yet reached on construction of a replacement

western-design replacement reactor? ending with many employees commuting to/from Visaginas.

As we turned into the main Ignalina driveway, huge numbers of cars were emerging

from staff car parks and lines of buses waited to transport workers home. We

paused to allow traffic to clear as staff went off shift, and took our photos of

the prominent triple chimneys of the former #1 reactor (Photo

12 - Ignalina Nuclear Power Station). (see above left and right) What on earth did all

these workers do, we puzzled, if the plant was effectively closed and no longer

generating, with no agreement yet reached on construction of a replacement

western-design replacement reactor?

In search of further answers, we drove along

the rear roadway around to the buildings that had formerly housed the #2 reactor

with the triple exhaust chimney

emerging from its roof

(see above right)

(Photo

13 - Reactor #2 building). There were a number of

newer industrial premises occupying smaller buildings, but we could get no

closer in our search for further information. Back around the front of the main

building, more employees were coming off shift. One of these, who seemed

to be

more senior in status, approached us with warnings about our obvious

vulnerability with the plant's security in our taking photographs. We seized the

opportunity to ask questions about Ignalina's status. His replies, full of pride

about the station's capacity, seemed to indicate that the plant was still

generating and feeding the grid. But how was this possible if the reactors were

now de-commissioned, and in that case what did all these staff do? His answers

perhaps reflected a nostalgia for Ignalina's working days, but we were not going

to get more information as he rushed away, clearly embarrassed by our probing

questions. What was the current status of Ignalina? How far have discussions on investment in replacement

reactors reached? Is the plant is generating or not? Are the power lines

emerging from the plant carrying current to the grid or not? (see above left) Neither the Official

Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant web site nor any other web site gives answers to

these questions. Yet we had witnessed 100s of employees coming off shift at Ignalina; what do they all currently work at

with no evident progress on the much vaunted new reactor? Our many questions about Ignalina remained unanswered. But we at least had some photos, and we also beat a hasty retreat

before our presence triggered a security alert! to be

more senior in status, approached us with warnings about our obvious

vulnerability with the plant's security in our taking photographs. We seized the

opportunity to ask questions about Ignalina's status. His replies, full of pride

about the station's capacity, seemed to indicate that the plant was still

generating and feeding the grid. But how was this possible if the reactors were

now de-commissioned, and in that case what did all these staff do? His answers

perhaps reflected a nostalgia for Ignalina's working days, but we were not going

to get more information as he rushed away, clearly embarrassed by our probing

questions. What was the current status of Ignalina? How far have discussions on investment in replacement

reactors reached? Is the plant is generating or not? Are the power lines

emerging from the plant carrying current to the grid or not? (see above left) Neither the Official

Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant web site nor any other web site gives answers to

these questions. Yet we had witnessed 100s of employees coming off shift at Ignalina; what do they all currently work at

with no evident progress on the much vaunted new reactor? Our many questions about Ignalina remained unanswered. But we at least had some photos, and we also beat a hasty retreat

before our presence triggered a security alert!

Soviet-built town of

Visaginas:

the last time we visited Visaginas in 2011, many of the blocks of Soviet era

panelaky looked run-down, Russian was the predominant language heard spoken,

and Cyrillic signs could be seen everywhere. Today the town had a curiously more

thriving air, apartment blocks looked less drab, and Lithuanian was heard, no

different from any other Lithuanian town. We drove around the ring road, and cut

through to the Iki supermarket for our shopping, where the lady at the check-out

addressed us in Lithuanian. After photos of the town's Soviet era panelaky at

Partizanų gatvė

(Photo

14 - Soviet era panelaky at Visaginas) (see above left), we circled around

the highway passing the monument displaying today's date which once also

incorporated radiation levels from its Geiger counter (see above right), proudly

announcing that the nearby presence of Soviet-designed

nuclear reactors posed no

environmental threat (try telling that to the former citizens of Chernobyl!). We

eventually located the Russian Orthodox

church built to serve the town's once

Russian dominated population of Ignalina workers (see right). Like the

power plant, Visaginas in 2018 posed unanswered questions about how, in spite of the

unemployment assumed from Ignalina's reported closure, the town now seemed

enigmatically lively and prosperous. church built to serve the town's once

Russian dominated population of Ignalina workers (see right). Like the

power plant, Visaginas in 2018 posed unanswered questions about how, in spite of the

unemployment assumed from Ignalina's reported closure, the town now seemed

enigmatically lively and prosperous.

