|

CAMPING

IN ICELAND 2017 - Breiðamerkursandur, Skaftafell National Park, Fjallsárlón

and Jökulsárlón glacial lagoons,

SE coast from Höfn to Djúpivogur, East Fjords at Breiðdalvík, Stöðvarfjörður, Fáskrúðsfjörður,

Eskifjörður, Reyðarfjörður, Kárahnjúkar Dam, return to Egilsstaðir and Seyðisfjörður for Smyril

Line ferry to Denmark: CAMPING

IN ICELAND 2017 - Breiðamerkursandur, Skaftafell National Park, Fjallsárlón

and Jökulsárlón glacial lagoons,

SE coast from Höfn to Djúpivogur, East Fjords at Breiðdalvík, Stöðvarfjörður, Fáskrúðsfjörður,

Eskifjörður, Reyðarfjörður, Kárahnjúkar Dam, return to Egilsstaðir and Seyðisfjörður for Smyril

Line ferry to Denmark:

Eastwards

from Kirkjubæjarklaustur:

before leaving Kirkjubæjarklaustur, we said farewell to the German couple who

had been our neighbours in camp here, and whom we had seen up at Lakagígur

craters yesterday. They had bravely driven the F206 mountain road in their

little 4WD Lada, and we should see them again later in September since by

coincidence they also were booked on the same return Smyril Line ferry from

Seyđisfjörđur as ourselves. Having shopped for provisions at the little stores

in Kirkjubæjarklaustur village, we set off eastwards on the Ring Road (click

on Map 1 right for details of route) Eastwards

from Kirkjubæjarklaustur:

before leaving Kirkjubæjarklaustur, we said farewell to the German couple who

had been our neighbours in camp here, and whom we had seen up at Lakagígur

craters yesterday. They had bravely driven the F206 mountain road in their

little 4WD Lada, and we should see them again later in September since by

coincidence they also were booked on the same return Smyril Line ferry from

Seyđisfjörđur as ourselves. Having shopped for provisions at the little stores

in Kirkjubæjarklaustur village, we set off eastwards on the Ring Road (click

on Map 1 right for details of route)

|

Click on 5 highlighted areas of

map

for details of SE Iceland |

|

Brunasandur and Brunahraun lava field: it was a beautiful morning,

with clear blue sky and bright sunlight picking out all the details

on the

escarpment-line

of former coastal cliffs which extended along the length of the

road across the coastal plain lowlands (see above left); here the Lower Skaftá River spread out

across Brunasandur sand/gravel flood-plain through the many-channelled Landbrotsvotn estuary towards the southern coast. Farms and their lowland

pastures lined the foot of the rocky escarpment that marked the downfall from

the inland mountains. The escarpment's dark brown stratified Palagonite tuff

rock was weathered into arrays of fantastically shaped towers and outcrops, and

we paused close to where the Foss á Siða waterfalls tumbled over the brink of

the escarpment precipice to flow on past the farm at its foot (see left) (Photo 1 - Former coastal cliff-line). We began the

crossing of the Brunahraun lava field, now covered with Woolly Hair

Moss (Racomitrium lanuginosum), and set against the backdrop of the distant Vatnajökull ice-cap

and the nearer cliff-end of Kálfafell (see below right) (Photo 2 - Brunahraun lava field). The Brunahraun lava field was created by

the second series of eruptions when the NE Lakagígur fissure crater-row on the

escarpment-line

of former coastal cliffs which extended along the length of the

road across the coastal plain lowlands (see above left); here the Lower Skaftá River spread out

across Brunasandur sand/gravel flood-plain through the many-channelled Landbrotsvotn estuary towards the southern coast. Farms and their lowland

pastures lined the foot of the rocky escarpment that marked the downfall from

the inland mountains. The escarpment's dark brown stratified Palagonite tuff

rock was weathered into arrays of fantastically shaped towers and outcrops, and

we paused close to where the Foss á Siða waterfalls tumbled over the brink of

the escarpment precipice to flow on past the farm at its foot (see left) (Photo 1 - Former coastal cliff-line). We began the

crossing of the Brunahraun lava field, now covered with Woolly Hair

Moss (Racomitrium lanuginosum), and set against the backdrop of the distant Vatnajökull ice-cap

and the nearer cliff-end of Kálfafell (see below right) (Photo 2 - Brunahraun lava field). The Brunahraun lava field was created by

the second series of eruptions when the NE Lakagígur fissure crater-row opened

up in late-July 1783, pouring out vast quantities of molten lava which flooded

down the upper gorge-valley of the Hverfisfljót river, into the lowlands

destroying and burying farms and spreading out into the Brunasandur sand/gravel

flood-plain. The eruption lasted until February 1784, producing what is believed

to be one of the most voluminous flows of lava in historical times, pouring out

an estimated 14 cubic kilometres of basalt lava which covered an area of almost

600 square kilometres of territory. opened

up in late-July 1783, pouring out vast quantities of molten lava which flooded

down the upper gorge-valley of the Hverfisfljót river, into the lowlands

destroying and burying farms and spreading out into the Brunasandur sand/gravel

flood-plain. The eruption lasted until February 1784, producing what is believed

to be one of the most voluminous flows of lava in historical times, pouring out

an estimated 14 cubic kilometres of basalt lava which covered an area of almost

600 square kilometres of territory.

Nupsstaður 1650 turf huts and chapel:

the Ring Road now approached the majestic mountainous massif of

Kálfafellsheiði with its sculpted Palagonite rock towers and pillars, at the

foot of which stood the Nupsstaður Farm. This includes several preserved

turf-roofed farm buildings dating from 1650 and typical of farms of that period,

and a turf chapel, one of the few remaining such turf churches. Although

preserved by the National Museum of Iceland, the chapel at Nupsstaður is on

private property and access even to the farm driveway was regrettably barred by a distinctly

unwelcoming locked gate. The huts and church were set back far from the Ring Road and we could only peer from a distance. Nupsstaður 1650 turf huts and chapel:

the Ring Road now approached the majestic mountainous massif of

Kálfafellsheiði with its sculpted Palagonite rock towers and pillars, at the

foot of which stood the Nupsstaður Farm. This includes several preserved

turf-roofed farm buildings dating from 1650 and typical of farms of that period,

and a turf chapel, one of the few remaining such turf churches. Although

preserved by the National Museum of Iceland, the chapel at Nupsstaður is on

private property and access even to the farm driveway was regrettably barred by a distinctly

unwelcoming locked gate. The huts and church were set back far from the Ring Road and we could only peer from a distance.

The vast wastes of Skeiðarársandur sand/gravel glacial outwash flood-plain:

Route 1 now began the crossing of the mighty Skeiðarársandur sand/gravel glacial

outwash flood-plain. The Icelandic word sandur, meaning a glacial debris

outwash plain, is now used universally to describe this topographical

phenomenon. Skeiðarársandur is the world's largest sandur, a vast waste

of grey-black sands stretching 60kms west to east from Nupsstaður to Öræfi, and 40kms

from its source ice-cap to the coast, covering an area of 1,300 square kms. It

was created from all the silt, sand and gravel scraped up by the mighty

Skeiðarárjökull glacier, the largest of Vatnajökull ice-cap's glacial tongues.

This glacial and volcanic sediment and debris is then transported down to the

coastal plain both by the plain, is now used universally to describe this topographical

phenomenon. Skeiðarársandur is the world's largest sandur, a vast waste

of grey-black sands stretching 60kms west to east from Nupsstaður to Öræfi, and 40kms

from its source ice-cap to the coast, covering an area of 1,300 square kms. It

was created from all the silt, sand and gravel scraped up by the mighty

Skeiðarárjökull glacier, the largest of Vatnajökull ice-cap's glacial tongues.

This glacial and volcanic sediment and debris is then transported down to the

coastal plain both by the

Skeiðará River and a myriad of other glacial rivers,

and by glacial flash-floods (jökulhlaup) fed by the Grimsvötn and

Öræfajökull volcanic systems, and dumped across the huge desert-like flood-plain

now devoid of any vegetation (see above left). From the time of Iceland's Settlement, there were

farms in the region which over time have been swallowed up by the sandur.

