|

CAMPING

IN FINLAND and LAPLAND 2012 - North Karelia, Kainuu, easternmost point of Finland/EU, and

bear-watching at the Russian border: CAMPING

IN FINLAND and LAPLAND 2012 - North Karelia, Kainuu, easternmost point of Finland/EU, and

bear-watching at the Russian border:

Our last news report from Finland was dated 24 July at Joensuu,

and since then the whole of our time within Finland, Lapland and Arctic Norway has been

so filled with unprecedented travel experiences and learning that our customary

practice of publishing 2-weekly editions of web-updates has perforce had to be

abandoned in favour of retrospective reporting. This unforgivable break with

tradition will not have gone unnoticed by regular readers, some of whom have

been kind enough to email with expressions of concern as to our whereabouts.

With apologies for the hiatus, we shall now pick up again and resume the account

of our journey up through Eastern Finland, with the promise of continuity of

regular reports for what has been the most satisfyingly rewarding of trips.

The morning we left Joensuu, we

discovered its best feature - Route 6 northwards out of town. Beyond Eno, we

turned off eastwards passing more anti-tank stone obstacles of the WW2 Salpa

Defensive Line on lonely Route 514 through deserted forested countryside to

reach Ilomantsi. This easternmost municipality of Finland still has a

significant Orthodox population reflecting its Russian history and its own

Karelian dialect. People still refer to the village not by the Finnish word kylä

but the Russian loan-word pogost; even the local newspaper is called Pogostam Sanomat. The Ilomantsi TIC is operated by a private

concern, Karelia Expert Oy and was impressively helpful, providing not only

local information but also brochures on distant areas and a detailed map for our

visit to the Petkeljärvi National Park and eastern border region.

|

Click on the 3 areas of map for

details of Eastern Finland and the Russian border |

|

Set on a hillside just outside Ilomantsi, the

so-called bardic village of Parppeinvaara preserves a collection of traditional

wooden Karelian rural buildings (Photo 1 - Karelian wooden cottage at Parppeinvaara), and is named after a local 19th century

bard-singer and player of the kantele stringed zither-like folk instrument whose oral tradition verses inspired the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala -

more of that later. The bardic-village was all rather low-key and we were about

to give up on it as something of a tourist trap, albeit deserted today, but the

museum proved the highlight of an otherwise unmemorable visit: a youngster in

Karelian dress not only played the kantele for us but sang traditional songs

accompanied by this beautiful instrument which we had seen last year in the

Baltic States but never before heard played. She was a student in

folk-music studies at Joensuu University and explained to us the history of 19th

century collection of traditional Karelian bardic songs (Photo 1 - Traditional Karelian bardic instrument, the Kantele, played at Parppeinvaara). Set on a hillside just outside Ilomantsi, the

so-called bardic village of Parppeinvaara preserves a collection of traditional

wooden Karelian rural buildings (Photo 1 - Karelian wooden cottage at Parppeinvaara), and is named after a local 19th century

bard-singer and player of the kantele stringed zither-like folk instrument whose oral tradition verses inspired the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala -

more of that later. The bardic-village was all rather low-key and we were about

to give up on it as something of a tourist trap, albeit deserted today, but the

museum proved the highlight of an otherwise unmemorable visit: a youngster in

Karelian dress not only played the kantele for us but sang traditional songs

accompanied by this beautiful instrument which we had seen last year in the

Baltic States but never before heard played. She was a student in

folk-music studies at Joensuu University and explained to us the history of 19th

century collection of traditional Karelian bardic songs (Photo 1 - Traditional Karelian bardic instrument, the Kantele, played at Parppeinvaara).

Late afternoon we drove out eastwards along

Route 500 through the forested wilds to find the Petkeljärvi National Park

Information Centre. The small camping area in a pine woods clearing was to be

our base for the next 3 days despite the horrendous midges; the national park

warden was welcoming and provided us with details of walking routes. BBQ-ing

supper wearing a midge-net helmet was a novel experience

The following day, with exposed flesh liberally

smeared with DEET against the midges, we set out on one of Petkeljärvi's

way-marked walking trails, which threaded its way along the spectacularly narrow

wooded crest of a classic esker-ridge between 2 of the lakes (Photo 3 - Esker glacial-ridge

in Petkeljärvi National Park). Both sides of the

ridge dropping away steeply to lake level were covered with bright green-leafed

bilberry, spiky crowberry and leathery-leafed lingonberry, and peppered with

white Labrador-tea flowers. We continued southwards along the high crest of the

esker-ridge, passing frequent remains of wartime Finnish defensive trenches and

gun emplacements. The path followed the line of the ridge which tapered down

gradually losing height to the very tip of the esker, ending at a

watery gap beyond which the esker continued southwards (Photo 4 - Tapering end of Petkeljärvi esker-ridge). The ground at the esker

tip was covered with beautiful pink-fringed white bog-bilberry flowers (Photo

5 - Flowers of Bog-Bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum)); we

were so looking forward to the berry picking season in a couple of months. On

the return walk along the narrow ridge, the sky cleared to give perfect light

for photographing the esker, the wooded sides falling steeply down to the lake

on both sides. It was like walking between the pages of a geology text book,

witnessing at close hand such perfect esker topography. And part way along, we

heard the characteristic plaintive wailing shriek echoing across the lake of the

Black Throated Diver whose image forms the Petkeljärvi National Park emblem (see

left) in Petkeljärvi National Park). Both sides of the

ridge dropping away steeply to lake level were covered with bright green-leafed

bilberry, spiky crowberry and leathery-leafed lingonberry, and peppered with

white Labrador-tea flowers. We continued southwards along the high crest of the

esker-ridge, passing frequent remains of wartime Finnish defensive trenches and

gun emplacements. The path followed the line of the ridge which tapered down

gradually losing height to the very tip of the esker, ending at a

watery gap beyond which the esker continued southwards (Photo 4 - Tapering end of Petkeljärvi esker-ridge). The ground at the esker

tip was covered with beautiful pink-fringed white bog-bilberry flowers (Photo

5 - Flowers of Bog-Bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum)); we

were so looking forward to the berry picking season in a couple of months. On

the return walk along the narrow ridge, the sky cleared to give perfect light

for photographing the esker, the wooded sides falling steeply down to the lake

on both sides. It was like walking between the pages of a geology text book,

witnessing at close hand such perfect esker topography. And part way along, we

heard the characteristic plaintive wailing shriek echoing across the lake of the

Black Throated Diver whose image forms the Petkeljärvi National Park emblem (see

left)

Despite the ferocious midges (even lighting the

supper barbecue meant wearing a midge-helmet),

the Petkeljärvi Information Centre had been a memorable place to camp with

welcoming warden and excellent facilities, and we spent a day in camp catching

up with jobs and updating the web site in the forest clearing with sunlight

filtering down through the 120 feet high ancient pines under which we were

camped. Returning along the lane under the towering pines to Route 500, we turned along to Möhkö, a scattered village close to the

Russian border. A peaceful place now, in the late 19th century it was a major

industrial centre of iron production. A small museum gave the history of the

development and decline of smelting at the Möhkö iron works deep in the forests.

Uniquely iron ore here was not mined but dredged from lakes and swamps. Iron

compounds leached from the bed rock was precipitated onto gravel on lake beds to

form large granules or coin-shaped nodules of 'lake iron'; we were able to

handle samples of such heavy rust-coloured lake ore at the museum. Industrial

scale smelting developed at Möhkö with the fast-flowing river driving

water-mills to power huge blast furnaces. Lake iron working continued until 1908

but with the invention of dynamite making possible large scale mining of ore,

extraction of lake ore became uneconomic and the Möhkö iron works closed with

timber logging taking over as the local industry. On a lovely sunny morning we walked among the remains of the iron works and its blast furnace kilns

alongside the canal, a fascinating piece of Eastern

Finland's industrial history. Despite the ferocious midges (even lighting the

supper barbecue meant wearing a midge-helmet),

the Petkeljärvi Information Centre had been a memorable place to camp with

welcoming warden and excellent facilities, and we spent a day in camp catching

up with jobs and updating the web site in the forest clearing with sunlight

filtering down through the 120 feet high ancient pines under which we were

camped. Returning along the lane under the towering pines to Route 500, we turned along to Möhkö, a scattered village close to the

Russian border. A peaceful place now, in the late 19th century it was a major

industrial centre of iron production. A small museum gave the history of the

development and decline of smelting at the Möhkö iron works deep in the forests.

