|

CAMPING

IN SWEDEN 2013 - Skåne, Göteborg, the Bohuslän Coast, and inland to Trollhättan, Lake Vänern

and Dalsland: CAMPING

IN SWEDEN 2013 - Skåne, Göteborg, the Bohuslän Coast, and inland to Trollhättan, Lake Vänern

and Dalsland:

Despite DFDS' monopolistic prices, we again

this year crossed the North Sea using their Harwich\Esbjerg service to Denmark (Photo 1 - Ferry entering Esbjerg harbour); a newspaper headline in the ferry's shop gave symbolic

representation of why we were again thankful to be saying farewell to UK for a

while: Commons Deputy Speaker arrested on charges of gay rape (sic!). An

afternoon's drive brought us the width of Denmark's 3 main islands across the

spectacular bridges (Photo 2 - Crossing the Store Bælt Bridge) and that

first evening we finally crossed the Öresund Bridge for our first camp in this

year's host country near to Lomma just north of Malmö, with the song of this

year's first cuckoo echoing around the shore-side campsite and supper looking out to

a glowing sunset across the Öresund (Photo

3 - Sunset over the Öresund).

University and Cathedral city of Lund:

on a serenely sunny Spring morning, we drove

into nearby Lund; experience of finding a parking place taught us an essential

Swedish word avgift meaning charge or payment by the hour. Lund is

Sweden's 2nd oldest city founded by the Danish-Viking King Sven Tveskägg (Forkbeard)

in 990 AD and is now a lively university town with racks of students' bicycles lining the

main square of Stortorget (Photo 4 - Lund's main square, Stortorget). We

spent a happy morning ambling around the flower and vegetable market,

lunching in the market-hall and visiting the excavated subterranean remains of

Lund's medieval churches. Along Kyrkogatan we reached the twin-towered

Cathedral, the Domkyrkan built in the 12th century when Lund became

Scandinavia's first independent archbishopric (see left). University and Cathedral city of Lund:

on a serenely sunny Spring morning, we drove

into nearby Lund; experience of finding a parking place taught us an essential

Swedish word avgift meaning charge or payment by the hour. Lund is

Sweden's 2nd oldest city founded by the Danish-Viking King Sven Tveskägg (Forkbeard)

in 990 AD and is now a lively university town with racks of students' bicycles lining the

main square of Stortorget (Photo 4 - Lund's main square, Stortorget). We

spent a happy morning ambling around the flower and vegetable market,

lunching in the market-hall and visiting the excavated subterranean remains of

Lund's medieval churches. Along Kyrkogatan we reached the twin-towered

Cathedral, the Domkyrkan built in the 12th century when Lund became

Scandinavia's first independent archbishopric (see left).

|

Click on 2 highlighted areas of map for

details of

SW Sweden |

|

The interior with its sturdy

Romanesque rounded arches is dominated by the chancel's huge apse whose dome is

decorated with gilded mosaics of Christ in Glory (Photo 5 - Lund Cathedral apse with gilded mosaics).

Down in the gloomy crypt, 2 of the pillars supporting the chancel above are

gripped by stone figures: the legend is that Finn the Giant built the cathedral

for St Lawrence demanding the saint's eyes in payment unless the saint could

guess his name. The canny saint however overheard the giant's wife boast to her

child of Father Finn's gift of eyes to play with; the giant, his wife and child rushed into

the crypt to pull down the columns but were turned to stone. It's a good yarn,

and they are still they to be seen clutching the pillars. Up in the nave, the 1440s

astronomical clock with its complex of dials plays In Dulce

Jubilo as the clock strikes 3-00 and a procession of Wise Men carved figures parades around

the Virgin and Child. The interior with its sturdy

Romanesque rounded arches is dominated by the chancel's huge apse whose dome is

decorated with gilded mosaics of Christ in Glory (Photo 5 - Lund Cathedral apse with gilded mosaics).

Down in the gloomy crypt, 2 of the pillars supporting the chancel above are

gripped by stone figures: the legend is that Finn the Giant built the cathedral

for St Lawrence demanding the saint's eyes in payment unless the saint could

guess his name. The canny saint however overheard the giant's wife boast to her

child of Father Finn's gift of eyes to play with; the giant, his wife and child rushed into

the crypt to pull down the columns but were turned to stone. It's a good yarn,

and they are still they to be seen clutching the pillars. Up in the nave, the 1440s

astronomical clock with its complex of dials plays In Dulce

Jubilo as the clock strikes 3-00 and a procession of Wise Men carved figures parades around

the Virgin and Child.

Outside

in the Lundagård university park, students sat on the grass in the sunshine (see

left), as

we walked through to the beautiful botanical gardens of the Universitets platsen,

with the magnolias now in full bloom and the glorious classically styled

Universitets huset forming a backdrop to the grand central fountain (Photo 6 - Main building and gardens of Lund University).

Lund University

was founded in 1666 after the 1658 crucial Treaty of Roskilde

had finally ceded the SW corner of the country to Sweden from Danish control.

The university developed in the 19th century with the establishment of new

Chairs, an increase in student numbers and women admitted as early as the 1880s. In 1900

there were 1000 students at Lund; today it is one of Scandinavia's largest

institutions of higher education and research with over 47,000 students. Inside

the university building we were able to get a look at the magnificent

assembly aula where degree ceremonies are held (see left). was founded in 1666 after the 1658 crucial Treaty of Roskilde

had finally ceded the SW corner of the country to Sweden from Danish control.

The university developed in the 19th century with the establishment of new

Chairs, an increase in student numbers and women admitted as early as the 1880s. In 1900

there were 1000 students at Lund; today it is one of Scandinavia's largest

institutions of higher education and research with over 47,000 students. Inside

the university building we were able to get a look at the magnificent

assembly aula where degree ceremonies are held (see left).

Helsingborg, port for cross-Öresund ferries: 30kms north we reached

the industrial port of Helsingborg planning to stay at Råå Vallar Camping, yet

another wretched holiday-camp where we were greeted in an unwelcoming and

officious manner: it was one of those places with so many offensively

restrictive regulations, you did not know which one to break first, an expensive

and inhospitable place to be avoided. The following morning we drove down to the harbour from where

ferries chug back and forth across the Öresund carrying Swedes across to

Helsingør on the Danish side to buy cheaper alcohol (see right). But today the

Danish shore was scarcely visible in miserable misty rain.

We sat by the yacht marina looking across to Helsingborg's Kulturhus, the city

Museum and Art Gallery designed by Kim Utzon, son of the Sydney Opera House

architect, but a rather less inspiring design. The Kulturhus was funded by the

foundation set up by Henry Dunkers, a Helsingborg industrialist who made his

fortune by perfecting the vulcanising process to make rubber boots, manufactured at the

Helsingborg Gummifabrik. The factory closed in 1979 but the name lives on in the

modernistic building by the city's waterfront. Rather more imposing is the

city's pompously Neo-Gothic Rådhus (town hall) which dominates the corner Helsingborg, port for cross-Öresund ferries: 30kms north we reached

the industrial port of Helsingborg planning to stay at Råå Vallar Camping, yet

another wretched holiday-camp where we were greeted in an unwelcoming and

officious manner: it was one of those places with so many offensively

restrictive regulations, you did not know which one to break first, an expensive

and inhospitable place to be avoided. The following morning we drove down to the harbour from where

ferries chug back and forth across the Öresund carrying Swedes across to

Helsingør on the Danish side to buy cheaper alcohol (see right). But today the

Danish shore was scarcely visible in miserable misty rain.