The great eruption of 1362 under Öræfajökull caused jökulhlaup

flash-floods which laid waste the entire region. Skeiðarársandur was an

impassable obstacle to travellers across the region until 1974, when the final

section of the Ring Road was completed with a series of bridges constructed to

span the complex network of turbulent, ever-shifting glacial rivers flowing out

from under Skeiðarárjökull. Skeiðará River and a myriad of other glacial rivers,

and by glacial flash-floods (jökulhlaup) fed by the Grimsvötn and

Öræfajökull volcanic systems, and dumped across the huge desert-like flood-plain

now devoid of any vegetation (see above left). From the time of Iceland's Settlement, there were

farms in the region which over time have been swallowed up by the sandur.

The great eruption of 1362 under Öræfajökull caused jökulhlaup

flash-floods which laid waste the entire region. Skeiðarársandur was an

impassable obstacle to travellers across the region until 1974, when the final

section of the Ring Road was completed with a series of bridges constructed to

span the complex network of turbulent, ever-shifting glacial rivers flowing out

from under Skeiðarárjökull.

Our crossing of Skeiðarársandur:

the morning was bright and sunny as we began our crossing of Skeiðarársandur (click

here for map of route),

with perfect views across the awesome sand/gravel wastes to the distant Vatnajökull

ice-cap (see above right) (Photo 3 - Skeiðarársandur glacial outwash flood-plain). The scale and wilderness of the surrounding sandur

was fearsome enough, but the aggressively speeding tourist traffic made

this an

even more stressfully hazardous driving experience; despite our observing the

90kph speed

limit, tourist cars constantly hurtled past. Given the overwhelming

volume of tourist traffic, and the cost of maintaining this precious yet

vulnerable route across the sandur's ever-shifting terrain, the this an

even more stressfully hazardous driving experience; despite our observing the

90kph speed

limit, tourist cars constantly hurtled past. Given the overwhelming

volume of tourist traffic, and the cost of maintaining this precious yet

vulnerable route across the sandur's ever-shifting terrain, the

Icelandic Government would do well to position frequent speed cameras across this 60kms

stretch of the Ring Road. The revenue raised from speeding fines levied on

tourists or their hire car companies would constitute a viable form of tourist

taxation to contribute to the road's constant need for maintenance. The need for

maximum concentration on both the road and the speeding traffic meant that Paul

could have little appreciation of the fearsomely impressive surroundings of the

flat sand/gravel wasteland, marbled by so many melt-water channels, the distant

40kms wide glacial tongue of Skeiðarárjökull, and the eastern skyline dominated

by the Vatnajökull ice-cap. Three quarters of the way across, we were able to

pull off into a lay-by for full appreciation to the wonderful vista of the

distant ice-cap against the foreground of the sandur's desolate

wasteland (see above left) (Photo 4 - Vatnajökull backdrop). Icelandic Government would do well to position frequent speed cameras across this 60kms

stretch of the Ring Road. The revenue raised from speeding fines levied on

tourists or their hire car companies would constitute a viable form of tourist

taxation to contribute to the road's constant need for maintenance. The need for

maximum concentration on both the road and the speeding traffic meant that Paul

could have little appreciation of the fearsomely impressive surroundings of the

flat sand/gravel wasteland, marbled by so many melt-water channels, the distant

40kms wide glacial tongue of Skeiðarárjökull, and the eastern skyline dominated

by the Vatnajökull ice-cap. Three quarters of the way across, we were able to

pull off into a lay-by for full appreciation to the wonderful vista of the

distant ice-cap against the foreground of the sandur's desolate

wasteland (see above left) (Photo 4 - Vatnajökull backdrop).

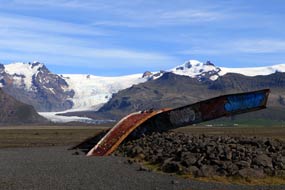

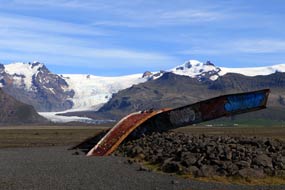

Almost across on the eastern side with the Vatnajökull

vista looming ever larger (see above right), road signs

indicated speed limits where the Ring Road was being re-routed onto a temporary

unsurfaced stretch of road by-passing a new bridge construction on a lengthy embankment (see above left) replacing earlier bridges washed away by the disastrous 1996 jökulhlaup

flash-flood. At the far side, we

reached a parking area by the site of the original Skeiðarárbru Bridge that had

once carried the Ring Road across the main channel of the Skeiðarár glacial

river. The impressive structure

left) replacing earlier bridges washed away by the disastrous 1996 jökulhlaup

flash-flood. At the far side, we

reached a parking area by the site of the original Skeiðarárbru Bridge that had

once carried the Ring Road across the main channel of the Skeiðarár glacial

river. The impressive structure

of the almost 1,000m long Skeiðarárbru Bridge had been a major engineering feat when

constructed in 1974~75, to complete the Ring Road's crossing of Skeiðarársandur.

Before that time, the unstable terrain of Skeiðarársandur was such an obstacle

to road construction that the Ring Road remained incomplete in this region.

Prior to 1974, this had meant that anyone from Höfn wishing to travel west by

road to Reykjavík had in fact to drive eastward anticlockwise all the way around the

Ring Road via Akureyri to reach the capital. But despite its scale, the bridge

was all to no avail: 20 years after its construction, in October 1996 Grimsvötn

erupted again under the Vatnajökull ice-cap. Geothermal heat from lava and ash

contained beneath the glacier melted a monumental mass of water which lifted the

ice-cap 10m before finally, after a month of anxious waiting, the inevitable

happened: the pressure of sub-glacial water outburst along a 300m wall of ice on

5 November 1996, sending 3 billion litres of water spewing across the sandur

in a 5m high tsunami, sweeping away a 7kms stretch of the Ring Road, despite the

long gravel dykes built to channel flood waters away from the highway. The Skeiðarárbru

Bridge was washed away like match sticks in less than an hour. At its height,

the jökulhlaup was surging down at of the almost 1,000m long Skeiðarárbru Bridge had been a major engineering feat when

constructed in 1974~75, to complete the Ring Road's crossing of Skeiðarársandur.

Before that time, the unstable terrain of Skeiðarársandur was such an obstacle

to road construction that the Ring Road remained incomplete in this region.

Prior to 1974, this had meant that anyone from Höfn wishing to travel west by

road to Reykjavík had in fact to drive eastward anticlockwise all the way around the

Ring Road via Akureyri to reach the capital. But despite its scale, the bridge

was all to no avail: 20 years after its construction, in October 1996 Grimsvötn

erupted again under the Vatnajökull ice-cap. Geothermal heat from lava and ash

contained beneath the glacier melted a monumental mass of water which lifted the

ice-cap 10m before finally, after a month of anxious waiting, the inevitable

happened: the pressure of sub-glacial water outburst along a 300m wall of ice on

5 November 1996, sending 3 billion litres of water spewing across the sandur

in a 5m high tsunami, sweeping away a 7kms stretch of the Ring Road, despite the

long gravel dykes built to channel flood waters away from the highway. The Skeiðarárbru

Bridge was washed away like match sticks in less than an hour. At its height,

the jökulhlaup was surging down at

50,000m3 per second, carrying with it enormous

chunks of glacial ice and boulders ripped from Skeiðarárjökull out across the

flooded sandur down to the ocean. The twisted girders of the bridge, all

that remained after the destruction, stand today as testament to the fury of the 1996 jökulhlaup

flash-flood, which demonstrated how 50,000m3 per second, carrying with it enormous

chunks of glacial ice and boulders ripped from Skeiðarárjökull out across the

flooded sandur down to the ocean. The twisted girders of the bridge, all

that remained after the destruction, stand today as testament to the fury of the 1996 jökulhlaup

flash-flood, which demonstrated how  vulnerable this stretch of the Ring Road was

(see above left)

(Photo 5 - Destroyed bridge memorial). vulnerable this stretch of the Ring Road was

(see above left)

(Photo 5 - Destroyed bridge memorial).

Hundafoss and Svartifoss waterfalls on Skaftafell:

we continued around the Ring Road, with the magnificent vista of Skaftafellsjökull looming ahead, the glacier snaking around between the crested

ridges of Skarðdartindur and Hafrafell down from the high snowfields of Vatnajökull

ice-cap (see above right). Turning off to Skaftafell National Park Visitor

Centre, we confirmed routes for our planned circular

walk this afternoon up to Svartifoss waterfalls and Skaftafell. We had imagined from the map this to be, if not a difficult climb, at least

to involve challenging route-finding in wild country. In fact, as the lad at the Visitor

Centre had advised, you simply 'follow the rubber mat road', meaning the

broad trackway rubber-reinforced for anti-erosion protection, and the hordes of tourists!