Uniquely iron ore here was not mined but dredged from lakes and swamps. Iron

compounds leached from the bed rock was precipitated onto gravel on lake beds to

form large granules or coin-shaped nodules of 'lake iron'; we were able to

handle samples of such heavy rust-coloured lake ore at the museum. Industrial

scale smelting developed at Möhkö with the fast-flowing river driving

water-mills to power huge blast furnaces. Lake iron working continued until 1908

but with the invention of dynamite making possible large scale mining of ore,

extraction of lake ore became uneconomic and the Möhkö iron works closed with

timber logging taking over as the local industry. On a lovely sunny morning we walked among the remains of the iron works and its blast furnace kilns

alongside the canal, a fascinating piece of Eastern

Finland's industrial history.

Returning to Ilomantsi (pronounced with the stress

on the first syllable), we topped up our provisions at the S-Market supermarket

and arranged to meet the Orthodox priest's wife for us see the Church of Elijah

the Prophet which this year was celebrating its 125th anniversary

(Photo 6 - Russian Orthodox church at Ilomantsi ). The ochre

coloured church with its green domes and gilded baubles housed one particular

treasure, the Icon of the Tikhin Virgin brought from Russia

(Photo 7 - Icons in Ilomantsi Orthodox church). We tried also to

visit Ilomantsi's Lutheran Church built by the Swedes when they colonised this

area in the 18th century. They had attempted to convert the predominantly

Orthodox population by decorating the church interior with inspirational painted

images of angels, giving the church its name of the Church of 100 Angels. Today

no one was available to open the church for us, so we were unable to see the

pictorial results of Lutheran proselytising zeal. Instead we wandered among the

old Orthodox midge-infested graves down by the lakeside and found the war cemetery where the dead from the 1939~44 Winter and Continuation Wars are

commemorated.

cemetery where the dead from the 1939~44 Winter and Continuation Wars are

commemorated.

Passing the railway station where wagons loaded

with timber from the local forests filled the sidings, we left Ilomantsi to

continue northwards on Route 522 to Hattuvaara, Finland's most easterly village.

We camped for a couple of nights at Hattuvaara in the car park of the

distinctive grey wooden building of Taistelijan Talo (Fighters' House) built

originally as a memorial to those who had defended Finland against Soviet

aggression in 1939~44 (Photo 8 - Taistelijan Talo (Fighters' House) at Hattuvaara village). As well as having a small WW2 museum, the place now

functions as a restaurant owned by the same personality-challenged individual

described by Margaret and Barry Williamson in the account of their visit in 2010

(Magbaz Travels).

He was with some difficulty made to understand that in return for paying to camp

in his car park, we expected access to toilet and showers; he eventually opened

up the basement facilities in his WW2 museum, and it was a novel experience

washing up amid racks of machine guns and, on entering the toilets, being greeted in the semi-darkness by

a mannequin pointing his rifle!

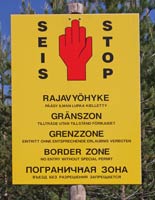

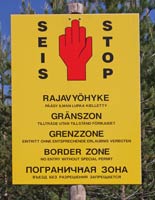

Our reason for staying at Hattuvaara was in order

to visit Finland's and mainland EU's easternmost point, 18 kms along a lonely

gravelled lane leading to the Finnish~Russian border. Until recently you needed

to obtain a border pass from the border guards' post in Hattuvaara to travel out

to this point in the patrolled border zone. We were assured that the border pass

requirement had now been dropped, and with some uncertainty set off along the

dusty lane through the forest (Photo 9 - Forest dirt-road leading to Finland/EU's easternmost point) with our satnav set at N 62.90947 E 31.58114,

passing on the way several blue EU signs at crucial junctions. Some 3kms from

the border the former control barrier now lay on the ground, but yellow-topped

posts indicated we had now entered the border zone and very formally worded

signs warned that leaving the road was forbidden without a pass. The lane ended

at a small car park from where a board-walk path led a further 200m to a wooden

platform at the water's edge of Lake Virmajärvi, with rope barriers marking the

forbidden entry border zone (Photo 10 - Boardwalk to easternmost point border-zone). A wooden marker post indicated the accessible point

of Suomen ja Euroopan Unionin Mantereen itäisin piste (Finland and EU

Easternmost Point), but 150m out on an islet in the lake, official border posts

(blue and white for Finland - red and green for the Russian Federation) marked

the actual line of the border, defined southwards by the 1940 Treaty of Moscow

and northwards by the 1617 Treaty of Stolbov (Photo 11 - Easternmost point of Finland and Mainland EU at Russian border). This was the furthest east we had

stood in mainland Europe, further east than Narva in Estonia, the Thracian~Turkish

border on the River Evros in Northern Greece or the Croat~Serbian border in

Eastern Slavonia. Today we had this curious spot to ourselves, seeing no sign of

the Finnish border guards who previously inspected passes as they patrolled the

border zone. leading to Finland/EU's easternmost point) with our satnav set at N 62.90947 E 31.58114,

passing on the way several blue EU signs at crucial junctions. Some 3kms from

the border the former control barrier now lay on the ground, but yellow-topped

posts indicated we had now entered the border zone and very formally worded

signs warned that leaving the road was forbidden without a pass. The lane ended

at a small car park from where a board-walk path led a further 200m to a wooden

platform at the water's edge of Lake Virmajärvi, with rope barriers marking the

forbidden entry border zone (Photo 10 - Boardwalk to easternmost point border-zone). A wooden marker post indicated the accessible point

of Suomen ja Euroopan Unionin Mantereen itäisin piste (Finland and EU

Easternmost Point), but 150m out on an islet in the lake, official border posts

(blue and white for Finland - red and green for the Russian Federation) marked

the actual line of the border, defined southwards by the 1940 Treaty of Moscow

and northwards by the 1617 Treaty of Stolbov (Photo 11 - Easternmost point of Finland and Mainland EU at Russian border). This was the furthest east we had

stood in mainland Europe, further east than Narva in Estonia, the Thracian~Turkish

border on the River Evros in Northern Greece or the Croat~Serbian border in

Eastern Slavonia. Today we had this curious spot to ourselves, seeing no sign of

the Finnish border guards who previously inspected passes as they patrolled the

border zone.

Returning slowly along the lonely dirt-road

raising clouds of dust behind us, we paused in Hattuvaara at the remarkably

well-stocked kylä-kauppa (village shop) for a few food items, arousing much

curiosity from the group of elderly locals sat drinking coffee. Nearby the

village's small Orthodox chapel (tsasouma), said to be the oldest in Finland

built in 1790, was surrounded by delightful flower gardens (Photo 12 - Orthodox

Chapel (tsasouma) at

Hattuvaara). The chapel was unfortunately

locked but a poster advertised the forthcoming festival of Petrun on 29 June

with its traditional Praasniekka procession. Back in camp at the Fighters' House

car park, we chatted with the charming Estonian lady who was running the

restaurant's catering; she was pleasantly surprised to hear that last year we

had visited her home city of Tartu in southern Estonia and proudly told us she

had sung in the song festival there. Returning slowly along the lonely dirt-road

raising clouds of dust behind us, we paused in Hattuvaara at the remarkably

well-stocked kylä-kauppa (village shop) for a few food items, arousing much

curiosity from the group of elderly locals sat drinking coffee. Nearby the

village's small Orthodox chapel (tsasouma), said to be the oldest in Finland

built in 1790, was surrounded by delightful flower gardens (Photo 12 - Orthodox

Chapel (tsasouma) at

Hattuvaara). The chapel was unfortunately

locked but a poster advertised the forthcoming festival of Petrun on 29 June

with its traditional Praasniekka procession. Back in camp at the Fighters' House

car park, we chatted with the charming Estonian lady who was running the

restaurant's catering; she was pleasantly surprised to hear that last year we

had visited her home city of Tartu in southern Estonia and proudly told us she

had sung in the song festival there.