NW to Zarasai:

returning to Route 102, we headed NW towards Zarasai (click

here for detailed map of route) and joined Route 6 into the town which

stood so close to the Latvian border. We had stayed at Zarasai Camping in 2011

and pitched this evening in the tree-sheltered enclosure tucked away in the

corner overlooking the lake (see left). After the last few weeks' heat-wave

conditions, our instinct was for shade from the hot sun in readiness for

tomorrow's rest day, but in contrast today we needed shelter from the

northerly wind blowing from across the lake. We struggled to pitch against the wind, shivering

in the chill air. Such a change in temperature was a total surprise, and by the

time we were settled, we needed sweaters, roof vents closed against the cold

drafts, and even the fan-heater on; unimaginable after recent weather. What a

multi-aspect today had been; orchids to atoms, forests to panelaky, and

we cooked supper still perplexed by the unanswered questions raised by Ignalina

NPP and Visaginas.

blowing from across the lake. We struggled to pitch against the wind, shivering

in the chill air. Such a change in temperature was a total surprise, and by the

time we were settled, we needed sweaters, roof vents closed against the cold

drafts, and even the fan-heater on; unimaginable after recent weather. What a

multi-aspect today had been; orchids to atoms, forests to panelaky, and

we cooked supper still perplexed by the unanswered questions raised by Ignalina

NPP and Visaginas.

A day in camp at Zarasai Camping:

a chill night, and although the wind had dropped, the weather remained cool

and overcast for our day in camp. Zarasai Camping was a straightforward little

site, and with its friendly welcome, lovely lakeside setting, good facilities

and reasonable price of €17/night, it

still deserved its +5 rating. We settled up

with the wardens, a smilingly friendly elderly couple, she speaking German

and he speaking hesitant English. Their young grandson was visiting from

Belfast; imagine a little Lithuanian lad speaking English with a broad Ulster

accent! Late afternoon the cloud broke to give evening sun, and after supper we

walked down to the lake for sunset photos through the silhouetted trees from the

landing-stage looking across Lake Zarasai (see above right)

(Photo

15 - Sunset across Lake Zarasai). still deserved its +5 rating. We settled up

with the wardens, a smilingly friendly elderly couple, she speaking German

and he speaking hesitant English. Their young grandson was visiting from

Belfast; imagine a little Lithuanian lad speaking English with a broad Ulster

accent! Late afternoon the cloud broke to give evening sun, and after supper we

walked down to the lake for sunset photos through the silhouetted trees from the

landing-stage looking across Lake Zarasai (see above right)

(Photo

15 - Sunset across Lake Zarasai).

A visit to Zarasai:

we woke to a sunny morning, and before moving on today back into Central

Lithuania, we paid a brief re-visit to Zarasai. This modest and unassuming

little town grew from a 16th century rural settlement, and was formally laid out

with Tsarist era town planning around a grid of streets radiating from the

parkland central town square of Sėlių Aikštė. The town developed over a

peninsula of Lake Zarasai along the Kaunas~Daugavpils section of the

Warsaw~St Petersburg highway, the completion of which in 1830 is celebrated by a

prominent commemorative obelisk on Vytauto gatvė. We shopped for provisions at

the Maxima supermarket before parking at Sėlių Aikštė, calling in a the

council offices for a town plan, and walking across the attractively tree-shaded

parkland to photograph Zarasai's grandiose neo-Baroque St Mary's Ascension

church, built at the time of the 19th century expansion of the town (Photo

16 - St Mary's Ascension church at Zarasai) (see above left).