Kitting up at the parking area, we set off. The route began from the

National Park Centre, sloping uphill onto

the Skaftafellsheiði moorland and passing the Hundafoss waterfalls which dropped into

a tree-lined gorge (see right) (Photo

6 - Hundafoss waterfalls). The fellside path gained height

passing bushes of Angelica, to reveal increasing views eastwards across to the

snowfields of Öræfajökull which graced the jagged peaks of 2110m high Hvannadalsnúkur (Photo

7 - Öræfajökull topping 2110m high Hvannadalsnúkur) (see above left). Further height gain brought

a distant view of Svartifoss dropping into its basalt column-lined cove (see below

left). Scrambling down into the hollow enabled us to examine at close quarters

the magnificent vista of

Svartifoss waterfalls dropping from the fellside above

into the cove, surrounded by the most elegant basalt columnar array

(Photo

8 - Svartifoss and its basalt columns) (see below right). Basalt columns are formed as contraction

forces build up in rapidly cooling basaltic lava Svartifoss waterfalls dropping from the fellside above

into the cove, surrounded by the most elegant basalt columnar array

(Photo

8 - Svartifoss and its basalt columns) (see below right). Basalt columns are formed as contraction

forces build up in rapidly cooling basaltic lava

flow; shrinkage contraction causes the new igneous rock to develop fracture networks resulting in formation of the

6-sided columns. The columns always form at right angles to the cooling surface

where heat loss is greatest (see diagram below right); this means that vertical

columns are created when a basaltic lava intrusion flows into horizontal cracks in the

bed-rock (sills), and horizontal columns when the lava intrusion flows into vertical cracks

(dykes). Where the cooling surface is irregular, the columns radiate in many

directions. Hexagonal columns are the most common since fracture patterns with

120º corners are the most efficient for stress resistance as in dried up muddy

ponds, or freeze-thaw patterns in the ground. Hence 6-sided patterns are seen

widely in nature as the most efficient close-packing use of space (eg honeycombs).

Whatever the technical geological explanation of basalt column formation, there

was no denying the beauty in their visual aesthetics and the elegance of the

columns' symmetry, seen to best effect here at Svartifoss.

flow; shrinkage contraction causes the new igneous rock to develop fracture networks resulting in formation of the

6-sided columns. The columns always form at right angles to the cooling surface

where heat loss is greatest (see diagram below right); this means that vertical

columns are created when a basaltic lava intrusion flows into horizontal cracks in the

bed-rock (sills), and horizontal columns when the lava intrusion flows into vertical cracks

(dykes). Where the cooling surface is irregular, the columns radiate in many

directions. Hexagonal columns are the most common since fracture patterns with

120º corners are the most efficient for stress resistance as in dried up muddy

ponds, or freeze-thaw patterns in the ground. Hence 6-sided patterns are seen

widely in nature as the most efficient close-packing use of space (eg honeycombs).

Whatever the technical geological explanation of basalt column formation, there

was no denying the beauty in their visual aesthetics and the elegance of the

columns' symmetry, seen to best effect here at Svartifoss.

Skaftafell:

leaving the tourists to their silly antics around the falls, we crossed the

stream descending from Svartifoss to begin the climb up onto the open heath-land

of Skaftafellsheiði. As we crossed the foot-bridge, a little Icelandic Wren

hopped around on Skaftafell:

leaving the tourists to their silly antics around the falls, we crossed the

stream descending from Svartifoss to begin the climb up onto the open heath-land

of Skaftafellsheiði. As we crossed the foot-bridge, a little Icelandic Wren

hopped around on the boulders beneath our feet. Emerging

onto the open moorland

brought us out onto

a peaceful fell-side carpeted with low birch and willow scrub and a ground cover of

Crowberry and Bearberry with its ripening red berries (see left) (Photo

9 - Bearberry). Our photographic attention was divided between the

ground cover berries and the magnificent panorama N towards the Vatnajökull

ice-cap, and NW over to the distant jagged, crested peak and ridges of Hvannadalsnúkur,

Iceland's highest mountain at 2110m, and the nearer shapely ridge of Hafrafell

which now divides Skaftafellsjökull from its neighbouring outlet glacier of

Svinafellsjökull (see below left) (Photo

10 - Hvannadalsnúkur and Hafrafell).

the boulders beneath our feet. Emerging

onto the open moorland

brought us out onto

a peaceful fell-side carpeted with low birch and willow scrub and a ground cover of

Crowberry and Bearberry with its ripening red berries (see left) (Photo

9 - Bearberry). Our photographic attention was divided between the

ground cover berries and the magnificent panorama N towards the Vatnajökull

ice-cap, and NW over to the distant jagged, crested peak and ridges of Hvannadalsnúkur,

Iceland's highest mountain at 2110m, and the nearer shapely ridge of Hafrafell

which now divides Skaftafellsjökull from its neighbouring outlet glacier of

Svinafellsjökull (see below left) (Photo

10 - Hvannadalsnúkur and Hafrafell).

Further height gain up the open heath-land

slope brought us to the high point of Sjónarsker; from here a sweeping

panorama opened up westwards to where the broad front of Skeiðarárjökull outlet

glacier crept down towards the vast open outwash flood-plain of Skeiðarársandur

which stretched away towards the coast on the misty southern horizon. Even

further

westwards,

we could just make out the moss-covered Brunahraun lava field catching the

afternoon sun. Beginning the descent, we followed way-marked tracks, still with

much height to loose. The path descended through high birch scrub alongside the Bæjargil stream dropping down the deep, rocky gorge below Hundafoss. At the foot

of this, a path crossed the beck on a wooden footbridge, leading back through the Skaftafell campsite to the Visitor Centre. westwards,

we could just make out the moss-covered Brunahraun lava field catching the

afternoon sun. Beginning the descent, we followed way-marked tracks, still with

much height to loose. The path descended through high birch scrub alongside the Bæjargil stream dropping down the deep, rocky gorge below Hundafoss. At the foot

of this, a path crossed the beck on a wooden footbridge, leading back through the Skaftafell campsite to the Visitor Centre.

Svinafellsjökull glacier snout and lagoon: back out to the Ring

Road, we crossed the glacial River Skaftafellsá which pours down from the Skaftafellsjökull

outlet glacier, and turned off onto a rough and pot-holed gravel track-way which

led across the grey terminal moraine (click

here for map of route). The roadway rounded

moraine hillocks to end at a small parking area beneath the prow-end tip of the

Hafrafell ridge, and from here a path led over

the rocks to overlook Skaftafellsjökull's glacial lagoon. Misty cloud now

hovered around the surrounding mountains, giving the enclosed snout of the

glacier a gloomy and eerily silent atmosphere (see right). The grey, sediment-rich icy water

was backed by the blue-grey glacial snout, with the occasional splash as chunks

of ice fell from the glacier's end walls into the lagoon. We edged a way

uncertainly upwards over the rocky side-shelf, to gain a clearer view onto the

sediment-stained lower ice-field which was fractured by crevasses, the more open

ice-cliffs glowing a vivid Svinafellsjökull glacier snout and lagoon: back out to the Ring

Road, we crossed the glacial River Skaftafellsá which pours down from the Skaftafellsjökull

outlet glacier, and turned off onto a rough and pot-holed gravel track-way which

led across the grey terminal moraine (click

here for map of route). The roadway rounded

moraine hillocks to end at a small parking area beneath the prow-end tip of the

Hafrafell ridge, and from here a path led over

the rocks to overlook Skaftafellsjökull's glacial lagoon. Misty cloud now

hovered around the surrounding mountains, giving the enclosed snout of the

glacier a gloomy and eerily silent atmosphere (see right). The grey, sediment-rich icy water

was backed by the blue-grey glacial snout, with the occasional splash as chunks

of ice fell from the glacier's end walls into the lagoon. We edged a way

uncertainly upwards over the rocky side-shelf, to gain a clearer view onto the

sediment-stained lower ice-field which was fractured by crevasses, the more open

ice-cliffs glowing a vivid

aquamarine blue. The only sound to disturb the eerie

silence was the cracking and groaning of the ice, and the occasional splash as

chunks of ice broke off into the lagoon. In the murky northern distance,

the upper end of the outlet glacier's lower ice-field, enclosed by the craggy

side of Hafrafell, rose seemingly vertical onto the main ice-cap of Vatnajökull (Photo

11 - Svinafellsjökull outlet-glacier) (see left and below right). This was a truly fearful,

heart-stopping vista to savour in undisturbed silence. Edging our way back over

the rock-shelf above the sheer drop into the lagoon's icy-cold, grey waters, we

passed a lone young aquamarine blue. The only sound to disturb the eerie

silence was the cracking and groaning of the ice, and the occasional splash as

chunks of ice broke off into the lagoon. In the murky northern distance,

the upper end of the outlet glacier's lower ice-field, enclosed by the craggy

side of Hafrafell, rose seemingly vertical onto the main ice-cap of Vatnajökull (Photo

11 - Svinafellsjökull outlet-glacier) (see left and below right). This was a truly fearful,

heart-stopping vista to savour in undisturbed silence. Edging our way back over

the rock-shelf above the sheer drop into the lagoon's icy-cold, grey waters, we

passed a lone young German visitor who, with quaintly charming, old fashioned

courtesy offered Sheila an assisting hand, and took our photo against

this astonishing glacial backdrop (Photo

12 - Svinafellsjökull glacier snout) (see below left).