The following morning, we continued north along

Route 522 through desolately empty forested terrain stretching away in all

directions as far as the eye could see, with not even an isolated farmstead in

sight. By cleared areas of forest, great heaps of cut timber were stacked by the roadside drying or awaiting collection; back in Hattuvaara, the only

traffic passing our camp had been the occasional timber truck. Despite being

designated as the Via Karelia, Route 522's tarmac soon ended and we made slower

progress for the next 30kms along gravelled surface until the asphalt began

again after crossing the Lieksa district's border. Beyond here we reached the

crucial turning for our next stop, the Patvinsuo National Park. A further short

stretch of dirt road led to the national park's Information Centre where the

helpful warden provided details of local walks and readily agreed to our

wild-camping that night in the pleasant grassy clearing by the centre. That

afternoon, again well-doused with DEET as protection against the midges, we

walked the Patvinsuo Mäntypolku nature trail, a way-marked circuit through pine

and spruce woodland and along lake shores with the path lined with beautiful

Lingonberry flowers (Photo 13 - Lingonberry flowers - Vaccinium vitis-idaea). The route continued across bogland on sturdy board-walks

and here we found today's floral treasure, flourishing clumps of Cloudberry with

their large strawberry-like leaves and delicate white flowers which shed their

petals when you simply pointed a camera at them; again we were looking

forward to August to taste the orange cloudberry fruit (Photo 14 -

Cloudberry flowers - Rubus chamaemorus at Patvinsuo). Along this stretch we

also found beautiful specimens of Bog-rosemary with their elegant pink-tinged

globular flowers (Photo 15 - Bog Rosemary (Andromeda polifolia) at Patvinsuo). That evening's wild-camp, without power for our faithful

insect-repellent Bagon-vaporiser,

meant a trying time with midges; the only consolation was the sweet scent of

wild Lilies of the Valley wafting over. treasure, flourishing clumps of Cloudberry with

their large strawberry-like leaves and delicate white flowers which shed their

petals when you simply pointed a camera at them; again we were looking

forward to August to taste the orange cloudberry fruit (Photo 14 -

Cloudberry flowers - Rubus chamaemorus at Patvinsuo). Along this stretch we

also found beautiful specimens of Bog-rosemary with their elegant pink-tinged

globular flowers (Photo 15 - Bog Rosemary (Andromeda polifolia) at Patvinsuo). That evening's wild-camp, without power for our faithful

insect-repellent Bagon-vaporiser,

meant a trying time with midges; the only consolation was the sweet scent of

wild Lilies of the Valley wafting over.

We resumed our northward journey along Route 522, diverting into Lieksa, a small

town set on the shore of the huge Lake Pielinen, to re-stock with provisions;

the entire town population seemed gathered at the supermarket, attracted perhaps

by the free coffee and cakes. Even the midges of Patvinsuo were preferable to

such crowds and we beat a hasty retreat to find rural solitude again, this time

in the Ruunaa Trekking Area. This extensive tract of pathless wilderness

spanning the Finnish~Russian border is crossed by the mighty River Lieksanjoki

which zigzags a winding course from across in Russia passing through a sequence

of linear lakes and between these a series of 6 spectacular white-water rapids

before finally flowing into the Pielinen waterway. Our camp for the next few

days was at the Ruunaa

Retkeily Keskus (Trekking Centre). A board-walk led

from the well-laid out camping area down to a major set of rapids, Neitikoski,

where the wide river's foaming current, flowing at a formidable rate, spilled

over into the most horrendous set of rapids with the white water boiling up into

a swelling and churning mass. Did foolhardy souls really attempt to negotiate

such a maelstrom in canoes? The following morning we learnt that the answer was

Yes! Returning down to the water's edge to photograph the surging rapids in

bright sunlight, we witnessed brave canoeists paddling into the heart of the

rapids and skilfully riding the crest of the churning white-water; it was an

unbelievably impressive performance (Photo 16 - Canoeist on Neitikoski rapids on Lieksanjoki river). Our pursuits were however more mundane and

we set off to follow marked walking trails along the river banks past more of

the Ruunaa rapids between the lakes. From a wooden footbridge at a point where

the fast-flowing waters were channelled into a narrow gullet, we had a bird's

eye view of the rapids (Photo 17 - Rapids on Lieksanjoki river in Ruunaa Trekking Area). The path followed the river bank and negotiated marshy

areas on board-walks lined with a treasure trove of botanical gems like

Cloudberry and Cranberry flowers (Photo 18 - Cranberry flowers - Vaccinium oxycoccus) at Ruunaa) and

the first of this year's berries, Crowberries still green and unripe

(Photo 19 - Green, unripe Crowberries - Empetrium nigrum), providing us with a rival attraction to the

rapids

(Photo 20 - Board-walks crossing marshy land in Ruunaa Trekking Area). Retkeily Keskus (Trekking Centre). A board-walk led

from the well-laid out camping area down to a major set of rapids, Neitikoski,

where the wide river's foaming current, flowing at a formidable rate, spilled

over into the most horrendous set of rapids with the white water boiling up into

a swelling and churning mass. Did foolhardy souls really attempt to negotiate

such a maelstrom in canoes? The following morning we learnt that the answer was

Yes! Returning down to the water's edge to photograph the surging rapids in

bright sunlight, we witnessed brave canoeists paddling into the heart of the

rapids and skilfully riding the crest of the churning white-water; it was an

unbelievably impressive performance (Photo 16 - Canoeist on Neitikoski rapids on Lieksanjoki river). Our pursuits were however more mundane and

we set off to follow marked walking trails along the river banks past more of

the Ruunaa rapids between the lakes. From a wooden footbridge at a point where

the fast-flowing waters were channelled into a narrow gullet, we had a bird's

eye view of the rapids (Photo 17 - Rapids on Lieksanjoki river in Ruunaa Trekking Area). The path followed the river bank and negotiated marshy

areas on board-walks lined with a treasure trove of botanical gems like

Cloudberry and Cranberry flowers (Photo 18 - Cranberry flowers - Vaccinium oxycoccus) at Ruunaa) and

the first of this year's berries, Crowberries still green and unripe

(Photo 19 - Green, unripe Crowberries - Empetrium nigrum), providing us with a rival attraction to the

rapids

(Photo 20 - Board-walks crossing marshy land in Ruunaa Trekking Area). After such a rewarding time at Ruunaa, we

continued north on traffic-free Route 73 towards Nurmes. Founded in 1876 by Tsar

Alexander II at the NW tip of Lake Pielinen, Nurmes is a quiet and unassuming

little town which still shows its imperial Russian origins. The old part of the

town retains its original wooden houses built along a grid of streets across the

length of a steep-sided esker-ridge linking the 2 lakes of Nurmesjärvi and

Pielinen

(Photo 21 - Nurmes Old Town's Imperial Russian era wooden houses). We parked by the centre to wait for the TIC to open at 2-00pm. The

lady was delightfully helpful on practical issues such as location of

supermarkets and details of weather forecast, but seemed surprisingly reticent

when asked what she would advise we visit in Nurmes: well there was the Old Town

with its wooden houses, and ... yes the museum, ... but that was about it

really. What about the churches? we prompted; M'mm, the Orthodox Church is only

open by arrangement, and ... well, that was about it really. Believing there

must be more to Nurmes than that, we walked through the Old Town admiring the

wooden houses along Kirkkokato (Church Street) along the top of the esker, an

attractive avenue lined with birch trees. At the far end the esker-ridge tapered down through a formally laid-out war-cemetery from 1939~44, but scattered among

the trees were 19th century metal crosses marking the graves of those who had

died of starvation after failed harvests. The TIC lady's reticence was apt: when

you had seen the esker, birch-lined Kirkkokato and the Old Town's wooden houses,

that indeed was about all of Nurmes. But Nurmes' attractiveness was its modesty;

we liked it for that, and agreed with Rough Guide's description - a little gem.