Utena and the Museum of the Struggles for Freedom:

leaving Zarasai, we headed SW back into Lithuania's

heartlands on the Route 6 highway, the modern successor to the 19th century

Tsarist road linking cities of the Empire (click

here for detailed map of route). Despite the numbers of heavy trucks

seen passing through Zarasai, Route 6 was remarkably traffic-free, cutting a

straight course across the undulating rural countryside. Again we remarked on

the seemingly under-usage made of Lithuania's vast agricultural land resources,

with endless tracts of uncut, un-grazed grassland. We covered the 50kms in less

than an hour to approach the outskirts of Utena, rated by us as Lithuanian

Non-Entity Town of the Year on our 2011 visit. Earlier today, we had tried

phoning the Utenos Brewery, part of the Carlsberg Empire, in a attempt to

arrange a visit. In line with our 2011 experience, there was no reply. We did

however receive a return call to say that, although brewery visits were limited

to groups of 10 or more, someone would try to arrange something for us; a

further call said that no one was available so no brewery visit would be

possible. It cannot be said that we were disappointed; so far we had

consistently avoided Utenos beers as being, like all the Carlsberg products,

little better than coloured water! With little or no expectations of Utena, we

drove along the main street of Basanavičiaus gatvė in search of the TIC,

passing the statue of the eponymous 19th century ideologist of the Lithuanian

national movement at the central cross-roads. The coordinates led to the far end

of town, an unlikely location for the tourist office so remote from the centre.

But this turned out to be Utena's former railway station, now converted to TIC

with decorative statuesque figures waiting on the platform for a train that

would now no longer arrive. The erstwhile station at Utena had been on the same

narrow gauge line as Anykščiai linking to the main Soviet broad gauge main line

at Panevėžys. Inside the 2 members of staff sat guard over piles of mostly

outdated brochures all relating to places other than Utena. It almost seemed a

tacit acknowledgement that no one would want to visit such a non-entity place as

Utena! With apparent surprise at having customers, the ladies served us with

unaccustomed enthusiasm, managing to find a glossy booklet filled with trivial

irrelevancies about the Utena region. Our chance observation that 2018 marked

the 27th anniversary of Lithuania regaining independence prompted her to mention

a small museum next door recalling the evil years of Soviet occupation. The

museum's attendant seemed equally surprised to receive interest, but in fact the Utena Museum of the Struggles for Freedom had well-presented displays,

documented with English translations, detailing the Stalin-led occupation of

Lithuania, deportations and loss of freedom, collectivization of agriculture,

forced conscription of Lithuanians into the Red Army, and partisan resistance

until as late as 1965. The museum's theme of post-WW2

repression in Lithuania,

with emphasis on the Utena region, was contrasted with the same period of

freedom and recovery in Western Europe with the foundation of NATO, UNICEF and

the Welfare State. This modest little museum with its charmingly unassuming

attendant must rank as Utena's one and only worthwhile highlight and we were glad

to have discovered it despite the lack of publicity. repression in Lithuania,

with emphasis on the Utena region, was contrasted with the same period of

freedom and recovery in Western Europe with the foundation of NATO, UNICEF and

the Welfare State. This modest little museum with its charmingly unassuming

attendant must rank as Utena's one and only worthwhile highlight and we were glad

to have discovered it despite the lack of publicity.

Sudeikiai Camping near Utena: with nothing else in Utena to detain us, we drove back through

the town and turned off for the 8kms out to Sudeikiai Camping. On our stay here

in 2011, this lakeside municipal campsite had been rated as overpriced compared

with the equivalent site at Zarasai. Apart from a lone Dutch camping-car, the

place was deserted, and we pitched down at the far end in an open area, less

concerned now with seeking shade from trees despite the sun being warm.

Facilities were identical to those at Zarasai with a well-equipped

kitchen/common room. Reception was deserted but the young warden called round

later for payment of the charge, now reduced to a more reasonable €16/night. The

following morning a bright, warm sun rose above the surrounding trees, and

fieldfares pecked around as we sat out for breakfast in the campsite's peaceful

parkland (see right). When it came to washing up however, we found the kitchen/common room locked. A phone call to the campsite number to request that

someone attend to open up, followed by a 20 minute wait and need for a second

phone call added to the frustration, delaying our being able to get away for

today's long drive to the Biržai region.