German visitor who, with quaintly charming, old fashioned

courtesy offered Sheila an assisting hand, and took our photo against

this astonishing glacial backdrop (Photo

12 - Svinafellsjökull glacier snout) (see below left).

Skaftafell National Park campsite:

we bumped our way back to the Ring Road and drove eastwards in now murky light

to investigate what appeared to be the preferred campsite option at Svinafell Farm. Just off the main road under the brooding shadow of Hvannadalsnúkur

and Öræfajökull way above hidden in the misty cloud, there had been a farmstead

here at Svinafell going right back to Njál's Saga times. where settlers had

attempted to eke out a living. The little campsite was well laid out with straightforward facilities, but

unfortunately no power supplies. Although more attractive and better value than

the National Park campsite at Skaftafell, to face days in camp in this chill,

wet weather here at Svinafell without power was not an option. We therefore with

regret returned around to Skaftafell, reaching the reception at 7-00pm. As with

the equivalent Jökulsárgljúfur National

Park campsite at Asbyrgi in the north, the National Park Authority exploited its

almost monopolistic position to charge off-the-planet prices for camping here

at Skaftafell: 1,600kr/person (no seniors' discount), 900kr for power, plus

500kr for showers, making a potential total of 5,100kr (£40). The lad at

reception responded to our protestations in typical Jobsworth manner with I

just work here, I don't make the rules. We had our own means however of

dealing with such a monopolistic rip-off!

The little campsite was well laid out with straightforward facilities, but

unfortunately no power supplies. Although more attractive and better value than

the National Park campsite at Skaftafell, to face days in camp in this chill,

wet weather here at Svinafell without power was not an option. We therefore with

regret returned around to Skaftafell, reaching the reception at 7-00pm. As with

the equivalent Jökulsárgljúfur National

Park campsite at Asbyrgi in the north, the National Park Authority exploited its

almost monopolistic position to charge off-the-planet prices for camping here

at Skaftafell: 1,600kr/person (no seniors' discount), 900kr for power, plus

500kr for showers, making a potential total of 5,100kr (£40). The lad at

reception responded to our protestations in typical Jobsworth manner with I

just work here, I don't make the rules. We had our own means however of

dealing with such a monopolistic rip-off!

Fearing we should be hemmed in by camping-cars,

we found a pitch in the corner of a formally laid out enclosure, with clear views

over towards the two outlet glaciers of Skaftafellsjökull and Svinafellsjökull

(see right); the intervening ridge-line of Hafrafell

was topped by the serrated peaks of Hvannadalsnúkur

and beyond, the upper ice-fields of Öræfajökull. With the trip's timescale ticking

towards its conclusion and Iceland's autumnal weather now closing in, we lit the

final barbecue for supper, and settled in on a very dark evening. Fearing we should be hemmed in by camping-cars,

we found a pitch in the corner of a formally laid out enclosure, with clear views

over towards the two outlet glaciers of Skaftafellsjökull and Svinafellsjökull

(see right); the intervening ridge-line of Hafrafell

was topped by the serrated peaks of Hvannadalsnúkur

and beyond, the upper ice-fields of Öræfajökull. With the trip's timescale ticking

towards its conclusion and Iceland's autumnal weather now closing in, we lit the

final barbecue for supper, and settled in on a very dark evening.

A wet day in camp at Skaftafell:

today was the first of several forecast wet days, to be spent in camp here at

Skaftafell, catching up after an intensive period of travel. If only the

National Park had provided facilities at its Skaftafell campsite of a

commensurate standard with its grossly inflated prices, but of course it didn't!

Given the size of the campsite, facilities were basic and unduly limited: just 2

WCs, with a queue of wet and bedraggled campers queuing outside in the rain to

use them, 2 showers largely unused given the

excessive additional cost, and one

wash-up sink with lukewarm water. There were absolutely no cooking facilities or

covered area for shelter for the large number of tent campers. Given this, and

the extortionate prices charged by the fat-cat National Park bureaucrats from

Reykjavík who run the campsite, Skaftafell

was an absolute disgrace deserving the negative rating we gave it. But of course

as with any monopoly, the consumer has no choice but to pay up, or like us play

them at their own game! excessive additional cost, and one

wash-up sink with lukewarm water. There were absolutely no cooking facilities or

covered area for shelter for the large number of tent campers. Given this, and

the extortionate prices charged by the fat-cat National Park bureaucrats from

Reykjavík who run the campsite, Skaftafell

was an absolute disgrace deserving the negative rating we gave it. But of course

as with any monopoly, the consumer has no choice but to pay up, or like us play

them at their own game!

Skaftafellsjökull terminal moraine and glacial snout:

with a fine day forecast before the next lot of rain rolled in tomorrow, we

planned today to walk out across the glacial outwash plain and terminal moraine

fields to the lagoon and snout of the larger Skaftafellsjökull. The tongues of Vatnajökull's

two southern outlet glaciers, Skaftafellsjökull and Svinafellsjökull, once

merged along this valley below the leading prow-edge of Hafrafell's ridge as is

shown on a Danish 1904 geological survey map

(Click here for 1904 map of merged glaciers). But since that

time, the two glaciers have retreated substantially during the 20th century,

gradually exposing the land along the lower valley. Contrast the 1904 map with

the equivalent 2017 map which shows the scale of the two now separated glaciers'

retreat (Click here for 2017 map of glaciers' retreat).

This 2017 map shows both the route of our earlier visit to the terminal snout of Svinafellsjökull

along the rough track, and

today's walk from the National Park Visitor Centre

(Skaftafellsstofa) along Skaftafellsjökull's now exposed outwash plain to its

glacial snout and terminal lagoon. Vegetation has gradually

colonised the outwash plain and moraine left behind by the retreating ice with a

succession of plant species. At the 1904 level of the retreating ice at the open

outer end of the valley, the vegetation was now lush with birch and willow scrub

and Crowberry ground-cover and Bearberry with its bright red berries. today's walk from the National Park Visitor Centre

(Skaftafellsstofa) along Skaftafellsjökull's now exposed outwash plain to its

glacial snout and terminal lagoon. Vegetation has gradually

colonised the outwash plain and moraine left behind by the retreating ice with a

succession of plant species. At the 1904 level of the retreating ice at the open

outer end of the valley, the vegetation was now lush with birch and willow scrub

and Crowberry ground-cover and Bearberry with its bright red berries. As we

moved up the valley however, the vegetation became progressively less diverse

and more stunted, with finally the most recently exposed moraine close to the

terminal lagoon being bare grey gravel deposit. As we

moved up the valley however, the vegetation became progressively less diverse

and more stunted, with finally the most recently exposed moraine close to the

terminal lagoon being bare grey gravel deposit.