The nearby over-promoted Bomba village, a reconstruction of a Karelian log

mansion up-sticked from Suojärvi now in Russia and reassembled here appealing to

the Finns' nostalgia for lost Karelia, was a sordidly over-commercialised hotel

complex, scarcely worth a glance. And the nearby Hyvärila Camping was a noise-ridden building

site, so overwhelmed by diggers and lorries that we demanded a refund; the girl

at reception did her best to be gracious saying she hoped we should return when

the work was finished; I doubt it was our departing response. asked what she would advise we visit in Nurmes: well there was the Old Town

with its wooden houses, and ... yes the museum, ... but that was about it

really. What about the churches? we prompted; M'mm, the Orthodox Church is only

open by arrangement, and ... well, that was about it really. Believing there

must be more to Nurmes than that, we walked through the Old Town admiring the

wooden houses along Kirkkokato (Church Street) along the top of the esker, an

attractive avenue lined with birch trees. At the far end the esker-ridge tapered down through a formally laid-out war-cemetery from 1939~44, but scattered among

the trees were 19th century metal crosses marking the graves of those who had

died of starvation after failed harvests. The TIC lady's reticence was apt: when

you had seen the esker, birch-lined Kirkkokato and the Old Town's wooden houses,

that indeed was about all of Nurmes. But Nurmes' attractiveness was its modesty;

we liked it for that, and agreed with Rough Guide's description - a little gem.

The nearby over-promoted Bomba village, a reconstruction of a Karelian log

mansion up-sticked from Suojärvi now in Russia and reassembled here appealing to

the Finns' nostalgia for lost Karelia, was a sordidly over-commercialised hotel

complex, scarcely worth a glance. And the nearby Hyvärila Camping was a noise-ridden building

site, so overwhelmed by diggers and lorries that we demanded a refund; the girl

at reception did her best to be gracious saying she hoped we should return when

the work was finished; I doubt it was our departing response.

Setting off northwards again on the quiet Route 75 through yet more forests, we

stopped to eat our sandwich lunch at a picnic area. Somehow this spot seemed to

epitomise the civility of life in Finland: they may have a high cost of living

and high taxation, but public money is spent well on first class public

services. As an example, this lay-by was provided with 2 sets of picnic tables,

one open-air, the other covered, and a set of WCs. As we eat our lunch, a truck

arrived and workmen began removing rubbish, picking up the small amount of

litter and cleaning the toilets. We had witnessed earlier in Nurmes another

example of Finland's caring society: on the counter at the bank, several sets of

reading glasses were available to help fill out forms. We have been so

comfortable in Finland as a truly enviable and civilised society; the comparison

with today's yobbish Western Europe goes without saying.

An hour's drive, passing from North Karelia into

the province of Kainuu, brought us to the outskirts of Kuhmo. Our reason for

coming to this quiet little logging town was to find the Juminkeko Centre, the

country's leading authority on everything to do with Finland's national epic,

the Kalevala. The Juminkeko Foundation is dedicated to the collection and

preservation of Karelian oral traditions of bardic folk-poetry and music which

had inspired the Kalevala's composition. Arriving at Juminkeko's modern

wooden building, we were given a knowledgeable background on Kalevala's

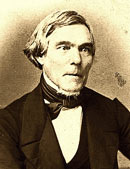

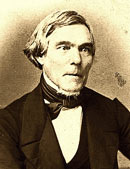

origins and its author Elias Lönnrot (1802~84). Lönnrot was a country doctor and

scholar from Helsinki who in the early 19th century made several expeditions

into the wilds of what is now Russian Karelia collecting and documenting the

ancient runic folk-poetry passed down by oral tradition and sung by bards often

accompanied by kantele music, the stringed zither like instrument we had heard

played at Parppeinvaara. Lönnrot assembled his collection of poetic material

into his own work which he entitled Kalevala. The first edition published

in 1835 was a conglomeration of collected material; in a second edition

published in 1849, the version of Kalevala read today as Finland's

national epic, Lönnrot rearranged his source material into a more coherent epic

tale; in his own words, he wanted to compile an epic half the size of Homer, and

it was - 22,750 lines of verse in 50 chapters. Set in an unspecified past age,

Kalevala's plot centres around the continuous wars between the mythical

land of Kalevala, often identified with Karelia, and Pohjola the land of the

North, over possession of a golden talisman called the Sampo. Many commentators

have interpreted this traditional folk-tale at the centre of Lönnrot's epic as a

symbolic representation of ancient territorial conflicts between the original

Finno-Ugric Sámi immigrants and later arriving Finns who pushed them northwards.

Lönnrot's compilation incorporates ancient creation myths, wedding songs, tales

of epic journeys, duals, spells, and fables of the struggle between good and

evil. The principle hero is Väinämöinen, a shamanistic wizard-like aged bard who

charms his opponents with his spells, incantations and kantele playing (see

picture right). The

epic poem tells the tale of his struggles and the many colourful figures he

encounters on his journeys. Kalevala concludes with Väinämöinen upstaged

by a counter-hero An hour's drive, passing from North Karelia into

the province of Kainuu, brought us to the outskirts of Kuhmo. Our reason for

coming to this quiet little logging town was to find the Juminkeko Centre, the

country's leading authority on everything to do with Finland's national epic,

the Kalevala. The Juminkeko Foundation is dedicated to the collection and

preservation of Karelian oral traditions of bardic folk-poetry and music which

had inspired the Kalevala's composition. Arriving at Juminkeko's modern

wooden building, we were given a knowledgeable background on Kalevala's

origins and its author Elias Lönnrot (1802~84). Lönnrot was a country doctor and

scholar from Helsinki who in the early 19th century made several expeditions

into the wilds of what is now Russian Karelia collecting and documenting the

ancient runic folk-poetry passed down by oral tradition and sung by bards often

accompanied by kantele music, the stringed zither like instrument we had heard

played at Parppeinvaara. Lönnrot assembled his collection of poetic material

into his own work which he entitled Kalevala. The first edition published

in 1835 was a conglomeration of collected material; in a second edition

published in 1849, the version of Kalevala read today as Finland's

national epic, Lönnrot rearranged his source material into a more coherent epic

tale; in his own words, he wanted to compile an epic half the size of Homer, and

it was - 22,750 lines of verse in 50 chapters. Set in an unspecified past age,

Kalevala's plot centres around the continuous wars between the mythical

land of Kalevala, often identified with Karelia, and Pohjola the land of the

North, over possession of a golden talisman called the Sampo. Many commentators

have interpreted this traditional folk-tale at the centre of Lönnrot's epic as a

symbolic representation of ancient territorial conflicts between the original

Finno-Ugric Sámi immigrants and later arriving Finns who pushed them northwards.

Lönnrot's compilation incorporates ancient creation myths, wedding songs, tales

of epic journeys, duals, spells, and fables of the struggle between good and

evil. The principle hero is Väinämöinen, a shamanistic wizard-like aged bard who

charms his opponents with his spells, incantations and kantele playing (see

picture right). The

epic poem tells the tale of his struggles and the many colourful figures he

encounters on his journeys. Kalevala concludes with Väinämöinen upstaged

by a counter-hero (whose mother had become pregnant by eating Lingonberries - be

warned!) and sailing off into the sunset leaving behind his kantele, with the

prophetic promise of "I shall return". (whose mother had become pregnant by eating Lingonberries - be

warned!) and sailing off into the sunset leaving behind his kantele, with the

prophetic promise of "I shall return".

Published at a time of the awakening of Finnish

awareness, Lönnrot's Kalevala gave inspiration to the Finnish Nationalist

movement and an influence to generations of Finnish artists, writers and

musicians, including of course Sibelius with his 1901 Karelia Suite and

Pohjola's Daughter (Daughter of the North) which accompanies this

edition. The

resemblance of plot and characters between Kalevala and Lord of the

Rings is also no coincidence: JRR Tolkien learnt Finnish in order to read

Kalevala and based the runic language of the Elves on Old Finnish. The yarn

of the Golden Ring with magical powers buried under a mountain echoes

Kalevala's Sampo talisman, and Gandalf the wise, old, spell-binding wizard

battling against evil is almost an exact plagiaristic recast of Lönnrot's

Väinämöinen.

At the Juminkeko Centre, in Kuhmo, we were shown

their collection of Kalevala translations into some 60 world-wide

languages. We learnt more of the background, plot and characters of the epic,

listened to part of an English rendering in the metre of Longfellow's Hiawatha,

and watched 2 of their excellent English-language films about Lönnrot's journeys

through Karelia collecting verses and the vagaries of Kalevala plot. The

Centre's Chairman, a gentle giant of a man, told us more about surviving

bard-singers still living in remote Karelian villages and even offered to

arrange for us to visit one. This had been a thoroughly educative visit, meeting

learned people and learning for ourselves much about Finland's still popular

national epic, another piece in the jigsaw of understanding the ethos of our

host country.