NW to the Biržai region: Route 118 took us

north-westwards towards Kupiskis (click

here for detailed map of route). After seeing little traces of active

agriculture in other parts of the country, we now travelled through a

well-farmed region with fields cut for baled hay, sizeable herds of grazing

dairy cattle, and large scale arable farming with fields of ripening wheat and

rye. The sun

this morning was dazzlingly bright, making this a long and wearying

drive, but beyond the large farming village of Vabalninkas, we eventually

approached Biržai. Lithuania's northernmost town of Biržai

developed as a

trading post from the 15th century under the ownership of the aristocratic

Radvila family. The town's fortified castle was built by Duke Kristupas Radvila

the Thunderer in 1586 to guard the northern frontier of the Lithuanian Grand

Duchy. It was twice destroyed by the invading Swedish Empire during the Northern

Wars and finally abandoned in the early 18th century, with only parts of a

ruined gateway surviving of the original castle. The fortress was restored and

reconstructed as a Renaissance palace in the 1980s, and now houses the town

library and museum. Biržai's other claim to fame is the stately Astravas Manor

built as a summer retreat by the Tyszkiewicz family in the 1860s after the

Radvilas had sold them the Biržai estates in 1812. The manor stands on the

northern shore of Lake Šivėna, created artificially in 1575 by damming the

confluence of the Apaščia and Agluona Rivers as part of the town's defences. The

lake is spanned by a 525m long wooden footbridge built in 1928 to link Astravas

Manor to the town. developed as a

trading post from the 15th century under the ownership of the aristocratic

Radvila family. The town's fortified castle was built by Duke Kristupas Radvila

the Thunderer in 1586 to guard the northern frontier of the Lithuanian Grand

Duchy. It was twice destroyed by the invading Swedish Empire during the Northern

Wars and finally abandoned in the early 18th century, with only parts of a

ruined gateway surviving of the original castle. The fortress was restored and

reconstructed as a Renaissance palace in the 1980s, and now houses the town

library and museum. Biržai's other claim to fame is the stately Astravas Manor

built as a summer retreat by the Tyszkiewicz family in the 1860s after the

Radvilas had sold them the Biržai estates in 1812. The manor stands on the

northern shore of Lake Šivėna, created artificially in 1575 by damming the

confluence of the Apaščia and Agluona Rivers as part of the town's defences. The

lake is spanned by a 525m long wooden footbridge built in 1928 to link Astravas

Manor to the town.

Our reason for visiting this far northern area

of Lithuania almost at the Latvian border was that Biržai is curiously a region

of Karstic limestone with over 9,000 sink holes where underground dissolution of the soft white gypsum by percolating groundwater has caused subsidence. The

surface layer of soil and vegetation collapses creating sink holes. This area of

Karst topography is an outcropping of Devonian limestone bedrock emerging from

the overlaying covering of glacial alluvium spread by the retreating glaciers of

the last Ice Age which makes up most of the Baltic landscape. limestone bedrock emerging from

the overlaying covering of glacial alluvium spread by the retreating glaciers of

the last Ice Age which makes up most of the Baltic landscape.

Hot and weary after a long drive, we made first for the Biržai Regional Park

Information Office for maps and details of the sink holes. We were greeted

by a youngster from Georgia working here on an EU exchange scheme before

completing his university education back at Tbilisi. In commendably fluent

English, he explained the geological nature of the Karstic terrain and the

subterranean dissolution resulting in sudden surface subsidence forming sink

holes, and showed us core samples of gypsum from regional bore holes. In

addition to this geological background understanding, we also gained maps and

the locations of the principal sink holes and other Karstic features. It was an

interesting encounter and we also learned more about Georgia, a

country about

which we had known little. We stocked up with provisions at the Biržai Iki

supermarket, having learned that Iki in Lithuanian means See you soon

(as opposed to the more formal Viso gero for Goodbye). At the TIC,

we got details of Biržai's micro-breweries, for which the town was renowned. The

largest of these was Rinkuškiai Brewery which we found on the far side of town.

It was clearly a sizeable and enterprising micro-brewery, profitably geared to

restaurant trade and beer-tasting, with large groups of visitors. We bought a

range of their beers, and arranged a visit to the brewery tomorrow after our

tour of the Karst sink holes. country about

which we had known little. We stocked up with provisions at the Biržai Iki

supermarket, having learned that Iki in Lithuanian means See you soon

(as opposed to the more formal Viso gero for Goodbye). At the TIC,

we got details of Biržai's micro-breweries, for which the town was renowned. The

largest of these was Rinkuškiai Brewery which we found on the far side of town.