We walked along the moraine valley at a

leisurely pace enjoying the wealth of flora, and at the inner end rose up onto

the bare ridge of moraine gravel. There before us was the most recent vast area

of bare, grey gravel and sand, exposed from the glacier's terminal from 1980

onwards, the flatness of this 'new land' indicating that in the last 35 years,

the ice had melted and Skaftafellsjökull retreated at a faster rate than

previously. Earlier in the comparative shelter of the moraine valley, it had

felt quite warm; but now on this higher, more exposed vantage point, the cold

air blowing down from the higher ice-field suddenly hit us. We quickly donned

jackets, muffs and hats in the now very chill breeze. But the view! Utterly

awe-inspiring, looking across the broad glacial lagoon where small, recently

detached icebergs from the

glacier's leading edge floated in the sediment-laden,

grey waters (see above left and right) (Photo

13 - Skaftafellsjökull glacial snout). And rising up from the lagoon, the nearest corner of the glacial

ice snout was filthy grey with sediment. Further up, the crevasse-scarred,

cleaner ice gleamed a bright aquamarine blue, while higher still, the upper

reached of Skaftafellsjökull rose steeply in the distance towards the

ice-field of Vatnajökull. We stood admiring this glacier's leading edge floated in the sediment-laden,

grey waters (see above left and right) (Photo

13 - Skaftafellsjökull glacial snout). And rising up from the lagoon, the nearest corner of the glacial

ice snout was filthy grey with sediment. Further up, the crevasse-scarred,

cleaner ice gleamed a bright aquamarine blue, while higher still, the upper

reached of Skaftafellsjökull rose steeply in the distance towards the

ice-field of Vatnajökull. We stood admiring this fairy-tale ice-scape and

speculated on the causes of the snout end being so filthy: sediment scoured out

from the bed-rock over aeons by the glacier's downward movement, ash fallout

from nearby volcanic eruptions, or wind-blown fine particulate material from the

moraine field all being concentrated at the glacier's melting leading-edge.

Alongside the high mounds and moraine ridge where we stood, two large

kettle-holes showed where huge blocks of ice, broken off from the glacier's

snout at an earlier stage and left behind by the retreating glacier, became

buried in the till (glacier-borne sediment) or fluvio-glacial deposits (sediment

carried by glacial rivers); the ice blocks eventually melted to leave large

depressions in the outwash plain which filled with water, forming lakes (see above

left). fairy-tale ice-scape and

speculated on the causes of the snout end being so filthy: sediment scoured out

from the bed-rock over aeons by the glacier's downward movement, ash fallout

from nearby volcanic eruptions, or wind-blown fine particulate material from the

moraine field all being concentrated at the glacier's melting leading-edge.

Alongside the high mounds and moraine ridge where we stood, two large

kettle-holes showed where huge blocks of ice, broken off from the glacier's

snout at an earlier stage and left behind by the retreating glacier, became

buried in the till (glacier-borne sediment) or fluvio-glacial deposits (sediment

carried by glacial rivers); the ice blocks eventually melted to leave large

depressions in the outwash plain which filled with water, forming lakes (see above

left).

Around the

top of the moraine ridge, an area of

moss-covered boulders provided another unique spot for eating our lunch

sandwiches, as we sat looking up across the glacier's tongue dropping down from

the Vatnajökull snow fields (Photo

14 - Lunch on lateral moraine) (see above right). From here we descended onto the flat

wash-out moraine field across to the edge of the terminal lagoon. Melt-water

surged at a terrifying rate from under the leading edge of the ice (see above

left), and further

round sunlight picked out the floating icebergs giving them an aquamarine tinge Around the

top of the moraine ridge, an area of

moss-covered boulders provided another unique spot for eating our lunch

sandwiches, as we sat looking up across the glacier's tongue dropping down from

the Vatnajökull snow fields (Photo

14 - Lunch on lateral moraine) (see above right). From here we descended onto the flat

wash-out moraine field across to the edge of the terminal lagoon. Melt-water

surged at a terrifying rate from under the leading edge of the ice (see above

left), and further

round sunlight picked out the floating icebergs giving them an aquamarine tinge (see above right) (Photo

15 - Glacial icebergs).

Back up onto the high moraine ridge, we followed this around to a point which

gave a fuller view across the ice-filled corner of the lagoon up onto the full

sweep of the glacier's upper ice-field

(Photo

16 - Skaftafellsjökull's full sweep) (see left and right). From here, escaping all the noise of the

tourists now flocking along the valley in increasing numbers, we followed an

alternative route back across the moraine-field; the further we moved away from Skaftafellsjökull's

current leading-edge, the more lush the vegetation and flora became (see below left), and warmer the air noticeably

felt.

(see above right) (Photo

15 - Glacial icebergs).

Back up onto the high moraine ridge, we followed this around to a point which

gave a fuller view across the ice-filled corner of the lagoon up onto the full

sweep of the glacier's upper ice-field

(Photo

16 - Skaftafellsjökull's full sweep) (see left and right). From here, escaping all the noise of the

tourists now flocking along the valley in increasing numbers, we followed an

alternative route back across the moraine-field; the further we moved away from Skaftafellsjökull's

current leading-edge, the more lush the vegetation and flora became (see below left), and warmer the air noticeably

felt.

Another wet day at Skaftafell Camping:

back at the Skaftafell Visitor Centre, we had hoped to see the video

showing the devastation caused by the 1996 jökulhlaup

flash-flood. But, a sign of the times, this was no longer available, replaced by

a tourist-oriented, dumbed-down superficial film on the

National Park;

disappointed we returned to the campsite. Today had been a thoroughly educative

day out at the glacier's edge, enabling good opportunity for glacial

photography. As dusk approached and gloomy darkness fell, misty cloud gathered

and drizzly rain began as a prelude to tomorrow's forecast louring rain; and the

tourist hire cars and camping-cars swarmed in with much slamming of car doors

until late into the evening. The following day was only fit for National Park;

disappointed we returned to the campsite. Today had been a thoroughly educative

day out at the glacier's edge, enabling good opportunity for glacial

photography. As dusk approached and gloomy darkness fell, misty cloud gathered

and drizzly rain began as a prelude to tomorrow's forecast louring rain; and the

tourist hire cars and camping-cars swarmed in with much slamming of car doors

until late into the evening. The following day was only fit for another day in

camp, and the rain continued well into the morning; we still had much catching

up to do and put the wet day to good use. The rain eased early afternoon and sky

cleared a little, enabling us at least to get washing up done without a soaking,

but early evening the clouds gathered again over the surrounding mountains, and

rain began again driven by the south-easterly gale. The pouring rain continued

all evening on a very dark and wretchedly wet night. another day in

camp, and the rain continued well into the morning; we still had much catching

up to do and put the wet day to good use. The rain eased early afternoon and sky

cleared a little, enabling us at least to get washing up done without a soaking,

but early evening the clouds gathered again over the surrounding mountains, and

rain began again driven by the south-easterly gale. The pouring rain continued

all evening on a very dark and wretchedly wet night.

The Öræfi wasteland and turf-roofed church at Hof:

it rained solidly all night, but by the time we woke the following morning the sky

was beginning to clear, and as we sat eating breakfast, the sun broke through

bringing a restorative warmth. It was for the moment a beautiful morning after

all the rain. Leaving Skaftafell (click

here for map of route), Route 1  Ring Rind crossed the main,

fast-flowing and sediment-laden Skaftafellsá glacial river pouring out from Skaftafellsjökull and Svinafellsjökull (see right)

(Photo

17 - Skaftafellsá glacial river).

We headed south under the slopes of the mighty peak of Hvannadalsnúkur and across the partly vegetated wasteland of Öræfi

(see left)

(Photo

18 - Hvannadalsnúkur, Iceland's highest peak). The peak's ridges, protruding

from the equally formidable Öræfajökull (Photo

19 - Öræfajökull glacier) (see below right), form the NW edge of an immense 5kms

wide caldera, the biggest Ring Rind crossed the main,

fast-flowing and sediment-laden Skaftafellsá glacial river pouring out from Skaftafellsjökull and Svinafellsjökull (see right)

(Photo

17 - Skaftafellsá glacial river).

We headed south under the slopes of the mighty peak of Hvannadalsnúkur and across the partly vegetated wasteland of Öræfi

(see left)

(Photo

18 - Hvannadalsnúkur, Iceland's highest peak). The peak's ridges, protruding

from the equally formidable Öræfajökull (Photo

19 - Öræfajökull glacier) (see below right), form the NW edge of an immense 5kms

wide caldera, the biggest active volcano in Europe after Etna. The

glacier-covered Öræfajökull volcano erupted explosively in 1362 ejecting huge

amounts of tephra, and obliterated the entire region with floods and tephra-fall

and causing its total abandonment; the name Öræfi in Icelandic has come to

mean Desolation. This had always been an isolated region, cut off by the

impassable sandur to east and west, by the mountainous interior and

ice-caps to the north, and by a harbourless wild coastline to the south.

active volcano in Europe after Etna. The

glacier-covered Öræfajökull volcano erupted explosively in 1362 ejecting huge

amounts of tephra, and obliterated the entire region with floods and tephra-fall

and causing its total abandonment; the name Öræfi in Icelandic has come to

mean Desolation. This had always been an isolated region, cut off by the

impassable sandur to east and west, by the mountainous interior and

ice-caps to the north, and by a harbourless wild coastline to the south.