On the outskirts of Kuhmo, we found the Finnish

Large Carnivores Visitor Centre (Petola Luontokeskus) operated by Metsähallitus,

the Finnish National Forestry Agency whose comprehensive range of detailed

national park brochures had been such a help to us. The centre provides detailed

presentations of Finland's four surviving wild carnivores, the brown bear, lynx

wild-cat, wolf and wolverine,

a curious long-furred creature related to badgers

but resembling a small bear. We were late arriving but the girl helpfully stayed

on after official closing time to allow us time to study the excellent exhibits

and information panels. a curious long-furred creature related to badgers

but resembling a small bear. We were late arriving but the girl helpfully stayed

on after official closing time to allow us time to study the excellent exhibits

and information panels.

Kuhmo's over-promoted and over-priced

tourist attraction with the misnomer of 'Kalevala Village' has nothing to

do with the national epic; it is in fact nothing more than a Karelian theme

park; we imagined log-flumes, pine wood roller coasters and all the fun of a

money-spinning fair-ground, and gave the place a wide berth, moving on 15kms

north to find tonight's campsite. At Camping Lentuankosken Leirintä, we received

a warmly hospitable welcome from the family who own it. Despite being the

Midsummer holiday weekend, when Finns head out into the country to sit by a

lakeside, fishing and drinking beer, this remote campsite was peacefully quiet;

it was a delightful place to take a pause in our travels, and on this the

longest day of 2012, we photographed George our camper in perfect daylight at

10-30 in the evening (Photo 22 - Full daylight at 10-30 in the evening); in fact there had

not been a single moment of darkness during the whole trip so far. Much later that evening we

were treated to a fine sunset across the lake as wood smoke billowed from the

campsite's traditional lakeside smoke-sauna

(Photo 23 - Sunset over lake at Camping Lentuankosken).

We continued north making good progress through

North Kainuu on Route 912, a lonely road with surrounding forests stretching

away into the remote distance totally uninhabited other than a few isolated

farmsteads. Despite concerns about increased traffic over the holiday weekend,

out here in the remote uninhabited wilds of North Kainuu we passed virtually no

other vehicles. At one isolated hamlet, we paused at a little general stores cum

filling station for a few items of food; the shop was universally stocked with

foodstuffs, car parts and electrical goods. Life in these isolated areas must be

particularly tough, especially during the permanent darkness, lasting snow and

freezing temperatures of winter. This utterly deserted wilderness of endless

boreal coniferous forest was eerily unnerving, with a feeling of approaching

Lapland especially when we crossed a road-grid with a sign warning of entering

reindeer-herding territory.

As Route 912 approached Suomussalmi, we paused at

what seemed another WW2 monument with burnt out tanks and field guns rusting by

the road side. This was the Raatteen Portti (Raate Road) Museum, sited on one of

the main routes followed by the invading Red Army in November 1939 at the

outbreak of the Winter War. Fierce battles had been fought along the road in this

region, and despite heavy losses, the poorly equipped Finns had halted and

repulsed the invading Soviet tanks and heavy artillery during the harsh winter

of 1939~40. Just beyond the museum, a modern memorial took the form of 1000s of

scattered boulders symbolising the war dead; in the centre, a wooden trestle

monument named Avara Syli (Wide Embrace) looked out over the field of stones

hung with 105 bells which tinkled in the wind, one bell for each of the 105 days

that the Winter War lasted (Photo 24 - Stone-field Memorial to Winter War dead at Raatteen Portti). And as we walked back to our camper, we saw our

first reindeer casually trotting down the road, scampering off into the forest

at the approach of traffic (Photo 25 - Wild reindeer by roadside approaching Lapland). This sighting and the bitterly cold wind were

further reminders that we should soon be entering Lapland. As Route 912 approached Suomussalmi, we paused at

what seemed another WW2 monument with burnt out tanks and field guns rusting by

the road side. This was the Raatteen Portti (Raate Road) Museum, sited on one of

the main routes followed by the invading Red Army in November 1939 at the

outbreak of the Winter War. Fierce battles had been fought along the road in this

region, and despite heavy losses, the poorly equipped Finns had halted and

repulsed the invading Soviet tanks and heavy artillery during the harsh winter

of 1939~40. Just beyond the museum, a modern memorial took the form of 1000s of

scattered boulders symbolising the war dead; in the centre, a wooden trestle

monument named Avara Syli (Wide Embrace) looked out over the field of stones

hung with 105 bells which tinkled in the wind, one bell for each of the 105 days

that the Winter War lasted (Photo 24 - Stone-field Memorial to Winter War dead at Raatteen Portti). And as we walked back to our camper, we saw our

first reindeer casually trotting down the road, scampering off into the forest

at the approach of traffic (Photo 25 - Wild reindeer by roadside approaching Lapland). This sighting and the bitterly cold wind were

further reminders that we should soon be entering Lapland.

Approaching Suomussalmi, one of North kainuu's

main towns which had suffered badly from the German scorched earth policy in

their 1944 retreat from Finland, we turned northwards again onto Route 843. This

was an even more lonely road and for the next 30kms, we saw not one other vehicle.

An endless and deserted forested wilderness stretched away in all directions. We

reached our turning signed eastwards for 10kms along a dirt road to Pirttivaara

and the Martinselkosen Eräkeskus (Wilderness Centre), just 2 kms from the

Russian border. This is a commercial venture which for several years has

organised overnight safari-sessions in hides to watch wild Brown Bears which

still inhabit these remote forests. Our plan was to camp out here using the

centre's facilities and do some walking, but we were unsure about the

bear-watching given the high cost. When we arrived, that night's party of

bear-watchers were just gathering, and the following morning, we were woken by

them returning and talking excitedly about their overnight experiences of seeing

wild bears at close hand from the hides. Still uncertain about the cost, we

mulled over the bear-watching: it was a unique experience, and after talking it

over with the organisers, we were persuaded and signed on for that night's

session. Approaching Suomussalmi, one of North kainuu's

main towns which had suffered badly from the German scorched earth policy in

their 1944 retreat from Finland, we turned northwards again onto Route 843. This

was an even more lonely road and for the next 30kms, we saw not one other vehicle.

An endless and deserted forested wilderness stretched away in all directions. We

reached our turning signed eastwards for 10kms along a dirt road to Pirttivaara

and the Martinselkosen Eräkeskus (Wilderness Centre), just 2 kms from the

Russian border. This is a commercial venture which for several years has

organised overnight safari-sessions in hides to watch wild Brown Bears which

still inhabit these remote forests. Our plan was to camp out here using the

centre's facilities and do some walking, but we were unsure about the

bear-watching given the high cost. When we arrived, that night's party of

bear-watchers were just gathering, and the following morning, we were woken by

them returning and talking excitedly about their overnight experiences of seeing

wild bears at close hand from the hides. Still uncertain about the cost, we

mulled over the bear-watching: it was a unique experience, and after talking it

over with the organisers, we were persuaded and signed on for that night's

session. After a morning's walking in the

nearby forests, DEET-ed up and wearing midge-nets (Photo 26 - Midge-helmets necessary for forest walking), we prepared for our overnight

bear-watching, anticipating a long, cold and midge-ridden night, and at 4-00pm

the group gathered for briefing from Tuumpi our guide. We were transported in

4WD's several kms into the forests where border guards still patrolled perhaps

expecting a belated Russian invasion. A 1.5km walk further through the forest

and across swamps on board-walks brought us to the hides on a low hillock

overlooking a forest clearing. Earlier, staff from the centre had scattered

food, salmon fish and dog food pellets, to attract

bears. We settled into our

viewing places in the hides, positioning cameras and binoculars, and within a

half-hour the first bears appeared. From 5-30pm until gone midnight, we were

treated to a thrilling and at times comical 7½ hours of continuous

appearances of wild bears (Photo 27 - Wild Brown Bears in

Eastern Finland). They ranged in colour and size from a huge almost

black male, a number of smaller buff and chocolate-brown females, and up to six 18