We sat by the yacht marina looking across to Helsingborg's Kulturhus, the city

Museum and Art Gallery designed by Kim Utzon, son of the Sydney Opera House

architect, but a rather less inspiring design. The Kulturhus was funded by the

foundation set up by Henry Dunkers, a Helsingborg industrialist who made his

fortune by perfecting the vulcanising process to make rubber boots, manufactured at the

Helsingborg Gummifabrik. The factory closed in 1979 but the name lives on in the

modernistic building by the city's waterfront. Rather more imposing is the

city's pompously Neo-Gothic Rådhus (town hall) which dominates the corner

opposite the ferry harbour (Photo 7 - Waterfront and Rådhus at Helsingborg).

The elongated main square of Stortorget leads uphill from the port to the

remains of Helsingborg's medieval castle, fought over for centuries until Sweden

finally gained control of Skåne from the Danes. The surviving castle keep of

Kärnan now serves as a landmark for mariners passing along the Öresund and

provides spectacular views down to the ferry harbour,

at least on a clear day which today wasn't! (Photo 8 - Öresund ferry from Helsinør entering Helsingborg harbour).

From the parklands surrounding Kärnan, a pathway lined with rhododendrons leads

down to Södra Storgatan in the old town and the Danish-Gothic basilica of Sancta

Maria kyrka. The red-brick 14th century church's plain exterior gives little

impression of its beautiful interior. Amid the imposing brick-archwork, the eye

is drawn to the gilded 1450 carved triptych, its 3 panels depicting scenes from

the life of Christ (see left). opposite the ferry harbour (Photo 7 - Waterfront and Rådhus at Helsingborg).

The elongated main square of Stortorget leads uphill from the port to the

remains of Helsingborg's medieval castle, fought over for centuries until Sweden

finally gained control of Skåne from the Danes. The surviving castle keep of

Kärnan now serves as a landmark for mariners passing along the Öresund and

provides spectacular views down to the ferry harbour,

at least on a clear day which today wasn't! (Photo 8 - Öresund ferry from Helsinør entering Helsingborg harbour).

From the parklands surrounding Kärnan, a pathway lined with rhododendrons leads

down to Södra Storgatan in the old town and the Danish-Gothic basilica of Sancta

Maria kyrka. The red-brick 14th century church's plain exterior gives little

impression of its beautiful interior. Amid the imposing brick-archwork, the eye

is drawn to the gilded 1450 carved triptych, its 3 panels depicting scenes from

the life of Christ (see left).

Kullaberg Peninsula Nature Reserve:

rising conspicuously above the flat surrounding farmland, the high wooded ridge

of the Kullaberg Peninsula was our next stop with a stay at First Camp

Möllehässle; despite the high price at what was another large holiday-camp, the

setting was pleasant with flat pitches terraced into the grassy slopes and more

importantly, a hospitable welcome; what a difference a smile makes! That evening

we enjoyed the trip's first barbecue (see right). Our reason however for coming here was a day's walking around the Kullaberg Nature

Reserve's cliff-top paths of the peninsula which projects into the Kattegat. Kullaberg Peninsula Nature Reserve:

rising conspicuously above the flat surrounding farmland, the high wooded ridge

of the Kullaberg Peninsula was our next stop with a stay at First Camp

Möllehässle; despite the high price at what was another large holiday-camp, the

setting was pleasant with flat pitches terraced into the grassy slopes and more

importantly, a hospitable welcome; what a difference a smile makes! That evening

we enjoyed the trip's first barbecue (see right). Our reason however for coming here was a day's walking around the Kullaberg Nature

Reserve's cliff-top paths of the peninsula which projects into the Kattegat.

Parking by the lighthouse at the tip of the peninsula, we set off around the

woodland path and were soon down on hands and knees photographing the banks of Spring wild flora, most

noticeably wood anemones (Photo 9 - Banks of

Wood Anemones at Kullaberg Nature Reserve).

Kullaberg's distinctive peninsula is an ancient east-west ridge of

erosion-resistant gneiss bedrock formed by the surrounding softer red sandstone

being eroded away and criss-crossed with fissure ravines along the coastlines.

The path undulated through the delightful birch woodland with occasional

glimpses of the sheer rocky cliffs. Across to the southern coastline among tall

birch trees whose bright green new leaf glowed in the sunlight, the return path

passed over more open heathland back to the lighthouse (see left) where the rocks at the

peninsula's tip gave misty views out across the Kattegat (Photo 10 - Misty Kattegat vista

from Kullaberg lighthouse). Parking by the lighthouse at the tip of the peninsula, we set off around the

woodland path and were soon down on hands and knees photographing the banks of Spring wild flora, most

noticeably wood anemones (Photo 9 - Banks of

Wood Anemones at Kullaberg Nature Reserve).

Kullaberg's distinctive peninsula is an ancient east-west ridge of

erosion-resistant gneiss bedrock formed by the surrounding softer red sandstone

being eroded away and criss-crossed with fissure ravines along the coastlines.

The path undulated through the delightful birch woodland with occasional

glimpses of the sheer rocky cliffs. Across to the southern coastline among tall

birch trees whose bright green new leaf glowed in the sunlight, the return path

passed over more open heathland back to the lighthouse (see left) where the rocks at the

peninsula's tip gave misty views out across the Kattegat (Photo 10 - Misty Kattegat vista

from Kullaberg lighthouse).

So pleasing were the wild flora during these

first 3 weeks that we have included a photo-gallery of

Spring flora of SW Sweden

Göteborg,

Sweden's second city: a 200km drive up the E6 motorway brought us to

Sweden's second city, Göteborg (pronounced Yerteboy). The city's only

campsites are both run by the horrendous Liseberg Amusement Park, both of them huge

holiday-camps charging outrageously extortionate prices for the dubious

privilege of staying there. We did however want to visit Göteborg and chose the

marginally lower priced Askim Strand Camping some 12kms out of the city down at

the coast. The young staff however were welcoming and helpful, giving us

details of the Rosa Express buses into the city centre and the bus stop 15

minutes walk away. The following morning, we set off to catch the bus,

following the journey on the street plan we had been given to get off at the

city's Central Railway Station. Göteborg was

founded at the mouth of the Göta River in 1621 by King Gustav II Adolphus. With

the South-West of the country securely in Swedish control from the Danes after

1658, the port-city developed as a major trading post bypassing the extortionate Öresund tolls charged by the Danish and so attracting British, Dutch and German

merchants. In the 18/19th centuries it Göteborg,

Sweden's second city: a 200km drive up the E6 motorway brought us to

Sweden's second city, Göteborg (pronounced Yerteboy). The city's only

campsites are both run by the horrendous Liseberg Amusement Park, both of them huge

holiday-camps charging outrageously extortionate prices for the dubious

privilege of staying there. We did however want to visit Göteborg and chose the

marginally lower priced Askim Strand Camping some 12kms out of the city down at

the coast. The young staff however were welcoming and helpful, giving us

details of the Rosa Express buses into the city centre and the bus stop 15

minutes walk away. The following morning, we set off to catch the bus,

following the journey on the street plan we had been given to get off at the

city's Central Railway Station. Göteborg was

founded at the mouth of the Göta River in 1621 by King Gustav II Adolphus. With

the South-West of the country securely in Swedish control from the Danes after

1658, the port-city developed as a major trading post bypassing the extortionate Öresund tolls charged by the Danish and so attracting British, Dutch and German

merchants. In the 18/19th centuries it

became the base for Swedish trade with

the Far East monopolised by the Swedish East India Company, and continues as a

major cosmopolitan port-city today with a population of over 500,000. became the base for Swedish trade with

the Far East monopolised by the Swedish East India Company, and continues as a

major cosmopolitan port-city today with a population of over 500,000.