Before rounding the southern tip of the Öræfi

headland, the road reached the tiny farming hamlet of Hof which nestles into the

protective mountainous cliffs; on a sunny morning with the clear sky a deep

blue, the farmstead looked a tiny green oasis in this

inhospitable

wasteland, surrounded by its pastureland. We turned off Route 1 to the

settlement to visit the little turf-roofed Hof church. Built on the foundations

of an earlier 14th century church, the current church at Hof dates from 1884.

The turf-covered roof slopes down to the thick stone side walls, and the 2

gable-ends are built of timber. The church and graveyard stood in a grove of birch

and rowan and were backed by the Öræfajökull mountains, lit by the lovely morning sunshine

(Photo

20 - Turf-roofed Hof church) (see left). Having taken our photos, we

returned to the Ring Road to continue our journey. inhospitable

wasteland, surrounded by its pastureland. We turned off Route 1 to the

settlement to visit the little turf-roofed Hof church. Built on the foundations

of an earlier 14th century church, the current church at Hof dates from 1884.

The turf-covered roof slopes down to the thick stone side walls, and the 2

gable-ends are built of timber. The church and graveyard stood in a grove of birch

and rowan and were backed by the Öræfajökull mountains, lit by the lovely morning sunshine

(Photo

20 - Turf-roofed Hof church) (see left). Having taken our photos, we

returned to the Ring Road to continue our journey.

Eastern Skeiðarársandur, Ingólfshöfði and Kviárjökull:

Rounding the southern tip of Öræfi, and looking out across the easternmost

wastes of Skeiðarársandur, the skyline was dominated by the massive headland of Ingólfshöfði,

the cape terminating the sandbar which extends along the outer width of the

Leirur outwash-plain (see right). The headland is named after Iceland's legendary first

settler, Ingólfur Arnasson, who is said to have made his original landfall here

in 874 AD before sailing on to found his farm at what became Reykjavík. The

isolated headland is now a nature reserve for nesting sea birds, mainly Puffins

and Great Skuas, and the local

farm operates tractor tours across the

treacherous sandur and marshes. We paused at the turning from the Ring

Road to gaze across the Skeiðarársandur outwash-plain at the silhouetted

headland. Continuing on Route 1 (click

here for map of route), rounding the sweep of dramatic glacier-topped

mountains, with the weather now heavily overcast, we reached the turning for Kviárjökull,

just before the bridge across the Kvíá river pouring down from the glacier. 300m along a bumpy dirt road, we paused at

a parking area alongside the glacial river to eat our lunch sandwiches and to

wait for a squally shower to pass. The sky had darkened and a rainbow spanned

the misty fell-side and savage farm operates tractor tours across the

treacherous sandur and marshes. We paused at the turning from the Ring

Road to gaze across the Skeiðarársandur outwash-plain at the silhouetted

headland. Continuing on Route 1 (click

here for map of route), rounding the sweep of dramatic glacier-topped

mountains, with the weather now heavily overcast, we reached the turning for Kviárjökull,

just before the bridge across the Kvíá river pouring down from the glacier. 300m along a bumpy dirt road, we paused at

a parking area alongside the glacial river to eat our lunch sandwiches and to

wait for a squally shower to pass. The sky had darkened and a rainbow spanned

the misty fell-side and savage mountainous backdrop

(see left) (Photo

21 - Rainbow over Kvíá glacial river). When the storm passed, we walked

up over the hillocks of the lower valley for the magnificent vista of Kviárjökull,

one of Öræfajökull's principal outlet glaciers,

snaking its way elegantly down between the enclosing peaks, (see right) (Photo

22 - Kviárjökull, outlet glacier of Öræfajökull). mountainous backdrop

(see left) (Photo

21 - Rainbow over Kvíá glacial river). When the storm passed, we walked

up over the hillocks of the lower valley for the magnificent vista of Kviárjökull,

one of Öræfajökull's principal outlet glaciers,

snaking its way elegantly down between the enclosing peaks, (see right) (Photo

22 - Kviárjökull, outlet glacier of Öræfajökull).

Fjallsjökull glacier and Fjallsárlón glacial

lagoon:

a short distance along this desolate coastline, a turning led to the glacial

lagoons of Fjallsárlón and Breiðárlón (click

here for map of route). The first of these lagoons lies at the

foot of Fjallsjökull glacier and the smaller adjacent Hrútárjökull both of which

glaciers, along with Kviárjökull, are outlet glaciers of Öræfajökull. The

neighbouring

and broader fronted Breiðamerkurjökull drains down into Breiðárlón

and Jökulsárlón lagoons. Both parent glaciers Öræfajökull and Breiðamerkurjökull,

along with many other glaciers, themselves form outlet-glaciers of the grandfather of

them all, the mighty Vatnajökull ice-cap; Iceland's largest glacier, Vatnajökull covers an area of over 8,000 square kms (8% of the

country), 1,000m deep at its thickest point, and also Europe's greatest ice mass. and broader fronted Breiðamerkurjökull drains down into Breiðárlón

and Jökulsárlón lagoons. Both parent glaciers Öræfajökull and Breiðamerkurjökull,

along with many other glaciers, themselves form outlet-glaciers of the grandfather of

them all, the mighty Vatnajökull ice-cap; Iceland's largest glacier, Vatnajökull covers an area of over 8,000 square kms (8% of the

country), 1,000m deep at its thickest point, and also Europe's greatest ice mass.

A rough trackway forked right to Breiðárlón,

but we took the left fork to a parking area below Fjallsárlón. Climbing up onto

the terminal moraine gravelly hillock, the magnificent vista opened up of the

twin glaciers of Fjallsjökull and Hrútárjökull (Photo

23 - Hrútárjökull and Fjallsjökull) (see left); these both snaked down the hillside

opposite between enclosing ridges, from the distant higher snowfields of Öræfajökull, down to the

fractured and crevasse-ridden leading-edge of the grey-streaked and aquamarine-blue

ice tongue above the huge glacial lagoon (see right) (Photo

24 - Fjallsárlón glacial lagoon). The lagoon itself was filled with

ice-bergs of every size and shape, which had calved from the glacier ice's

leading edge (Photo

25 - Icebergs floating on Fjallsárlón) (see below

left), and now floated in graceful silence

around the lagoon (Photo

26- Floating glacial icebergs). We clambered down the steep, gravelly slope to

the water's edge to gaze out across the glacial lagoon and the floating armada

of icebergs (see below right) (Photo

27- Fjallsjökull and distant Öræfajökull), many melted into fantastic

shapes (see below left); one resembled a swan with curving neck, another a

narrow stemmed mushroom. Every so often, the silence was broken by

a distant rumble and crash just like thunder, as further huge chunks of ice broke

from the markedly turquoise-blue leading-edge left), and now floated in graceful silence

around the lagoon (Photo

26- Floating glacial icebergs). We clambered down the steep, gravelly slope to

the water's edge to gaze out across the glacial lagoon and the floating armada

of icebergs (see below right) (Photo

27- Fjallsjökull and distant Öræfajökull), many melted into fantastic

shapes (see below left); one resembled a swan with curving neck, another a

narrow stemmed mushroom. Every so often, the silence was broken by

a distant rumble and crash just like thunder, as further huge chunks of ice broke

from the markedly turquoise-blue leading-edge of the glacier's ice (Photo

28 - Fragmented glacier leading-edge), sending mini-tsunamis flooding across the sediment-grey water. A chilling cold wind blew across the

lagoon from

the glacier as we stood to take our photos (Photo

29 - Chill glacial wind). Chunks of the crystal clear ice floated

onto the shore-line, and picking up these pieces of glacial ice (Photo

30 - Glacial ice), it was intriguing to wonder just how old they were or

from which part of the glacier they had broken. Considering the number of

tourist cars at the parking area, we were fortunate to enjoy a remarkably

peaceful and undisturbed hour by the shore-side, looking out across the lagoon (Photo

31- Fjallsjökull glacial slopes) to the floating icebergs, and the

glacial slopes and snow fields beyond. of the glacier's ice (Photo

28 - Fragmented glacier leading-edge), sending mini-tsunamis flooding across the sediment-grey water. A chilling cold wind blew across the

lagoon from

the glacier as we stood to take our photos (Photo

29 - Chill glacial wind). Chunks of the crystal clear ice floated

onto the shore-line, and picking up these pieces of glacial ice (Photo

30 - Glacial ice), it was intriguing to wonder just how old they were or

from which part of the glacier they had broken. Considering the number of

tourist cars at the parking area, we were fortunate to enjoy a remarkably

peaceful and undisturbed hour by the shore-side, looking out across the lagoon (Photo

31- Fjallsjökull glacial slopes) to the floating icebergs, and the

glacial slopes and snow fields beyond.

Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon and

Jökulsá River:

10kms east along the Ring Road brought us to the bridge over the Jökulsá River

which drained down seaward from the Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon (click

here for map of route). The parking area

on the far side was over-spilling with tourist cars and tour-buses; we therefore

turned off into the less crowded parking area on the western side of the bridge.

Again we followed a pathway around the gravelly moraine slopes overlooking the Jökulsárlón Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon and

Jökulsá River:

10kms east along the Ring Road brought us to the bridge over the Jökulsá River

which drained down seaward from the Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon (click

here for map of route). The parking area

on the far side was over-spilling with tourist cars and tour-buses; we therefore

turned off into the less crowded parking area on the western side of the bridge.

Again we followed a pathway around the gravelly moraine slopes overlooking the Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon

(see below right) (Photo 32 - Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon). Until the 1940s, all these glaciers were merged into

one with its leading edge stretching right down to the coast where icebergs

calved directly into the North Atlantic Ocean. As the glaciers receded, they formed

their own individual identities over the last 70 years, each with their own glacial

lagoon where the ice had gouged out depressions in the terminal moraine below

the glacial tongue; these filled with sediment-laden melt-water and giant

chunks of ice breaking from the glaciers' ends. The Jökulsá River, just 50m long,

now drains down from Jökulsárlón to the sea, and smaller ice-boulders swirled

around in the surging current (Photo

33 - Swirling ice-boulders), performing a merry-go-round dance where the

down-flow of glacial melt-water met the opposing incoming tidal wash from the

sea just 50m away. Across the Jökulsárlón lagoon, icebergs and

ice-boulders of every size and shape, some massive, others just small glacial lagoon

(see below right) (Photo 32 - Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon). Until the 1940s, all these glaciers were merged into

one with its leading edge stretching right down to the coast where icebergs

calved directly into the North Atlantic Ocean. As the glaciers receded, they formed

their own individual identities over the last 70 years, each with their own glacial

lagoon where the ice had gouged out depressions in the terminal moraine below

the glacial tongue; these filled with sediment-laden melt-water and giant

chunks of ice breaking from the glaciers' ends. The Jökulsá River, just 50m long,

now drains down from Jökulsárlón to the sea, and smaller ice-boulders swirled

around in the surging current (Photo

33 - Swirling ice-boulders), performing a merry-go-round dance where the

down-flow of glacial melt-water met the opposing incoming tidal wash from the

sea just 50m away. Across the Jökulsárlón lagoon, icebergs and

ice-boulders of every size and shape, some massive, others just small

chunks,

floated around the lagoon water; some were stationary, others glided silently

around. Some smaller pieces were sparklingly crystal clear, other larger pieces

were streaked with volcanic ash fallout (Photo

34 - Volcanic ash-streaked icebergs), while others were vivid

aquamarine-blue. This blue colour of the ice indicated a smooth surface with few

trapped air bubbles, due either to having been subjected to severe pressure or

having partially melted under water. Again many of the icebergs were

melting into chunks,

floated around the lagoon water; some were stationary, others glided silently

around. Some smaller pieces were sparklingly crystal clear, other larger pieces

were streaked with volcanic ash fallout (Photo

34 - Volcanic ash-streaked icebergs), while others were vivid

aquamarine-blue. This blue colour of the ice indicated a smooth surface with few

trapped air bubbles, due either to having been subjected to severe pressure or

having partially melted under water. Again many of the icebergs were

melting into weird shapes (Photo

35 - Weirdly shaped glacial icebergs) (see left), and as the current

picked up individual bergs, they moved rapidly towards the river's exit channel;

most however remained

stationary in majestic silence (see below left). Seals could be seen swimming around the lagoon

among the floating chunks of ice, their snouts just protruding from the water,

and Eider ducks bobbed around closer to the shore-line (see right). All of this was

happening against the backdrop of the great sweep of the Breiðamerkurjökull

glacier which loomed down from the higher ice-fields (Photo

36 - Breiðamerkurjökull glacier).

We spent another hour walking along the moraine slopes above the lagoon taking our photos. Remarkably,

despite the hordes of tourists who flock here in swarms, we managed to find

peace and seclusion in this western area of the Jökulsárlón lagoon to enjoy this

magnificent spectacle without disturbance or intrusion.

weird shapes (Photo

35 - Weirdly shaped glacial icebergs) (see left), and as the current

picked up individual bergs, they moved rapidly towards the river's exit channel;

most however remained

stationary in majestic silence (see below left). Seals could be seen swimming around the lagoon

among the floating chunks of ice, their snouts just protruding from the water,

and Eider ducks bobbed around closer to the shore-line (see right). All of this was

happening against the backdrop of the great sweep of the Breiðamerkurjökull

glacier which loomed down from the higher ice-fields (Photo

36 - Breiðamerkurjökull glacier).

We spent another hour walking along the moraine slopes above the lagoon taking our photos. Remarkably,

despite the hordes of tourists who flock here in swarms, we managed to find

peace and seclusion in this western area of the Jökulsárlón lagoon to enjoy this

magnificent spectacle without disturbance or intrusion.

Ice 'diamonds' on Jökulsá River black sand beach:

back across the moraine fields, we crossed the Ring Road to walk the short stretch across the black sands down to the Ocean

shore-line by the Jökulsá River's outflow into the sea. Here the air was filled

with the booming roar of the mighty Atlantic surf which crashed onto the fine

black sand beach. But even more of a remarkable spectacle was the array Ice 'diamonds' on Jökulsá River black sand beach:

back across the moraine fields, we crossed the Ring Road to walk the short stretch across the black sands down to the Ocean

shore-line by the Jökulsá River's outflow into the sea. Here the air was filled

with the booming roar of the mighty Atlantic surf which crashed onto the fine

black sand beach. But even more of a remarkable spectacle was the array of

glacial ice chunks which had floated down the river from the Jökulsárlón lagoon

into the surf and now lay littered along the shore-line of black sand. Sparkling

in the hazy sunlight like huge diamonds laid out on a black velvet cushion,

these beach-stranded ice 'diamonds' made a noteworthy series of photographs

(Photo

37 - Jökulsárlón ice 'diamonds') (see right). of

glacial ice chunks which had floated down the river from the Jökulsárlón lagoon

into the surf and now lay littered along the shore-line of black sand. Sparkling

in the hazy sunlight like huge diamonds laid out on a black velvet cushion,

these beach-stranded ice 'diamonds' made a noteworthy series of photographs

(Photo

37 - Jökulsárlón ice 'diamonds') (see right).

Höfn Camping:

crossing the Jökulsá bridge, we began the 80kms final section of today's long

drive around the southern coastline towards Höfn (click

here for map of route). Route 1 initially crossed an area of vegetation-covered sandur before reaching farmland,

running between coast, where lines of breakers crashed onto the shore with a

constant distant roaring, and inland a backdrop of spectacular mountains capped by the ice-fields of Vatnajökull. The road now crossed the flat coastal

farmlands of Mýrar, backed by a hinterland graced with a mighty triple array of

glaciers, Skálafellsjökull,

Heinabergsjökull, and Fláajökull, with their

intervening nunataks (an Inuit word meaning exposed, jaggedly crested and ice-free rocky ridges

projecting above a glacier) of Hafrafell and Heinabergsfjöll. The Ring Road now turned northwards away from the

coast (see left and below right), to sweep more than 30kms around the bay of Hornafjörður. Finally down

Hornafjörður's eastern shore, Heinabergsjökull, and Fláajökull, with their

intervening nunataks (an Inuit word meaning exposed, jaggedly crested and ice-free rocky ridges

projecting above a glacier) of Hafrafell and Heinabergsfjöll. The Ring Road now turned northwards away from the

coast (see left and below right), to sweep more than 30kms around the bay of Hornafjörður. Finally down

Hornafjörður's eastern shore, we turned off onto Route 99 into the port-town of Höfn. Höfn

Camping was a large site along Hafnarbraut, tiered up the hillside, with what

seemed pleasant turfed areas for tent campers on the lower levels. We

found an area with power supplies on one of the higher gravelled tiers, and with

some difficulty managed to level George with his chocks. The view from this

higher position, looking across the town outskirts in the now bright late

afternoon sunshine, was simply stunning (see below left) (Photo

38 - Höfn Camping mountain vista), with a northward 180º skyline of

mountain peaks and ridges, graced with intervening glaciers and all topped by Vatnajökull's

snowfields. But the price of facing out across this spectacular outlook was that

a chill northerly wind now blew directly into the open slider. we turned off onto Route 99 into the port-town of Höfn. Höfn

Camping was a large site along Hafnarbraut, tiered up the hillside, with what

seemed pleasant turfed areas for tent campers on the lower levels. We

found an area with power supplies on one of the higher gravelled tiers, and with

some difficulty managed to level George with his chocks. The view from this

higher position, looking across the town outskirts in the now bright late

afternoon sunshine, was simply stunning (see below left) (Photo

38 - Höfn Camping mountain vista), with a northward 180º skyline of

mountain peaks and ridges, graced with intervening glaciers and all topped by Vatnajökull's

snowfields. But the price of facing out across this spectacular outlook was that

a chill northerly wind now blew directly into the open slider.