It was clearly a sizeable and enterprising micro-brewery, profitably geared to

restaurant trade and beer-tasting, with large groups of visitors. We bought a

range of their beers, and arranged a visit to the brewery tomorrow after our

tour of the Karst sink holes.

Biržai Camping: Biržai's municipal

camp site, established only 4 years ago, is set in a delightfully grassy area by

Lake Šivėna and the town stadium, and shaded by mature oak trees. We were

greeted with ebullient enthusiasm by the young warden who insisted on giving us

further details of the town's attractions when, weary after a long day, all we

wanted to do was to get pitched under the shady oak trees and relax with bottles

of Rinkuškiai beers! Our peaceful evening was enlivened by a football match at

the neighbouring stadium, and later a magnificent sunset and after-glow over the

lake. a long day, all we

wanted to do was to get pitched under the shady oak trees and relax with bottles

of Rinkuškiai beers! Our peaceful evening was enlivened by a football match at

the neighbouring stadium, and later a magnificent sunset and after-glow over the

lake.

A day in

Biržai's Karst limestone country: reserving our pitch, we set off the following

morning for our day of exploration around Biržai's Karst limestone

country, and just 1km on the far side of the town we reached the parking area

for the most well known of the Karst features. The entire woodland area was

riddled with depressions and sink holes (Photo

17 - Karst sink holes) (see above left and right), where dissolution of the subterranean

soft gypsum had over the years caused subsidence. A path led over to the largest

of the sink holes, the so-called Cow Hole (Karvės Ola), where steep wooden steps

led down into the bottom of the 12m deep, 10m wide pit (Photo

18 - Cow Hole Karst sink hole) (see above left and right). The limestone strata,

exposed by the severe subsidence which had created the pit, were visible just

below the shallow surface soil and vegetation. Rather

hesitantly we scrambled

down into the base of the pit, and examined other nearby sink holes and

depressions dotted among the surrounding woodland. base of the pit, and examined other nearby sink holes and

depressions dotted among the surrounding woodland.

The lane led along to the Geologists' Sink Hole,

where in 2003 a wide depression had opened up in open agricultural countryside,

revealing the white limestone strata just below the surface soil (see left) (Photo

19 - Geologists' sink hole). Nearby adult storks were foraging to feed this year's

growing young

(see right) (Photo

20 - Foraging stork), and a flock

of 12 storks foraging for prey followed a tractor as it cut grass for hay (Photo

21 - Storks foraging behind tractor). We

followed the Geological Trail which looped around on a board-walk among wide

sink holes clustered in the woodland. Again the depressions showed how close to

the ground surface the strata of gypsum and dolomite limestone lay. Back to the

parking area, we set a course north on Route 190 towards the Latvian border in

search of some the other Karst features we had been told about (click

here for detailed map of route). The road led past modern farms with

dairy cattle and arable crops, but the agricultural countryside was also dotted

with the decaying concrete remains of collective farms from the period of Soviet

occupation. The current day more affluent-looking farms showed clearly how much

more productive the land use now was compared with the communist era enforced

collectivization. Reaching the border at Germaniškis village, the main road went

ahead to the border-crossing into Latvia; we turned off onto a very dusty gravel

road which followed the limestone strata just below the surface soil (see left) (Photo

19 - Geologists' sink hole). Nearby adult storks were foraging to feed this year's

growing young

(see right) (Photo

20 - Foraging stork), and a flock

of 12 storks foraging for prey followed a tractor as it cut grass for hay (Photo

21 - Storks foraging behind tractor). We

followed the Geological Trail which looped around on a board-walk among wide

sink holes clustered in the woodland. Again the depressions showed how close to

the ground surface the strata of gypsum and dolomite limestone lay. Back to the

parking area, we set a course north on Route 190 towards the Latvian border in

search of some the other Karst features we had been told about (click

here for detailed map of route). The road led past modern farms with

dairy cattle and arable crops, but the agricultural countryside was also dotted

with the decaying concrete remains of collective farms from the period of Soviet

occupation. The current day more affluent-looking farms showed clearly how much

more productive the land use now was compared with the communist era enforced

collectivization. Reaching the border at Germaniškis village, the main road went

ahead to the border-crossing into Latvia; we turned off onto a very dusty gravel

road which followed the

meandering course of the border river. We had been given

the locations of dolomite limestone outcrops along the river, where the river's

embankment revealed these exposed features of the Karstic landscape. We bumped

along the gravel road for 3kms just on the Lithuanian side of the river bank,

reaching the turning to the first outcrop at the Vilniapilis Cave. But in this

afternoon's hot temperatures, there was neither time nor inclination to walk the

2kms of footpath to find the cave. We continued along the gravel road, and by a meandering course of the border river. We had been given