We quickly got our bearing and began our walk around the city at the Central

Station whose surviving period façade reflects its 1856 foundation, the

country's oldest railway station, with stylish ticket hall to match (see right).

In the brashly garish Nordstan shopping centre opposite, the fluently

English- speaking staff in the TIC answered our questions with helpful

efficiency, adding to our stock of Swedish language for good measure. Following

the embankment of the Rosenlunds-kanalen, the former moat of the original

fortified city, we walked around past the buildings of Göteborg University where

city trams trundled to and fro across the bridge (Photo 11 - Göteborg tram crossing Rosenlunds-kanalen).

Nearby we came to Stora Saluhallen, a grand barrel-roofed structure dating from

the 1880s housing the city's wonderful indoor market (see left). Now regular

readers of our travels will know that ambling around markets is one of our

favourite pastimes, and Göteborg Saluhallen did not disappoint (Photo 12 - Göteborg's Stora Saluhallen market-hall).

This was a busy and wonderfully atmospheric market and we happily browsed the

butchery, vegetable and cheese stalls along with local shoppers; the

appetising food stalls were an obvious lunch venue for good value bowls of tasty speaking staff in the TIC answered our questions with helpful

efficiency, adding to our stock of Swedish language for good measure. Following

the embankment of the Rosenlunds-kanalen, the former moat of the original

fortified city, we walked around past the buildings of Göteborg University where

city trams trundled to and fro across the bridge (Photo 11 - Göteborg tram crossing Rosenlunds-kanalen).

Nearby we came to Stora Saluhallen, a grand barrel-roofed structure dating from

the 1880s housing the city's wonderful indoor market (see left). Now regular

readers of our travels will know that ambling around markets is one of our

favourite pastimes, and Göteborg Saluhallen did not disappoint (Photo 12 - Göteborg's Stora Saluhallen market-hall).

This was a busy and wonderfully atmospheric market and we happily browsed the

butchery, vegetable and cheese stalls along with local shoppers; the

appetising food stalls were an obvious lunch venue for good value bowls of tasty

fish-soup. Göteborg's indoor 1874

fish-market, the Feskekörka, is an attractive curiosity resembling externally a

Neo-Gothic church (see right). The only worship here however is of fish, fish

and more fish, stalls laden with every kind of fish and shellfish; it was a

sight and smell to delight any fish-loving palate (Photo 13 - Feskekôrka indoor fish market). fish-soup. Göteborg's indoor 1874

fish-market, the Feskekörka, is an attractive curiosity resembling externally a

Neo-Gothic church (see right). The only worship here however is of fish, fish

and more fish, stalls laden with every kind of fish and shellfish; it was a

sight and smell to delight any fish-loving palate (Photo 13 - Feskekôrka indoor fish market).

Passing

all the trendy and overpriced bars and restaurants along the wide boulevard of

Avenyn, we followed the regally named Vasa-gatan to a park by the church of

Hagakyrka and the memorial to Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish businessman-diplomat

who rescued 1000s of Hungarian Jews from certain death at German hands in 1944

and who mysteriously disappeared after the 1945 Soviet 'liberation' of Budapest.

Youngsters lolled on the grass or played ball games, indifferent to the

distinctive monolith engraved with Wallenberg's portrait and small figures of

Jewish victims squatting forlornly at the base of the memorial (see left).

Returning through the parkland opposite the university where students picnicked

on the grass beside the canal, we walked up Västra Hamngatan to Göteborg Cathedral,

the Domkyrkan (see right). The original church was built soon after Gustav II Adolphus' foundation of the city and was dedicated in 1633 as the diocesan

cathedral of Western Sweden. The present church dating from 1827 is the third on

the site, the first 2 having been destroyed by fires; fronted at the west end

portico by 4 huge sandstone columns, the beige exterior brickwork is matched by

even more starkly plain Lutheran interior. The only concession to adornment is

the ornately gilded post-resurrection empty cross with Christ's grave clothes

scattered around. Passing

all the trendy and overpriced bars and restaurants along the wide boulevard of

Avenyn, we followed the regally named Vasa-gatan to a park by the church of

Hagakyrka and the memorial to Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish businessman-diplomat

who rescued 1000s of Hungarian Jews from certain death at German hands in 1944

and who mysteriously disappeared after the 1945 Soviet 'liberation' of Budapest.

Youngsters lolled on the grass or played ball games, indifferent to the

distinctive monolith engraved with Wallenberg's portrait and small figures of

Jewish victims squatting forlornly at the base of the memorial (see left).

Returning through the parkland opposite the university where students picnicked

on the grass beside the canal, we walked up Västra Hamngatan to Göteborg Cathedral,

the Domkyrkan (see right). The original church was built soon after Gustav II Adolphus' foundation of the city and was dedicated in 1633 as the diocesan

cathedral of Western Sweden. The present church dating from 1827 is the third on

the site, the first 2 having been destroyed by fires; fronted at the west end

portico by 4 huge sandstone columns, the beige exterior brickwork is matched by

even more starkly plain Lutheran interior. The only concession to adornment is

the ornately gilded post-resurrection empty cross with Christ's grave clothes

scattered around.

We continued north to Stenpiren (Stone Pier)

overlooking the wide Göta River with the city port's cranes lining the far bank.

Here on the quayside stands the Delaware Monument, a replica of the memorial set

up in America to the first Swedish emigrants who set off from here to find a new

life in 'New Sweden' on the banks of the Delaware River in 1638 (see left). Many 1000s of

Swedish emigrants followed fleeing the famines of the 19th century. Along the

embankment of Norra Hamngatan, we passed the Stadmuseum housed in what was once

the HQ and customs house of the Swedish East India Company whose affluence was

based on its monopolistic mercantile rights with the Far East on condition that

all its trading goods were auctioned here in Göteborg. The port-city also

prospered from this until competition from British and Dutch tea and spice

traders broke the monopoly. Just beyond we reached Gustav Adolfs We continued north to Stenpiren (Stone Pier)

overlooking the wide Göta River with the city port's cranes lining the far bank.

Here on the quayside stands the Delaware Monument, a replica of the memorial set

up in America to the first Swedish emigrants who set off from here to find a new

life in 'New Sweden' on the banks of the Delaware River in 1638 (see left). Many 1000s of

Swedish emigrants followed fleeing the famines of the 19th century. Along the

embankment of Norra Hamngatan, we passed the Stadmuseum housed in what was once

the HQ and customs house of the Swedish East India Company whose affluence was

based on its monopolistic mercantile rights with the Far East on condition that

all its trading goods were auctioned here in Göteborg. The port-city also

prospered from this until competition from British and Dutch tea and spice

traders broke the monopoly. Just beyond we reached Gustav Adolfs  Torg, where

the city founder's grand statue stood in the centre of His Square; imperiously he

pointed to the spot where he wished his new city to be built - Right here, His

Majesty declared. Apparently the original statue commissioned from Germany was

kidnapped on its way to Sweden; rather than pay the ransom, the city merchant-venturers

simply ordered a new one, and here it stood in its eponymous square waiting to

be photographed (Photo 14 - Göteborg's founder King Gustav II Adolphus). Torg, where

the city founder's grand statue stood in the centre of His Square; imperiously he

pointed to the spot where he wished his new city to be built - Right here, His

Majesty declared. Apparently the original statue commissioned from Germany was

kidnapped on its way to Sweden; rather than pay the ransom, the city merchant-venturers

simply ordered a new one, and here it stood in its eponymous square waiting to

be photographed (Photo 14 - Göteborg's founder King Gustav II Adolphus).