Having pitched, we walked down to book

in. As at all the campsites along Iceland's southern coast cashing in on a

seemingly insatiable tourist demand,

prices

were greed-driven and unduly expensive: adults 1,650kr,

power 750kr, and 2 minute showers 50kr, making a total of 4,150kr; we managed to

negotiate a seniors' discount of 3,450kr. But despite the high charges,

facilities were basic, totally inadequate given the

size of the campsite, and with disgraceful showers. As dusk and darkness fell mid-evening, huge numbers of

hire-campers, camping-cars and hire-cars flooded in, with traffic

driving around in search were greed-driven and unduly expensive: adults 1,650kr,

power 750kr, and 2 minute showers 50kr, making a total of 4,150kr; we managed to

negotiate a seniors' discount of 3,450kr. But despite the high charges,

facilities were basic, totally inadequate given the

size of the campsite, and with disgraceful showers. As dusk and darkness fell mid-evening, huge numbers of

hire-campers, camping-cars and hire-cars flooded in, with traffic

driving around in search of a space and constant slamming of car doors until

gone 11-00pm, along with the noise of traffic along the main road; if you stay

at Höfn Camping, even in September, don't expect to get any sleep! It was one of

the most overcrowded and noisy campsites we had stayed at, and with its unduly

expensive prices and sub-standard facilities, only the magnificent setting saved Höfn

Camping from being given the lowest negative rating. of a space and constant slamming of car doors until

gone 11-00pm, along with the noise of traffic along the main road; if you stay

at Höfn Camping, even in September, don't expect to get any sleep! It was one of

the most overcrowded and noisy campsites we had stayed at, and with its unduly

expensive prices and sub-standard facilities, only the magnificent setting saved Höfn

Camping from being given the lowest negative rating.

Visit to Höfn harbour:

we were woken early, not by our alarm, but yet again by the noise of slamming

car doors and loud shouting from un-neighbourly nearby tent campers. Fortunately

the campsite emptied quite quickly, leaving us to enjoy a peaceful morning; the

sun shone brightly in a clear blue sky, but with the keen, northerly wind still

blowing. Perched at the tip of a narrow neck of land extending out into the

stormy Atlantic, Höfn is now the main town and only port along this part of the

south coast; today we should take a walk around the harbour and the Ósland

marshes and peninsula out towards the coast. The town only began to develop in

the late 19th~early 20th centuries as a trading centre for the farms

scattered

along the south coast; its name Höfn meaning Harbour is derived from being sited

at this coastline's only natural harbour and deep water anchorage,

though the harbour needs regular dredging to prevent silting up.

Expansion followed with the 1950s fishing boom and the establishment of a fish

processing and freezing factory, still the town's major employer. These days lobster has scattered

along the south coast; its name Höfn meaning Harbour is derived from being sited

at this coastline's only natural harbour and deep water anchorage,

though the harbour needs regular dredging to prevent silting up.

Expansion followed with the 1950s fishing boom and the establishment of a fish

processing and freezing factory, still the town's major employer. These days lobster has become the main luxury catch at Höfn, selling at unimaginably high prices in

local restaurants. Tourism has also increasingly become a mainstay of the local

economy.

become the main luxury catch at Höfn, selling at unimaginably high prices in

local restaurants. Tourism has also increasingly become a mainstay of the local

economy.

We drove down the main street, Hafnarbraut, to its

end at the large harbour where a few boats, including the local lifeboat, were

moored (see above right) (Photo

39 - Höfn harbour). Nearby in a prime position by the harbour front, Gamlabúð

(meaning Old

Shop), an attractively refurbished 1864 wooden warehouse, which had once been the original

trading centre's shop, now serves as Höfn's Visitor Centre and Exhibition on Vatnajökull

National Park. The Exhibition was not only free entry but, to our delight, was

also showing the 1996 documentary film on the Grimsvötn sub-glacial eruption and

disastrous jökulhlaup which had washed away a section of the Ring Road,

destroying the main bridge at Skeiðarársandur. The film included wonderful

aerial footage, filmed at great

hazard to aircraft and pilot, of the Grimsvötn

eruption, the build-up of sub-glacial melt-water, and eventual burst-out of the

flood. It also included incredible footage of the jökulhlaup's destructive

tsunami across the Skeiðarársandur outwash-plain, smashing its way through the

Ring Road and toppling the bridge like matchwood, with house-sized chunks of ice hazard to aircraft and pilot, of the Grimsvötn

eruption, the build-up of sub-glacial melt-water, and eventual burst-out of the

flood. It also included incredible footage of the jökulhlaup's destructive

tsunami across the Skeiðarársandur outwash-plain, smashing its way through the

Ring Road and toppling the bridge like matchwood, with house-sized chunks of ice weighing 100s of tons borne along by the flood. We expressed our thanks to the

attendant for having this valuable archive film available here, when it was no

longer shown at the tourist-oriented Skaftafell Visitor Centre. She even taught

us how to pronounce the Icelandic word jökulhlaup, something like

Yer-kul-hleup. But even with our earnest practising, the Icelandic au

diphthong is a sound we simply do not have in English, sounding more like the

French eu in feuille.

weighing 100s of tons borne along by the flood. We expressed our thanks to the

attendant for having this valuable archive film available here, when it was no

longer shown at the tourist-oriented Skaftafell Visitor Centre. She even taught

us how to pronounce the Icelandic word jökulhlaup, something like

Yer-kul-hleup. But even with our earnest practising, the Icelandic au

diphthong is a sound we simply do not have in English, sounding more like the

French eu in feuille.

Coastal walk around Ósland marshes: having eaten our lunch

sandwiches by the harbour side, we set off to walk the footpath around the

marshes of the Ósland peninsula down at the coast. In the clear light of a sunny

day, the landward panorama northward across the Hornafjörður lagoon was

absolutely stunning (see above left), with an array of four glaciers, left to

right Skálafellsjökull, Heinabergsjökull, Fláajökull

and Hoffellsjökull, gracing the

mountainous skyline,

and Fláajökull's full length

sweeping down to the coast (see above right) (Photo

40 - Hornafjörður vista of Fláajökull). To the eastward beyond the

harbour, across the width of Skarðsfjörður, the jagged ridges of Vestrahorn

descended to the coast (see above left) where Stokksnes lighthouse was just visible. We followed the footpath alongside a small bay off Hornafjörður

with the mountainous and glacier-strewn panorama becoming even more dramatic mountainous skyline,

and Fláajökull's full length

sweeping down to the coast (see above right) (Photo

40 - Hornafjörður vista of Fláajökull). To the eastward beyond the

harbour, across the width of Skarðsfjörður, the jagged ridges of Vestrahorn

descended to the coast (see above left) where Stokksnes lighthouse was just visible. We followed the footpath alongside a small bay off Hornafjörður

with the mountainous and glacier-strewn panorama becoming even more dramatic

(see above right) (Photo

41 - Glacier-strewn panorama). Out onto the tip of the grassy peninsula with its central marshy pond,

all

the Arctic Terns which nest here in the tufty grass in early summer had long

since departed for their long migration to the Antarctic; you would need a hard

hat to walk out here earlier in the year to protect your head from aerial attack

by the Terns defending their nests and young. But at this late stage of the

summer, there was little bird-life to be seen other than a few Eiders as we

followed the path around the outer side of the peninsula. What we could hear