month old cubs. The cubs wandered around sometimes singly, sometimes in

groups, but always warily looking around for adult bears. They entertainingly

stood up on back paws, and if an adult was spotted they scampered off or clawed

their way high into trees. It was almost like a choreographed series of

one-act drama: one or two bears would approach, pick at food or grub around under rocks for insects

then wander off, and after a while the next act would follow with

another group of bears entering at stage right. Through binoculars, we could see

clearly their huge claws and despite the bear fur's padded thickness, bears. We settled into our

viewing places in the hides, positioning cameras and binoculars, and within a

half-hour the first bears appeared. From 5-30pm until gone midnight, we were

treated to a thrilling and at times comical 7½ hours of continuous

appearances of wild bears (Photo 27 - Wild Brown Bears in

Eastern Finland). They ranged in colour and size from a huge almost

black male, a number of smaller buff and chocolate-brown females, and up to six 18

month old cubs. The cubs wandered around sometimes singly, sometimes in

groups, but always warily looking around for adult bears. They entertainingly

stood up on back paws, and if an adult was spotted they scampered off or clawed

their way high into trees. It was almost like a choreographed series of

one-act drama: one or two bears would approach, pick at food or grub around under rocks for insects

then wander off, and after a while the next act would follow with

another group of bears entering at stage right. Through binoculars, we could see

clearly their huge claws and despite the bear fur's padded thickness, midges

were buzzing around causing them to rub against rocks or scratch with their hind

paws. They seemed totally unaware of our presence and approached within 15 feet

of the hides, despite the constant clicking of camera shutters. We could see

their huge heads and jaws and actually hear their breathing and occasional

grunts. Late into the evening there was still sufficient light for photography

and in addition to watching the almost continuous display of bears feeding, we

were also treated to the rare spectacle of white-tailed eagles soaring overhead

and black kites swooping between trees. midges

were buzzing around causing them to rub against rocks or scratch with their hind

paws. They seemed totally unaware of our presence and approached within 15 feet

of the hides, despite the constant clicking of camera shutters. We could see

their huge heads and jaws and actually hear their breathing and occasional

grunts. Late into the evening there was still sufficient light for photography

and in addition to watching the almost continuous display of bears feeding, we

were also treated to the rare spectacle of white-tailed eagles soaring overhead

and black kites swooping between trees.

Although expensive, the venture was

well-organised: coffee and sandwiches were provided, and the hides were

well-appointed with comfortable viewing positions, and equipped with bunks and

sleeping bags for later when the last of the bears ambled away as the light

faded. The following morning we were woken at 6-30am; the new day's sun had been

up most of the night, and with all the food long gone there was no trace of the

bears as we emerged from the hides into the clearing. It was a curious sensation

standing outside the hides to take photos where last night the bears had

been feeding (Photo 28 - Martinselkosen Eräkeskus bear-watching hides). The only sign this morning of last evening's beers feeding was a few remaining fish bones.

After the return walk

through the forest, we were transported back to Martinselkosen for an early

breakfast.

After our extraordinarily thrilling night of

bear-watching, the morning's mundane jobs of preparing to move on seemed almost

surrealistic. Martinselkosen Eräkeskus had proved a worthy and welcoming place

to camp, and although the bear-watching had been expensive at €145 each, to have

missed this unique opportunity to see at first hand one of Europe's last

remaining wild carnivores would have been a lasting regret.

Visit the Martinselkosen web site for further details. As it was we had

a wealth of unbelievable memories of our night of watching wild brown bears at

close quarters, and hopefully a few reasonable photos to prove it, which we have

added as a separate gallery - see our

Brown Bear

Photo Gallery

Next week we continue ever northwards along the Via

Karelia to spend time at the Hossa Hiking Area and Oulanka National Park, and

cross the Arctic Circle into Lapland to visit Kemijärvi, Sodankylä and Ivalo.

Join us again shortly

Next edition

to be published in 2 weeks or so

|

Sheila and Paul |

Published: 18 October 2012 |

|

CAMPING

IN FINLAND and LAPLAND 2012 - North Karelia, Kainuu, easternmost point of Finland/EU, and

bear-watching at the Russian border:

CAMPING

IN FINLAND and LAPLAND 2012 - North Karelia, Kainuu, easternmost point of Finland/EU, and

bear-watching at the Russian border: Set on a hillside just outside Ilomantsi, the

so-called bardic village of Parppeinvaara preserves a collection of traditional

wooden Karelian rural buildings (Photo 1 - Karelian wooden cottage at Parppeinvaara), and is named after a local 19th century

bard-singer and player of the kantele stringed zither-like folk instrument whose oral tradition verses inspired the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala -

more of that later. The bardic-village was all rather low-key and we were about

to give up on it as something of a tourist trap, albeit deserted today, but the

museum proved the highlight of an otherwise unmemorable visit: a youngster in

Karelian dress not only played the kantele for us but sang traditional songs

accompanied by this beautiful instrument which we had seen last year in the

Baltic States but never before heard played. She was a student in

folk-music studies at Joensuu University and explained to us the history of 19th

century collection of traditional Karelian bardic songs (Photo 1 - Traditional Karelian bardic instrument, the Kantele, played at Parppeinvaara).

Set on a hillside just outside Ilomantsi, the

so-called bardic village of Parppeinvaara preserves a collection of traditional

wooden Karelian rural buildings (Photo 1 - Karelian wooden cottage at Parppeinvaara), and is named after a local 19th century

bard-singer and player of the kantele stringed zither-like folk instrument whose oral tradition verses inspired the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala -

more of that later. The bardic-village was all rather low-key and we were about

to give up on it as something of a tourist trap, albeit deserted today, but the

museum proved the highlight of an otherwise unmemorable visit: a youngster in

Karelian dress not only played the kantele for us but sang traditional songs

accompanied by this beautiful instrument which we had seen last year in the

Baltic States but never before heard played. She was a student in

folk-music studies at Joensuu University and explained to us the history of 19th

century collection of traditional Karelian bardic songs (Photo 1 - Traditional Karelian bardic instrument, the Kantele, played at Parppeinvaara). in Petkeljärvi National Park). Both sides of the

ridge dropping away steeply to lake level were covered with bright green-leafed

bilberry, spiky crowberry and leathery-leafed lingonberry, and peppered with

white Labrador-tea flowers. We continued southwards along the high crest of the

esker-ridge, passing frequent remains of wartime Finnish defensive trenches and

gun emplacements. The path followed the line of the ridge which tapered down

gradually losing height to the very tip of the esker, ending at a

watery gap beyond which the esker continued southwards (Photo 4 - Tapering end of Petkeljärvi esker-ridge). The ground at the esker

tip was covered with beautiful pink-fringed white bog-bilberry flowers (Photo

5 - Flowers of Bog-Bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum)); we

were so looking forward to the berry picking season in a couple of months. On

the return walk along the narrow ridge, the sky cleared to give perfect light

for photographing the esker, the wooded sides falling steeply down to the lake

on both sides. It was like walking between the pages of a geology text book,

witnessing at close hand such perfect esker topography. And part way along, we

heard the characteristic plaintive wailing shriek echoing across the lake of the

Black Throated Diver whose image forms the Petkeljärvi National Park emblem (see

left)

in Petkeljärvi National Park). Both sides of the

ridge dropping away steeply to lake level were covered with bright green-leafed

bilberry, spiky crowberry and leathery-leafed lingonberry, and peppered with

white Labrador-tea flowers. We continued southwards along the high crest of the

esker-ridge, passing frequent remains of wartime Finnish defensive trenches and

gun emplacements. The path followed the line of the ridge which tapered down

gradually losing height to the very tip of the esker, ending at a

watery gap beyond which the esker continued southwards (Photo 4 - Tapering end of Petkeljärvi esker-ridge). The ground at the esker

tip was covered with beautiful pink-fringed white bog-bilberry flowers (Photo

5 - Flowers of Bog-Bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum)); we

were so looking forward to the berry picking season in a couple of months. On

the return walk along the narrow ridge, the sky cleared to give perfect light

for photographing the esker, the wooded sides falling steeply down to the lake

on both sides. It was like walking between the pages of a geology text book,

witnessing at close hand such perfect esker topography. And part way along, we

heard the characteristic plaintive wailing shriek echoing across the lake of the

Black Throated Diver whose image forms the Petkeljärvi National Park emblem (see

left) Despite the ferocious midges (even lighting the

supper barbecue meant wearing a midge-helmet),

the Petkeljärvi Information Centre had been a memorable place to camp with

welcoming warden and excellent facilities, and we spent a day in camp catching

up with jobs and updating the web site in the forest clearing with sunlight

filtering down through the 120 feet high ancient pines under which we were

camped. Returning along the lane under the towering pines to Route 500, we turned along to Möhkö, a scattered village close to the

Russian border. A peaceful place now, in the late 19th century it was a major

industrial centre of iron production. A small museum gave the history of the

development and decline of smelting at the Möhkö iron works deep in the forests.