On from here it was a short walk to the Lilla Bomman harbour,

now the city marina,

where the city's modernistic Opera House stood by the waterside. On the far side

a huge steel hulled sailing clipper was moored, over shadowed by the 86m high

lipstick-shaped tower block landmark of Utkiken (Photo 15 - Lilla Bommen Harbour and Utkiken tower).

Further round the harbour frontage, we reached the Maritime Museum's collection

of 20th century steamers, lightship, naval destroyer and tiny submarine the

Nordkapen all moored along the harbour-side, backed by the imposing building

of the port-city's Navigation School (see right). This is topped by its time-ball by which

ships' navigators set their chronometers. After such a fulfilling day in Göteborg,

we plodded back to the Nordstan Centre to catch our bus back out to the campsite

Kungälv

- Bohus Fästning medieval fortress, and a good campsite at last: we moved 12 kms north to the small town of Kungälv

where, on an island between the Rivers Göta and Nordre, Bohus Fästning

(Fortress) was built in 1308 by King Håkon V Magnusson of Norway to guard what

was then the southern border of his realm at its meeting point with the medieval

kingdoms of Sweden and Denmark. It was one of the mightiest castles in the Nordic lands, besieged 14 times but

never taken, and standing below its formidable walls, you could understand why.

Occupied by both the Norwegians and Danes during the first 350 years of its

existence Kungälv

- Bohus Fästning medieval fortress, and a good campsite at last: we moved 12 kms north to the small town of Kungälv

where, on an island between the Rivers Göta and Nordre, Bohus Fästning

(Fortress) was built in 1308 by King Håkon V Magnusson of Norway to guard what

was then the southern border of his realm at its meeting point with the medieval

kingdoms of Sweden and Denmark. It was one of the mightiest castles in the Nordic lands, besieged 14 times but

never taken, and standing below its formidable walls, you could understand why.

Occupied by both the Norwegians and Danes during the first 350 years of its

existence

as

both a military stronghold and royal palace, it finally became Swedish under the

1658 Treaty of Roskilde. By the end of the 18th century with its military

significance past, troops were withdrawn and the castle abandoned; locals from Kungälv

plundered the ruins for building stone. Restoration began in the late 19th

century when the castle's historical worth was recognised. Its imposing remains

stand to this day and we spent the afternoon scrambling around the preserved

ruins of the fortress round tower and ramparts (see left) (Photo 16 - 14th century fortress at Kungälv).

Immediately opposite, we found tonight's base, the Kungälvs Vandrarhem (hostel)

and Camping (see right), a hospitable and straightforward little campsite in a

splendid riverbank setting overshadowed by Bohus castle. It had everything that

other campsites used so far had lacked: a peaceful setting free from noisy

holiday-makers, a lovely welcome, free wi-fi internet and very reasonable price,

a real little gem of a site. And we only discovered afterwards that Kungälv,

just 12 kms north of Göteborg, is also on a regular express bus route into the

city; we could have made our visit to Göteborg from here, staying at Kungälvs

Vandrarhem for almost half the price of the unsavoury Liseberg Askim Strand. as

both a military stronghold and royal palace, it finally became Swedish under the

1658 Treaty of Roskilde. By the end of the 18th century with its military

significance past, troops were withdrawn and the castle abandoned; locals from Kungälv

plundered the ruins for building stone. Restoration began in the late 19th

century when the castle's historical worth was recognised. Its imposing remains

stand to this day and we spent the afternoon scrambling around the preserved

ruins of the fortress round tower and ramparts (see left) (Photo 16 - 14th century fortress at Kungälv).

Immediately opposite, we found tonight's base, the Kungälvs Vandrarhem (hostel)

and Camping (see right), a hospitable and straightforward little campsite in a

splendid riverbank setting overshadowed by Bohus castle. It had everything that

other campsites used so far had lacked: a peaceful setting free from noisy

holiday-makers, a lovely welcome, free wi-fi internet and very reasonable price,

a real little gem of a site. And we only discovered afterwards that Kungälv,

just 12 kms north of Göteborg, is also on a regular express bus route into the

city; we could have made our visit to Göteborg from here, staying at Kungälvs

Vandrarhem for almost half the price of the unsavoury Liseberg Askim Strand.

The Bohuslän

Coast - Marstrand: on

a rainy, blustery morning with a chill westerly wind blowing off the sea, we

drove out to the Bohuslän Coast, crossing causeways and an elegantly arched bridge

connecting a chain of islets ending at the island of Koön where the chain-ferry

connected to the car-free off-shore island of Marstrand. Marstrands Familje

Camping 1km inland from the ferry was totally deserted in early May, but the

owner responded to our phone call with the barrier key code; thankful to be away

from overcrowded holiday-camps, we relished another sensibly priced, welcoming

and peaceful campsite in a lovely rural setting and with free internet. A

peculiar Swedish dietary habit is their passion for meat balls (köttbullar), and

that evening as a warming antidote to the driving rain and cutting wind, we cooked our

first sample of köttbullar in tomato sauce with spaghetti, doubtless not the

Swedish way but it has now become our way! The following morning, we crossed by The Bohuslän

Coast - Marstrand: on

a rainy, blustery morning with a chill westerly wind blowing off the sea, we

drove out to the Bohuslän Coast, crossing causeways and an elegantly arched bridge

connecting a chain of islets ending at the island of Koön where the chain-ferry

connected to the car-free off-shore island of Marstrand. Marstrands Familje

Camping 1km inland from the ferry was totally deserted in early May, but the

owner responded to our phone call with the barrier key code; thankful to be away

from overcrowded holiday-camps, we relished another sensibly priced, welcoming

and peaceful campsite in a lovely rural setting and with free internet. A

peculiar Swedish dietary habit is their passion for meat balls (köttbullar), and

that evening as a warming antidote to the driving rain and cutting wind, we cooked our

first sample of köttbullar in tomato sauce with spaghetti, doubtless not the

Swedish way but it has now become our way! The following morning, we crossed by the little ferry which chugs back and forth across the narrow sound separating Marstrand from its neighbouring island, for the 6km walk around Marstrand's

shore-side footpath. The crossing takes just a couple of minutes, and in warm

clothes and full waterproofs against the chill wind, we set off along the

waterfront passing the little harbour's wooden houses which might have looked so

attractive in fine weather. But the Nordic gods were smiling on us today and by

the time we left the town behind and headed around the rocky coastline, the

cloud was starting to break. Being a safe and ice-free port, Marstrand had once

prospered from the herring-fishing

industry, but the herring disappeared taking with them the island's source of

prosperity. In the 19th century Marstrand's wooden fish-salting

the little ferry which chugs back and forth across the narrow sound separating Marstrand from its neighbouring island, for the 6km walk around Marstrand's

shore-side footpath. The crossing takes just a couple of minutes, and in warm

clothes and full waterproofs against the chill wind, we set off along the

waterfront passing the little harbour's wooden houses which might have looked so

attractive in fine weather. But the Nordic gods were smiling on us today and by

the time we left the town behind and headed around the rocky coastline, the

cloud was starting to break. Being a safe and ice-free port, Marstrand had once

prospered from the herring-fishing

industry, but the herring disappeared taking with them the island's source of

prosperity. In the 19th century Marstrand's wooden fish-salting

sheds were

converted into bathing houses and the little port re-invented itself as a fashionable

bathing resort. Today the port attracts the affluent yachting hoards in summer

but in early May the town was a quiet sleepy place with the harbour side

restaurants just beginning to prepare for summer influx of tourists. The

footpath sloped up past glorious banks of cowslips (see right) onto the cliff-tops

overlooking the sound with a side path branching down through a narrow squeeze

in high rocks, and we wound a slippery way among the rocks to the craggy

shore-line where eider ducks bobbed in the water with their characteristic 'oo-ing'

sound and terns flitted overhead making their piercing alarm calls. As we

rounded the island's western tip with its small lighthouse, the sun miraculously

broke through but with the SW wind still blowing briskly chill

(Photo 17 - Marstrand's rocky shoreline). We

followed the path over the shore-side rocks revelling in the glorious light

sparkling across the sea (see left), eventually completing the circuit back into the

southern end of Marstrand town by the sound to walk along the harbour front past

the wooden houses (Photo 18 - Wooden houses along Marstrand's waterfront).