the locations of dolomite limestone outcrops along the river, where the river's

embankment revealed these exposed features of the Karstic landscape. We bumped

along the gravel road for 3kms just on the Lithuanian side of the river bank,

reaching the turning to the first outcrop at the Vilniapilis Cave. But in this

afternoon's hot temperatures, there was neither time nor inclination to walk the

2kms of footpath to find the cave. We continued along the gravel road, and by a farmstead paused to photograph a stork's nest with 3 chicks awaiting the return

of the parent bird bringing food (see left) (Photo

22 - Stork chicks on nest).

For over a month now since Northern Poland, we had regularly been seeing both

adult storks incubating eggs and newly hatched chicks already growing. Reaching

the Lithuanian border village of Nemunėlio Radviliškis, there was no

border-crossing over the river but the gravel lane curved along the border on

the Lithuanian side. By a Lithuanian border-marker, wooden steps descended

steeply to the river bank where erosion had exposed a 4m high wall of the

Muoriškiai outcropping dolomite. Interesting as it was however, it scarcely

seemed worth the distance we had driven on dusty gravel roads to find it!

farmstead paused to photograph a stork's nest with 3 chicks awaiting the return

of the parent bird bringing food (see left) (Photo

22 - Stork chicks on nest).

For over a month now since Northern Poland, we had regularly been seeing both

adult storks incubating eggs and newly hatched chicks already growing. Reaching

the Lithuanian border village of Nemunėlio Radviliškis, there was no

border-crossing over the river but the gravel lane curved along the border on

the Lithuanian side. By a Lithuanian border-marker, wooden steps descended

steeply to the river bank where erosion had exposed a 4m high wall of the

Muoriškiai outcropping dolomite. Interesting as it was however, it scarcely

seemed worth the distance we had driven on dusty gravel roads to find it!

Yet another WW2 German atrocity:

turning back into Nemunėlio Radviliškis, a brown sign pointed to the site

of WW2 Jewish mass murders by German troops in the nearby forests. After

following the path however for over a kilometre into the pine forest, we had

found no memorial, and had now run out of time; the dark forests would keep

their hidden secrets of the evil events of August 1941, when German

einsatzgruppe killing squads, following on behind the Wehrmacht invasion of

the Baltic States, had murdered the village's 80 strong Jewish population, men

women and children, in the neighbouring forests. Such mass killings of Jews by

the German invaders were systematically repeated at a total of 258 towns and villages across Lithuania. Let us not air-brush out

of historical narrative who actually

committed such atrocities, by einsatzgruppe killing squads, following on behind the Wehrmacht invasion of

the Baltic States, had murdered the village's 80 strong Jewish population, men

women and children, in the neighbouring forests. Such mass killings of Jews by

the German invaders were systematically repeated at a total of 258 towns and villages across Lithuania. Let us not air-brush out

of historical narrative who actually

committed such atrocities, by making politically correct, sanitised reference to

Nazis, as if these were some distinct and anonymous microcosm; let us

instead be brutally frank: we all know which European nation bears everlasting responsibility for the Holocaust.

making politically correct, sanitised reference to

Nazis, as if these were some distinct and anonymous microcosm; let us

instead be brutally frank: we all know which European nation bears everlasting responsibility for the Holocaust.

Visit to Rinkuškiai Brewery: it was

by now 4-25pm and we had 35 minutes to drive back to Biržai for our visit to Rinkuškiai

Brewery. We drove purposely back into the town, reaching the micro-brewery with

minutes to spare, and joined the group for the brewery tour. Rinkuškiai Brewery

was founded in 1991, starting from a small, family-run home-brewing concern to

develop into the successful enterprise of today, as one of Lithuania's largest

micro-breweries, building on Biržai's long-standing brewing heritage. They now

produce a wide range of both light and dark beers of outstanding quality as our

tasting proved. The

guide's commentary was in Lithuanian, but she gave a brief summary in English

for our benefit. We viewed the mash tuns, wort boiling coppers, steel fermenting vessels,

filtration plant and maturing vats, ending at the bottling plant and brewery

museum. At Rinkuškiai we had managed to pull off our first brewery

visit of this trip (see

left) (Photo

23 - Rinkuškiai Brewery). visit of this trip (see

left) (Photo

23 - Rinkuškiai Brewery).