Uniquely iron ore here was not mined but dredged from lakes and swamps. Iron

compounds leached from the bed rock was precipitated onto gravel on lake beds to

form large granules or coin-shaped nodules of 'lake iron'; we were able to

handle samples of such heavy rust-coloured lake ore at the museum. Industrial

scale smelting developed at Möhkö with the fast-flowing river driving

water-mills to power huge blast furnaces. Lake iron working continued until 1908

but with the invention of dynamite making possible large scale mining of ore,

extraction of lake ore became uneconomic and the Möhkö iron works closed with

timber logging taking over as the local industry. On a lovely sunny morning we walked among the remains of the iron works and its blast furnace kilns

alongside the canal, a fascinating piece of Eastern

Finland's industrial history.

Despite the ferocious midges (even lighting the

supper barbecue meant wearing a midge-helmet),

the Petkeljärvi Information Centre had been a memorable place to camp with

welcoming warden and excellent facilities, and we spent a day in camp catching

up with jobs and updating the web site in the forest clearing with sunlight

filtering down through the 120 feet high ancient pines under which we were

camped. Returning along the lane under the towering pines to Route 500, we turned along to Möhkö, a scattered village close to the

Russian border. A peaceful place now, in the late 19th century it was a major

industrial centre of iron production. A small museum gave the history of the

development and decline of smelting at the Möhkö iron works deep in the forests.

Uniquely iron ore here was not mined but dredged from lakes and swamps. Iron

compounds leached from the bed rock was precipitated onto gravel on lake beds to

form large granules or coin-shaped nodules of 'lake iron'; we were able to

handle samples of such heavy rust-coloured lake ore at the museum. Industrial

scale smelting developed at Möhkö with the fast-flowing river driving

water-mills to power huge blast furnaces. Lake iron working continued until 1908

but with the invention of dynamite making possible large scale mining of ore,

extraction of lake ore became uneconomic and the Möhkö iron works closed with

timber logging taking over as the local industry. On a lovely sunny morning we walked among the remains of the iron works and its blast furnace kilns

alongside the canal, a fascinating piece of Eastern

Finland's industrial history.

cemetery where the dead from the 1939~44 Winter and Continuation Wars are

commemorated.

cemetery where the dead from the 1939~44 Winter and Continuation Wars are

commemorated.

leading to Finland/EU's easternmost point) with our satnav set at N 62.90947 E 31.58114,

passing on the way several blue EU signs at crucial junctions. Some 3kms from

the border the former control barrier now lay on the ground, but yellow-topped

posts indicated we had now entered the border zone and very formally worded

signs warned that leaving the road was forbidden without a pass. The lane ended

at a small car park from where a board-walk path led a further 200m to a wooden

platform at the water's edge of Lake Virmajärvi, with rope barriers marking the

forbidden entry border zone (Photo 10 - Boardwalk to easternmost point border-zone). A wooden marker post indicated the accessible point

of Suomen ja Euroopan Unionin Mantereen itäisin piste (Finland and EU

Easternmost Point), but 150m out on an islet in the lake, official border posts

(blue and white for Finland - red and green for the Russian Federation) marked

the actual line of the border, defined southwards by the 1940 Treaty of Moscow

and northwards by the 1617 Treaty of Stolbov (Photo 11 - Easternmost point of Finland and Mainland EU at Russian border). This was the furthest east we had

stood in mainland Europe, further east than Narva in Estonia, the Thracian~Turkish

border on the River Evros in Northern Greece or the Croat~Serbian border in

Eastern Slavonia. Today we had this curious spot to ourselves, seeing no sign of

the Finnish border guards who previously inspected passes as they patrolled the

border zone.

leading to Finland/EU's easternmost point) with our satnav set at N 62.90947 E 31.58114,

passing on the way several blue EU signs at crucial junctions. Some 3kms from

the border the former control barrier now lay on the ground, but yellow-topped

posts indicated we had now entered the border zone and very formally worded

signs warned that leaving the road was forbidden without a pass. The lane ended

at a small car park from where a board-walk path led a further 200m to a wooden

platform at the water's edge of Lake Virmajärvi, with rope barriers marking the

forbidden entry border zone (Photo 10 - Boardwalk to easternmost point border-zone). A wooden marker post indicated the accessible point

of Suomen ja Euroopan Unionin Mantereen itäisin piste (Finland and EU

Easternmost Point), but 150m out on an islet in the lake, official border posts

(blue and white for Finland - red and green for the Russian Federation) marked

the actual line of the border, defined southwards by the 1940 Treaty of Moscow

and northwards by the 1617 Treaty of Stolbov (Photo 11 - Easternmost point of Finland and Mainland EU at Russian border). This was the furthest east we had

stood in mainland Europe, further east than Narva in Estonia, the Thracian~Turkish

border on the River Evros in Northern Greece or the Croat~Serbian border in

Eastern Slavonia. Today we had this curious spot to ourselves, seeing no sign of

the Finnish border guards who previously inspected passes as they patrolled the

border zone. Returning slowly along the lonely dirt-road

raising clouds of dust behind us, we paused in Hattuvaara at the remarkably

well-stocked kylä-kauppa (village shop) for a few food items, arousing much

curiosity from the group of elderly locals sat drinking coffee. Nearby the

village's small Orthodox chapel (tsasouma), said to be the oldest in Finland

built in 1790, was surrounded by delightful flower gardens (Photo 12 - Orthodox

Chapel (tsasouma) at

Hattuvaara). The chapel was unfortunately

locked but a poster advertised the forthcoming festival of Petrun on 29 June

with its traditional Praasniekka procession. Back in camp at the Fighters' House

car park, we chatted with the charming Estonian lady who was running the

restaurant's catering; she was pleasantly surprised to hear that last year we

had visited her home city of Tartu in southern Estonia and proudly told us she

had sung in the song festival there.

Returning slowly along the lonely dirt-road

raising clouds of dust behind us, we paused in Hattuvaara at the remarkably

well-stocked kylä-kauppa (village shop) for a few food items, arousing much

curiosity from the group of elderly locals sat drinking coffee. Nearby the

village's small Orthodox chapel (tsasouma), said to be the oldest in Finland

built in 1790, was surrounded by delightful flower gardens (Photo 12 - Orthodox

Chapel (tsasouma) at

Hattuvaara). The chapel was unfortunately

locked but a poster advertised the forthcoming festival of Petrun on 29 June

with its traditional Praasniekka procession. Back in camp at the Fighters' House

car park, we chatted with the charming Estonian lady who was running the

restaurant's catering; she was pleasantly surprised to hear that last year we

had visited her home city of Tartu in southern Estonia and proudly told us she

had sung in the song festival there. treasure, flourishing clumps of Cloudberry with

their large strawberry-like leaves and delicate white flowers which shed their

petals when you simply pointed a camera at them; again we were looking

forward to August to taste the orange cloudberry fruit (Photo 14 -

Cloudberry flowers - Rubus chamaemorus at Patvinsuo). Along this stretch we

also found beautiful specimens of Bog-rosemary with their elegant pink-tinged

globular flowers (Photo 15 - Bog Rosemary (Andromeda polifolia) at Patvinsuo). That evening's wild-camp, without power for our faithful

insect-repellent Bagon-vaporiser,

meant a trying time with midges; the only consolation was the sweet scent of

wild Lilies of the Valley wafting over.