We joined local people returning by the ferry across the sound, and walked back

to camp after such a glorious day's walk around Marstrand's rocky shore. sheds were

converted into bathing houses and the little port re-invented itself as a fashionable

bathing resort. Today the port attracts the affluent yachting hoards in summer

but in early May the town was a quiet sleepy place with the harbour side

restaurants just beginning to prepare for summer influx of tourists. The

footpath sloped up past glorious banks of cowslips (see right) onto the cliff-tops

overlooking the sound with a side path branching down through a narrow squeeze

in high rocks, and we wound a slippery way among the rocks to the craggy

shore-line where eider ducks bobbed in the water with their characteristic 'oo-ing'

sound and terns flitted overhead making their piercing alarm calls. As we

rounded the island's western tip with its small lighthouse, the sun miraculously

broke through but with the SW wind still blowing briskly chill

(Photo 17 - Marstrand's rocky shoreline). We

followed the path over the shore-side rocks revelling in the glorious light

sparkling across the sea (see left), eventually completing the circuit back into the

southern end of Marstrand town by the sound to walk along the harbour front past

the wooden houses (Photo 18 - Wooden houses along Marstrand's waterfront).

We joined local people returning by the ferry across the sound, and walked back

to camp after such a glorious day's walk around Marstrand's rocky shore.

Island of Tjörn and Fishing village of

Klädesholmen: the following morning, we re-crossed the bridge and

causeways linking the islets of the archipelago, over the elegant bridge linking

to the larger Bohuslän island of Tjörn. Down at the island's SW tip we reached

the large fishing village of Klädesholmen spread across 2 interconnected

off-shore islets. Klädesholmen was also once a major herring fishing port with

30 fish-processing factories as described in the Herring Museum; but with the

disappearance of the herring, only a fraction of the former industry survives.

Former fishermen's cottages and sheds have now been converted to twee

residences, but the village is still a charming place. We spent a peacefully

contented afternoon wandering around the lanes and alleyways, with views between

white-painted cottages and red-painted former fishing sheds over small

anchorages out to the distant islands of the archipelago (Photo 19 - Fishing village of Klädesholmen on Tjörn island).

Across a small bridge connecting to Klädesholmen's outer islet, we continued

along Fiskhamnväg over a hillock down to the tiny harbour of Västra Hamn. Here

around the anchorage working fishing boats and smaller craft were moored (see

right). Not

only was this a peaceful and attractive setting among all the boats, looking

across the water to the white-painted cottages and church on the headland

opposite, of equal interest to us was the sheltered parking area by the

guest-harbour's toilets-showers: here was a perfect spot for tonight's camp. The

harbour-master was agreeable charging us 150kr as for the gästhamn, and we

settled in tucked behind a large rocky outcrop looking out over the boats in the

harbour and cottages across the bay; it was a truly beautiful spot to camp (Photo 20 - Camp at Klädesholmen's Västra Hamn fishing harbour). Island of Tjörn and Fishing village of

Klädesholmen: the following morning, we re-crossed the bridge and

causeways linking the islets of the archipelago, over the elegant bridge linking

to the larger Bohuslän island of Tjörn. Down at the island's SW tip we reached

the large fishing village of Klädesholmen spread across 2 interconnected

off-shore islets. Klädesholmen was also once a major herring fishing port with

30 fish-processing factories as described in the Herring Museum; but with the

disappearance of the herring, only a fraction of the former industry survives.

Former fishermen's cottages and sheds have now been converted to twee

residences, but the village is still a charming place. We spent a peacefully

contented afternoon wandering around the lanes and alleyways, with views between

white-painted cottages and red-painted former fishing sheds over small

anchorages out to the distant islands of the archipelago (Photo 19 - Fishing village of Klädesholmen on Tjörn island).

Across a small bridge connecting to Klädesholmen's outer islet, we continued

along Fiskhamnväg over a hillock down to the tiny harbour of Västra Hamn. Here

around the anchorage working fishing boats and smaller craft were moored (see

right). Not

only was this a peaceful and attractive setting among all the boats, looking

across the water to the white-painted cottages and church on the headland

opposite, of equal interest to us was the sheltered parking area by the

guest-harbour's toilets-showers: here was a perfect spot for tonight's camp. The

harbour-master was agreeable charging us 150kr as for the gästhamn, and we

settled in tucked behind a large rocky outcrop looking out over the boats in the

harbour and cottages across the bay; it was a truly beautiful spot to camp (Photo 20 - Camp at Klädesholmen's Västra Hamn fishing harbour).

The Bohuslän islands of Orust and Malö, and fishing port of Mollösund:

moving north, we crossed a further bridge across the narrow sound separating Tjörn

from Sweden's 3rd largest island, Orust. The central part of Orust was

surprisingly wooded with spectacular rocky outcrops and cleared farmland in the

areas between. At the end of a long inlet at the SW tip of the island, we

reached the small fishing port of Mollösund, clearly not a place to visit in

summer when the tiny village and harbour would be overwhelmed with

tourists. In mid-May the delightful place was deserted and we were able to park

right by the harbour-side where a few boats were moored (see left). Again we spent a happy

afternoon ambling around the harbour and fishing-processing factories, and the

cobbled lanes between the cottages and anchorages (Photo 21 - harbour-village

of Mollösund on Orust).

How many of these, we wondered were occupied by working residents rather than

holiday homes for city dwellers from Göteborg? We were told of a small campsite

on the further island of Malö, and expecting to cross by another bridge, we were

surprised when the road descended to the intervening sound ending at a barrier

and red traffic light for a small car-ferry. The ferry waited for the bus on the

far shore and we crossed without charge to Malö. After a night's camp, we

crossed the tiny island of Malö with its stunningly beautiful terrain of rocky

outcrops, passing farmsteads and tiny inlets with boats moored, for the

car-ferry linking back to the long mainland peninsula that extends out

into the Bohuslän archipelago to Fiskebäckskils (Photo 22 - Car ferry from Malö back to Bokenäs peninsula). The Bohuslän islands of Orust and Malö, and fishing port of Mollösund:

moving north, we crossed a further bridge across the narrow sound separating Tjörn

from Sweden's 3rd largest island, Orust. The central part of Orust was

surprisingly wooded with spectacular rocky outcrops and cleared farmland in the

areas between. At the end of a long inlet at the SW tip of the island, we

reached the small fishing port of Mollösund, clearly not a place to visit in

summer when the tiny village and harbour would be overwhelmed with

tourists. In mid-May the delightful place was deserted and we were able to park

right by the harbour-side where a few boats were moored (see left). Again we spent a happy

afternoon ambling around the harbour and fishing-processing factories, and the

cobbled lanes between the cottages and anchorages (Photo 21 - harbour-village

of Mollösund on Orust).