A day in camp at Biržai Camping:

back at Biržai Camping, the site was busier and noisier tonight with groups of

summer weekenders, but we moved away from the worst of these closer to

reception, bringing us into range of the campsite wi-fi ready for our day in

camp here tomorrow. On the Sunday morning, most of the weekend campers left,

leaving us to enjoy a gloriously peaceful and productive afternoon of warm

sunshine under the dappled shade of the tall oak trees. And that evening after

supper, we walked around to the lake for photos of the sun declining behind Biržai's

long wooden footbridge (Photo

24 - Declining sun over Biržai footbridge) (see above right) and setting across the lake against the

silhouetted lake shore trees (see left) (Photo

25 - Sunset over Lake Šivėna). The setting sun's golden light somehow emphasised

the footbridge's length spanning lake Šivėna

(Photo

26 - Biržai footbridge at sunset).

Back at the campsite, the sunset after-glow still

gave a late golden lighting to the camper among the oak trees (Photo

27- Sunset after-glow at Biržai Camping). morning, most of the weekend campers left,

leaving us to enjoy a gloriously peaceful and productive afternoon of warm

sunshine under the dappled shade of the tall oak trees. And that evening after

supper, we walked around to the lake for photos of the sun declining behind Biržai's

long wooden footbridge (Photo

24 - Declining sun over Biržai footbridge) (see above right) and setting across the lake against the

silhouetted lake shore trees (see left) (Photo

25 - Sunset over Lake Šivėna). The setting sun's golden light somehow emphasised

the footbridge's length spanning lake Šivėna

(Photo

26 - Biržai footbridge at sunset).

Back at the campsite, the sunset after-glow still

gave a late golden lighting to the camper among the oak trees (Photo

27- Sunset after-glow at Biržai Camping).

Biržai Castle and War Memorial: the following morning, after our

memorable weekend stay at Biržai's delightful little campsite, we drove into

town and parked by the Castle. Nearby stood the Biržai Monument to those

killed in the 1917~20 Lithuanian War of Independence (Photo

28 - Independence War Memorial). The original red granite statue of a

grieving mother was created by sculptor Robertas Antinis in 1931. In 1945 the

Soviets destroyed the original monument to make way for the Red Army military

cemetery. The buried fragments of the statue were used by Antinis' artist son to

re-create a copy of the original monument

which now stands by the memorial

gardens, with a large section of the original now under a wooden canopy set

alongside. The Castle's scant remains are approached across a sturdy draw-bridge

over the dry moat and beyond the surrounding rampart walls, the vista opened up

across parkland of the reconstructed palace which now stands by the memorial

gardens, with a large section of the original now under a wooden canopy set

alongside. The Castle's scant remains are approached across a sturdy draw-bridge

over the dry moat and beyond the surrounding rampart walls, the vista opened up

across parkland of the reconstructed palace  (see above right) (Photo

29 - Biržai Castle). (see above right) (Photo

29 - Biržai Castle).

Kirkilai Viewing Tower over Karst Lakes:

before leaving Biržai, we drove to the farming hamlet of Kirkilai where an

extensive area of sink holes has flooded to form a series of Karst lakes. At the

edge of the village, an upright crescent-shaped 32m high viewing tower has been

constructed overlooking the lakeland. Although a well-known local attraction

bringing hordes of visitors to the village, we feared that such an incongruous

structure, visible for miles around in the flat countryside, would form an alien

intrusion into the natural landscape. 1km along a dusty gravel road, we reached

the tower, and in fact, despite its huge height, when close up its natural wood

facing helped it to blend into the landscape and surrounding trees (see above

left) (Photo

30 - Kirkilai Viewing Tower). Overwhelmed with visitors at the weekend, on a

Monday morning the car park was deserted. At almost 100 feet up its lattice

metal steps, today's wind whistled around the tower, an unnerving climb but giving exhilarating views