treasure, flourishing clumps of Cloudberry with

their large strawberry-like leaves and delicate white flowers which shed their

petals when you simply pointed a camera at them; again we were looking

forward to August to taste the orange cloudberry fruit (Photo 14 -

Cloudberry flowers - Rubus chamaemorus at Patvinsuo). Along this stretch we

also found beautiful specimens of Bog-rosemary with their elegant pink-tinged

globular flowers (Photo 15 - Bog Rosemary (Andromeda polifolia) at Patvinsuo). That evening's wild-camp, without power for our faithful

insect-repellent Bagon-vaporiser,

meant a trying time with midges; the only consolation was the sweet scent of

wild Lilies of the Valley wafting over. Retkeily Keskus (Trekking Centre). A board-walk led

from the well-laid out camping area down to a major set of rapids, Neitikoski,

where the wide river's foaming current, flowing at a formidable rate, spilled

over into the most horrendous set of rapids with the white water boiling up into

a swelling and churning mass. Did foolhardy souls really attempt to negotiate

such a maelstrom in canoes? The following morning we learnt that the answer was

Yes! Returning down to the water's edge to photograph the surging rapids in

bright sunlight, we witnessed brave canoeists paddling into the heart of the

rapids and skilfully riding the crest of the churning white-water; it was an

unbelievably impressive performance (Photo 16 - Canoeist on Neitikoski rapids on Lieksanjoki river). Our pursuits were however more mundane and

we set off to follow marked walking trails along the river banks past more of

the Ruunaa rapids between the lakes. From a wooden footbridge at a point where

the fast-flowing waters were channelled into a narrow gullet, we had a bird's

eye view of the rapids (Photo 17 - Rapids on Lieksanjoki river in Ruunaa Trekking Area). The path followed the river bank and negotiated marshy

areas on board-walks lined with a treasure trove of botanical gems like

Cloudberry and Cranberry flowers (Photo 18 - Cranberry flowers - Vaccinium oxycoccus) at Ruunaa) and

the first of this year's berries, Crowberries still green and unripe

(Photo 19 - Green, unripe Crowberries - Empetrium nigrum), providing us with a rival attraction to the

rapids

(Photo 20 - Board-walks crossing marshy land in Ruunaa Trekking Area).

Retkeily Keskus (Trekking Centre). A board-walk led

from the well-laid out camping area down to a major set of rapids, Neitikoski,

where the wide river's foaming current, flowing at a formidable rate, spilled

over into the most horrendous set of rapids with the white water boiling up into

a swelling and churning mass. Did foolhardy souls really attempt to negotiate

such a maelstrom in canoes? The following morning we learnt that the answer was

Yes! Returning down to the water's edge to photograph the surging rapids in

bright sunlight, we witnessed brave canoeists paddling into the heart of the

rapids and skilfully riding the crest of the churning white-water; it was an

unbelievably impressive performance (Photo 16 - Canoeist on Neitikoski rapids on Lieksanjoki river). Our pursuits were however more mundane and

we set off to follow marked walking trails along the river banks past more of

the Ruunaa rapids between the lakes. From a wooden footbridge at a point where

the fast-flowing waters were channelled into a narrow gullet, we had a bird's

eye view of the rapids (Photo 17 - Rapids on Lieksanjoki river in Ruunaa Trekking Area). The path followed the river bank and negotiated marshy

areas on board-walks lined with a treasure trove of botanical gems like

Cloudberry and Cranberry flowers (Photo 18 - Cranberry flowers - Vaccinium oxycoccus) at Ruunaa) and

the first of this year's berries, Crowberries still green and unripe

(Photo 19 - Green, unripe Crowberries - Empetrium nigrum), providing us with a rival attraction to the

rapids

(Photo 20 - Board-walks crossing marshy land in Ruunaa Trekking Area). asked what she would advise we visit in Nurmes: well there was the Old Town

with its wooden houses, and ... yes the museum, ... but that was about it

really. What about the churches? we prompted; M'mm, the Orthodox Church is only

open by arrangement, and ... well, that was about it really. Believing there

must be more to Nurmes than that, we walked through the Old Town admiring the

wooden houses along Kirkkokato (Church Street) along the top of the esker, an

attractive avenue lined with birch trees. At the far end the esker-ridge tapered down through a formally laid-out war-cemetery from 1939~44, but scattered among

the trees were 19th century metal crosses marking the graves of those who had

died of starvation after failed harvests. The TIC lady's reticence was apt: when

you had seen the esker, birch-lined Kirkkokato and the Old Town's wooden houses,

that indeed was about all of Nurmes. But Nurmes' attractiveness was its modesty;

we liked it for that, and agreed with Rough Guide's description - a little gem.

The nearby over-promoted Bomba village, a reconstruction of a Karelian log

mansion up-sticked from Suojärvi now in Russia and reassembled here appealing to

the Finns' nostalgia for lost Karelia, was a sordidly over-commercialised hotel

complex, scarcely worth a glance. And the nearby Hyvärila Camping was a noise-ridden building

site, so overwhelmed by diggers and lorries that we demanded a refund; the girl

at reception did her best to be gracious saying she hoped we should return when

the work was finished; I doubt it was our departing response.

asked what she would advise we visit in Nurmes: well there was the Old Town

with its wooden houses, and ... yes the museum, ... but that was about it

really. What about the churches? we prompted; M'mm, the Orthodox Church is only

open by arrangement, and ... well, that was about it really. Believing there

must be more to Nurmes than that, we walked through the Old Town admiring the

wooden houses along Kirkkokato (Church Street) along the top of the esker, an

attractive avenue lined with birch trees. At the far end the esker-ridge tapered down through a formally laid-out war-cemetery from 1939~44, but scattered among

the trees were 19th century metal crosses marking the graves of those who had

died of starvation after failed harvests. The TIC lady's reticence was apt: when

you had seen the esker, birch-lined Kirkkokato and the Old Town's wooden houses,

that indeed was about all of Nurmes. But Nurmes' attractiveness was its modesty;

we liked it for that, and agreed with Rough Guide's description - a little gem.

The nearby over-promoted Bomba village, a reconstruction of a Karelian log

mansion up-sticked from Suojärvi now in Russia and reassembled here appealing to

the Finns' nostalgia for lost Karelia, was a sordidly over-commercialised hotel

complex, scarcely worth a glance. And the nearby Hyvärila Camping was a noise-ridden building

site, so overwhelmed by diggers and lorries that we demanded a refund; the girl

at reception did her best to be gracious saying she hoped we should return when

the work was finished; I doubt it was our departing response. An hour's drive, passing from North Karelia into

the province of Kainuu, brought us to the outskirts of Kuhmo. Our reason for

coming to this quiet little logging town was to find the Juminkeko Centre, the

country's leading authority on everything to do with Finland's national epic,

the Kalevala. The Juminkeko Foundation is dedicated to the collection and

preservation of Karelian oral traditions of bardic folk-poetry and music which

had inspired the Kalevala's composition. Arriving at Juminkeko's modern

wooden building, we were given a knowledgeable background on Kalevala's

origins and its author Elias Lönnrot (1802~84). Lönnrot was a country doctor and

scholar from Helsinki who in the early 19th century made several expeditions

into the wilds of what is now Russian Karelia collecting and documenting the

ancient runic folk-poetry passed down by oral tradition and sung by bards often

accompanied by kantele music, the stringed zither like instrument we had heard

played at Parppeinvaara. Lönnrot assembled his collection of poetic material

into his own work which he entitled Kalevala. The first edition published

in 1835 was a conglomeration of collected material; in a second edition

published in 1849, the version of Kalevala read today as Finland's

national epic, Lönnrot rearranged his source material into a more coherent epic

tale; in his own words, he wanted to compile an epic half the size of Homer, and

it was - 22,750 lines of verse in 50 chapters. Set in an unspecified past age,

Kalevala's plot centres around the continuous wars between the mythical

land of Kalevala, often identified with Karelia, and Pohjola the land of the

North, over possession of a golden talisman called the Sampo. Many commentators

have interpreted this traditional folk-tale at the centre of Lönnrot's epic as a

symbolic representation of ancient territorial conflicts between the original

Finno-Ugric Sámi immigrants and later arriving Finns who pushed them northwards.

Lönnrot's compilation incorporates ancient creation myths, wedding songs, tales