How many of these, we wondered were occupied by working residents rather than

holiday homes for city dwellers from Göteborg? We were told of a small campsite

on the further island of Malö, and expecting to cross by another bridge, we were

surprised when the road descended to the intervening sound ending at a barrier

and red traffic light for a small car-ferry. The ferry waited for the bus on the

far shore and we crossed without charge to Malö. After a night's camp, we

crossed the tiny island of Malö with its stunningly beautiful terrain of rocky

outcrops, passing farmsteads and tiny inlets with boats moored, for the

car-ferry linking back to the long mainland peninsula that extends out

into the Bohuslän archipelago to Fiskebäckskils (Photo 22 - Car ferry from Malö back to Bokenäs peninsula).

Back inland to Lake

Vänern and Halleberg-Hunneberg Plateau Nature

Reserve: the following morning's drive back inland would involve the

whole spectrum of roads, starting on the peaceful single-track rural lane across Malö,

minor roads, and finally the busy Route 44 motorway past Uddevalla to Vänersborg.

Our impression so far was that Swedish drivers were generally patient and

considerate, drove at speed when sensible but observed speed limits faithfully

without the aggressive overtaking, tail-gating and cutting in that now bedevils

driving in UK. Beyond Vänersborg, we crossed the wide River Göta which exits

from the inland-sea of Lake Vänern to flow as the Göta Canal down to Göteborg.

Leaving the main road, we took a winding minor road gaining height onto the

thickly wooded rocky Hunneberg Plateau. We knew of walks around the nature

reserve but needed a detailed map from the museum at the former royal hunting

lodge here. The elderly gent here charmed us with tales of Hunneberg's

history, culture and Back inland to Lake

Vänern and Halleberg-Hunneberg Plateau Nature

Reserve: the following morning's drive back inland would involve the

whole spectrum of roads, starting on the peaceful single-track rural lane across Malö,

minor roads, and finally the busy Route 44 motorway past Uddevalla to Vänersborg.

Our impression so far was that Swedish drivers were generally patient and

considerate, drove at speed when sensible but observed speed limits faithfully

without the aggressive overtaking, tail-gating and cutting in that now bedevils

driving in UK. Beyond Vänersborg, we crossed the wide River Göta which exits

from the inland-sea of Lake Vänern to flow as the Göta Canal down to Göteborg.

Leaving the main road, we took a winding minor road gaining height onto the

thickly wooded rocky Hunneberg Plateau. We knew of walks around the nature

reserve but needed a detailed map from the museum at the former royal hunting

lodge here. The elderly gent here charmed us with tales of Hunneberg's

history, culture and

geology, when all we wanted was a map and details of walks.

We did however learn that the 2 plateaux of Hunneberg/Halleberg had originally

been one plug of hard erosion-resistant rock created by the intrusion of magma

into the softer surrounding bedrock which had over time eroded leaving the

resistant plateau exposed with its sheer craggy cliff-edges rising 50m above the

surrounding plain and Lake Vänern. The plateau had been cleaved by tectonic

movement leaving a valley separating the 2 now distinct plateaux. Armed with our

map, we followed a lane up onto the northern wooded plateau of Halleberg to its

northern end. A path led to the plateau's eastern cliff-edge looking out across

over the inland sea of Lake Vänern which faded into the misty distance to the NE

with no trace of land (Photo 23 - Inland sea of Lake Vänern from Halleberg plateau).

We followed the nature reserve circular way-marked path around the cliffs of the

plateau's northern tip through the original oak and spruce forest, but it was

the delightful woodland flora that made this walk so memorable, particularly the

carpets of wood anemones (see left), occasional hepatica, wood sorrel, bilberry with its

bright green new leaf and tiny pink globular flowers, and patches of

distinctive lingonberry leaves, covering the woodland floor. At the northern

tip, another lookout point above the plateau's lofty cliff edge gave views out

across Lake Vänern (see right). This was a truly magical woodland walk especially in bright

afternoon sunshine. geology, when all we wanted was a map and details of walks.

We did however learn that the 2 plateaux of Hunneberg/Halleberg had originally

been one plug of hard erosion-resistant rock created by the intrusion of magma

into the softer surrounding bedrock which had over time eroded leaving the

resistant plateau exposed with its sheer craggy cliff-edges rising 50m above the

surrounding plain and Lake Vänern. The plateau had been cleaved by tectonic

movement leaving a valley separating the 2 now distinct plateaux. Armed with our

map, we followed a lane up onto the northern wooded plateau of Halleberg to its

northern end. A path led to the plateau's eastern cliff-edge looking out across

over the inland sea of Lake Vänern which faded into the misty distance to the NE

with no trace of land (Photo 23 - Inland sea of Lake Vänern from Halleberg plateau).

We followed the nature reserve circular way-marked path around the cliffs of the

plateau's northern tip through the original oak and spruce forest, but it was

the delightful woodland flora that made this walk so memorable, particularly the

carpets of wood anemones (see left), occasional hepatica, wood sorrel, bilberry with its

bright green new leaf and tiny pink globular flowers, and patches of

distinctive lingonberry leaves, covering the woodland floor. At the northern

tip, another lookout point above the plateau's lofty cliff edge gave views out

across Lake Vänern (see right). This was a truly magical woodland walk especially in bright

afternoon sunshine.

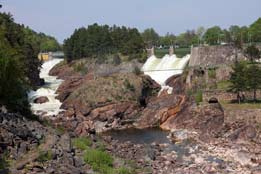

Trollhättan with its dam sluice-gate

waterfalls and excellent campsite: we joined the afternoon traffic on the

main road running alongside the Halleberg Plateau, with the 50m cliffs of its

western edge catching the afternoon sun, into the outskirts of Trollhättan, an

industrial town which developed on the banks of the Göta River/Canal. At the

town's campsite, we were welcomed with smilingly genuine hospitality; tired

after a long day, you could not have asked for a more kindly welcome: nothing

was too much trouble, showing an empathic understanding towards weary travellers

and giving us a street plan and directions for our visit to Trollhättan and the

best location for seeing the town's weekly spectacle, the opening of the sluice

gates on the Göta River dam which creates magnificent waterfalls. You are our

guests he said, a lesson which so many other campsite could usefully follow. For

a city campsite, 15 minutes' walk from the centre, the setting was delightfully

wooded, and the facilities spotlessly clean and modern. This really was a first

class and well-run campsite (see right). We later learnt that the Saab motor manufacturer

had had its main assembly plant here at Trollhättan but the firm had gone bust

and the plant, the town's largest employer had closed 2 years ago with the loss

of 4,000 jobs Trollhättan with its dam sluice-gate

waterfalls and excellent campsite: we joined the afternoon traffic on the

main road running alongside the Halleberg Plateau, with the 50m cliffs of its

western edge catching the afternoon sun, into the outskirts of Trollhättan, an

industrial town which developed on the banks of the Göta River/Canal. At the

town's campsite, we were welcomed with smilingly genuine hospitality; tired

after a long day, you could not have asked for a more kindly welcome: nothing

was too much trouble, showing an empathic understanding towards weary travellers

and giving us a street plan and directions for our visit to Trollhättan and the

best location for seeing the town's weekly spectacle, the opening of the sluice

gates on the Göta River dam which creates magnificent waterfalls. You are our

guests he said, a lesson which so many other campsite could usefully follow. For

a city campsite, 15 minutes' walk from the centre, the setting was delightfully

wooded, and the facilities spotlessly clean and modern. This really was a first

class and well-run campsite (see right). We later learnt that the Saab motor manufacturer

had had its main assembly plant here at Trollhättan but the firm had gone bust

and the plant, the town's largest employer had closed 2 years ago with the loss

of 4,000 jobs

and 3,000 further jobs in associates industries. What a blow this

must have been for a small community. and 3,000 further jobs in associates industries. What a blow this

must have been for a small community.

The following day, we set off to walk from the

campsite along the river/canal-side footpath into the town. The Volvo Aerospace

company has a manufacturing centre at Trollhättan and the town is also home to

Sweden's film industry, known colloquially as 'Trollywood'. Trollhättan's main

street of Storgatan is paved with Hollywood style pavement plaques, the town's

hall of fame naming some of the international film stars who have figured in movies

made in Trollywood. But our objective

today was to learn something of its industrial heritage with the important

navigable Göta Canal with its locks and the HEP generating plants along the Göta

River gorge.

The

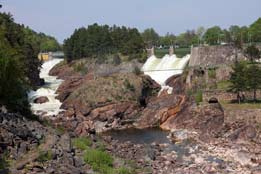

day's highlight was to be the opening of the HEP dam's sluice

gates creating 2 enormous waterfalls in the Göta gorge which during the

non-summer months only happens once a week at 3-00pm on Saturdays; our visit to Trollhättan

had been timed to coincide with this spectacle. The footpath ran through

parkland along an embankment separating the river's wide natural course from the

maintained canal still widely used by both commercial cargo shipping and pleasure

craft. At the centre of the town, the river's natural course and the modern,

artificially cut canal parted company. We continued ahead along the canal

embankment to reach an electrical distribution station close to one of the HEP

generating plants. Here we cut across the Oskarbron, a high lofty modern

bridge spanning the 150 feet deep craggy river gorge, now totally dry with the

river dammed for the nearby Hojums HEP generating plant. The

day's highlight was to be the opening of the HEP dam's sluice

gates creating 2 enormous waterfalls in the Göta gorge which during the

non-summer months only happens once a week at 3-00pm on Saturdays; our visit to Trollhättan

had been timed to coincide with this spectacle. The footpath ran through

parkland along an embankment separating the river's wide natural course from the

maintained canal still widely used by both commercial cargo shipping and pleasure

craft. At the centre of the town, the river's natural course and the modern,

artificially cut canal parted company. We continued ahead along the canal

embankment to reach an electrical distribution station close to one of the HEP

generating plants. Here we cut across the Oskarbron, a high lofty modern

bridge spanning the 150 feet deep craggy river gorge, now totally dry with the

river dammed for the nearby Hojums HEP generating plant.

From here, although we

could not see the lake retained by the 2 dams to create the head of water to

drive the generating plants turbines, we did have a perfect view 800m upstream

of the dam's sluice gates which would be opened to create the waterfalls spectacle filling the now dry gorge 150 feet below us. At 3-00pm a sudden

cascade of white water surged from the left-hand sluice gates snaking with

remarkable tardiness down into the rocky gorge and swelling out into a foaming

torrent. Equally suddenly, a similar torrent gushed from the other sluice

surging slowly down into the gorge bed to merge with the first to form one mass

of water advancing down into the dry bed. All of this seemed to happen in slow

motion taking a full 4 minutes from when the 2 sluices were opened to when the

merged nose of white water passed down the gorge's dry bed under the bridge

below us (Photos 24 & 25 - Start of Trollhättan waterfalls and merged torrent in full spate).

We stood in astonishment on the bridge gazing down at this remarkable spectacle. From here, although we

could not see the lake retained by the 2 dams to create the head of water to

drive the generating plants turbines, we did have a perfect view 800m upstream

of the dam's sluice gates which would be opened to create the waterfalls spectacle filling the now dry gorge 150 feet below us. At 3-00pm a sudden

cascade of white water surged from the left-hand sluice gates snaking with

remarkable tardiness down into the rocky gorge and swelling out into a foaming

torrent. Equally suddenly, a similar torrent gushed from the other sluice

surging slowly down into the gorge bed to merge with the first to form one mass

of water advancing down into the dry bed. All of this seemed to happen in slow

motion taking a full 4 minutes from when the 2 sluices were opened to when the

merged nose of white water passed down the gorge's dry bed under the bridge

below us (Photos 24 & 25 - Start of Trollhättan waterfalls and merged torrent in full spate).

We stood in astonishment on the bridge gazing down at this remarkable spectacle.

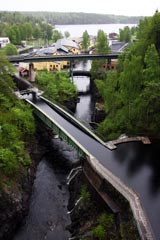

But

that was not the end of our appreciation of the industrial exploitation of the Göta

River; there was now the remarkable story of the Canal's development and the

problems facing its designers in engineering a navigable passage to bypass this

formidable obstacle of the Göta's 150 feet deep gorge. Earlier attempts to

achieve this had been foiled by technological inadequacies. But in 1844, enter

one Nils Ericson (1802~70), civil engineer extraordinary and Sweden's equivalent

of I K Brunel. He had been responsible for construction of the Saimaa Canal in

what was then Swedish Finland which we had travelled on last year to the now

Russian port of Vyborg. In order to bypass the Göta River's insurmountable

natural course, Ericson had to blast out an entirely new channel from the bed

rock parallel with but some distance from the river's natural course; there was

then the problem of lowering the new cut down the 150 feet drop in order for boats to

rejoin the river downstream of the gorge. Ericson achieved this with a long

series of locks (slussar) which we now walked to see (see right). The current

navigable channel was impressively wide and the on-going series of locks

continued for some distance from the top lock towards the lower river. A walk

back on the footpath alongside Ericson's canal cut further impressed us with the

creativity of this remarkable engineer who went on to develop the entire Swedish

national railway system. Before leaving we walked around to the lake retained

behind the dam; the footbridge spanning the dam gave a breath-taking impression

of the height loss in the river's gorge which Ericson's canal had to drop by

means of the flight of locks. We plodded wearily back to camp after such an

inspiring day of discovery, understanding more about Trollhättan's remarkable

industrial heritage and the twin exploitation of the Göta River both for canal

navigation and HEP generation. It is always the sign of a good campsite when you

are sorry to be leaving, and we had enjoyed an excellent stay here at

Trollhättan Camping. But

that was not the end of our appreciation of the industrial exploitation of the Göta

River; there was now the remarkable story of the Canal's development and the

problems facing its designers in engineering a navigable passage to bypass this

formidable obstacle of the Göta's 150 feet deep gorge. Earlier attempts to

achieve this had been foiled by technological inadequacies. But in 1844, enter

one Nils Ericson (1802~70), civil engineer extraordinary and Sweden's equivalent

of I K Brunel. He had been responsible for construction of the Saimaa Canal in

what was then Swedish Finland which we had travelled on last year to the now

Russian port of Vyborg. In order to bypass the Göta River's insurmountable

natural course, Ericson had to blast out an entirely new channel from the bed

rock parallel with but some distance from the river's natural course; there was

then the problem of lowering the new cut down the 150 feet drop in order for boats to

rejoin the river downstream of the gorge. Ericson achieved this with a long

series of locks (slussar) which we now walked to see (see right). The current

navigable channel was impressively wide and the on-going series of locks

continued for some distance from the top lock towards the lower river. A walk

back on the footpath alongside Ericson's canal cut further impressed us with the

creativity of this remarkable engineer who went on to develop the entire Swedish

national railway system. Before leaving we walked around to the lake retained

behind the dam; the footbridge spanning the dam gave a breath-taking impression

of the height loss in the river's gorge which Ericson's canal had to drop by

means of the flight of locks. We plodded wearily back to camp after such an

inspiring day of discovery, understanding more about Trollhättan's remarkable

industrial heritage and the twin exploitation of the Göta River both for canal

navigation and HEP generation. It is always the sign of a good campsite when you

are sorry to be leaving, and we had enjoyed an excellent stay here at

Trollhättan Camping.

North towards the Norwegian border and the

Tanum-Vitlycke Bronze Age rock engravings: the E6 motorway northwards

passing through increasingly spectacular terrain of wooded hills, with

occasional glimpses of coastal fjords and sensational viaducts spanning broad

valleys. We turned off North towards the Norwegian border and the

Tanum-Vitlycke Bronze Age rock engravings: the E6 motorway northwards

passing through increasingly spectacular terrain of wooded hills, with

occasional glimpses of coastal fjords and sensational viaducts spanning broad

valleys. We turned off

onto

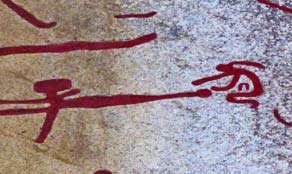

a minor road leading to the Tanum-Vitlycke Museum which we hoped would provide interpretation of the prehistoric rock engravings around Tanum

to supplement the Rock Carvings Tour booklet bought at the North Bohusläs

Museum in Uddevalla. The

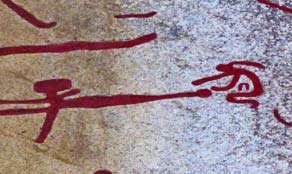

panels of rock art around North Bohuslän dating from the mid-late Bronze Age

around 1500~500 BC were chiselled onto flat panels of bed-rock granite using

flint tools. At that time, sea levels were higher than today so that most of the

panels were along fjord shore-lines. Unlike the Neolithic nomadic hunter-gathers

who had created the ritual engravings at Alta in North Norway seen by us last

year, the Tanum rock art was created by a more settled agricultural culture who

supplemented their pastoral existence keeping sheep, pigs and cattle and working

the land to grow barley and rye, with hunting in the surrounding forests. Bronze

was bartered from Europe for skins and local produce, and smelted for weapons

and ceremonial ornaments. The carved rock figures supported by archaeological

finds show a continuity of occupation and land use for over 1000 years. There

are 4 areas of rock engravings, and the panel at Tanum-Vitlycke was clearly

visible on the opposite hillside. As at Alta, the figures engraved on the flat

granite panels had controversially been coloured in with red paint to make them

more visible to modern day visitors (Photo 26 - Tanum Bronze Age rock engravings from 1500~500 BC).

Although difficult to interpret, the art-work of some 300 human and animal

figures, boats and other symbols is thought to represent religious ceremonial

ritual, fertility rites and representation of the passage from life to death.

The

best-known figures are a male-female pairing known as 'The Lovers' engaged

in an obvious human act but with a warrior figure holding an axe above the onto

a minor road leading to the Tanum-Vitlycke Museum which we hoped would provide interpretation of the prehistoric rock engravings around Tanum

to supplement the Rock Carvings Tour booklet bought at the North Bohusläs

Museum in Uddevalla. The

panels of rock art around North Bohuslän dating from the mid-late Bronze Age

around 1500~500 BC were chiselled onto flat panels of bed-rock granite using

flint tools. At that time, sea levels were higher than today so that most of the

panels were along fjord shore-lines. Unlike the Neolithic nomadic hunter-gathers

who had created the ritual engravings at Alta in North Norway seen by us last

year, the Tanum rock art was created by a more settled agricultural culture who

supplemented their pastoral existence keeping sheep, pigs and cattle and working

the land to grow barley and rye, with hunting in the surrounding forests. Bronze

was bartered from Europe for skins and local produce, and smelted for weapons

and ceremonial ornaments. The carved rock figures supported by archaeological

finds show a continuity of occupation and land use for over 1000 years. There

are 4 areas of rock engravings, and the panel at Tanum-Vitlycke was clearly

visible on the opposite hillside. As at Alta, the figures engraved on the flat

granite panels had controversially been coloured in with red paint to make them

more visible to modern day visitors (Photo 26 - Tanum Bronze Age rock engravings from 1500~500 BC).

Although difficult to interpret, the art-work of some 300 human and animal

figures, boats and other symbols is thought to represent religious ceremonial

ritual, fertility rites and representation of the passage from life to death.

The

best-known figures are a male-female pairing known as 'The Lovers' engaged

in an obvious human act but with a warrior figure holding an axe above the

bonding couple's heads (see right). Another

figure portrayed a warrior wearing a horned helmet and travelling in a 2-wheeled

horse-drawn chariot;

the

nearby snake-like emblem is thought to represent a

lightning bolt and the charioteer perhaps an pre-cursor bonding couple's heads (see right). Another

figure portrayed a warrior wearing a horned helmet and travelling in a 2-wheeled

horse-drawn chariot;

the

nearby snake-like emblem is thought to represent a

lightning bolt and the charioteer perhaps an pre-cursor of the Nordic god of

thunder Thor (see left). There were also a number of boat figures thought

ritually to represent the passage from this life to the kingdom of the dead. In the centre of the panel was a unique depiction of a female figure

(distinguishable by her plaited hair) mourning a dead male (see left)

of the Nordic god of

thunder Thor (see left). There were also a number of boat figures thought

ritually to represent the passage from this life to the kingdom of the dead. In the centre of the panel was a unique depiction of a female figure

(distinguishable by her plaited hair) mourning a dead male (see left)

We drove around to the other 3 sites in the nearby

pine woods to examine more of the engravings. One panel showed a huge 2.3m high figure of a god

brandishing his spear. Some of the engravings had been spared the colouring to

reveal their original state, one of which dating from the early Iron Age showed

horsemen bearing spear and shield (see right). Others showed processions of

dancing figures and bulls with superimposed figure reminiscent of the Minoan

Cretan bull-leapers at Knossos (see left below); was this a common Bronze Age Indo-European

ritual theme? There were regular depictions of hunting scenes with warriors

pursuing animals with spears and bows (Photo 27 - Ritual hunting scene) and

axe-men with hunting dogs. We spent the whole afternoon photographing these

mysterious yet intensely human pieces of prehistoric artwork. We had envisaged

staying

that night at the small Tanums Camping, but found it closed. The only

alternative was one of the over-crowded and uninviting holiday-camps down at the

coast, the least unappealing of which, Saltviks Camping, enjoys the

distinction of being one of the most memorably disgusting campsites we have ever

had the misfortune to use, as well as over-pricey; the inhospitable

owner could not even be bothered to open the office, nor did we feel inclined to

part with kroner for such an unpleasant stay, and the following morning

thankfully hastened away to continue our journey northward. staying

that night at the small Tanums Camping, but found it closed. The only

alternative was one of the over-crowded and uninviting holiday-camps down at the

coast, the least unappealing of which, Saltviks Camping, enjoys the

distinction of being one of the most memorably disgusting campsites we have ever

had the misfortune to use, as well as over-pricey; the inhospitable

owner could not even be bothered to open the office, nor did we feel inclined to

part with kroner for such an unpleasant stay, and the following morning

thankfully hastened away to continue our journey northward.

The Blomsholm 'Stone Ship' Iron Age burial mound: as we drew closer to the

Norwegian border, upgrading of the road which led eventually to Oslo meant a

diversion with traffic queuing to rejoin the motorway; driving standards of the

predominantly Norwegian traffic was far more aggressive and less tolerant than

Swedish drivers. Thankful to be leaving the motorway, we turned off on a quiet

lane to Blomholmens Säteris (manor house), the estate where the Blomsholm

Stenskeppet (Stone Ship) Iron Age burial mound is located. As we approached, the

standing stones forming the sip's outline could be seen topping a low hillock

across the fields. 49 standing stones arranged in the shape of a long boat, 41m

long and 9m wide with bow and stern stones 3m high (Photo 28 - Strömstad 'Stone Ship' Iron Age burial mound). Although it is the largest

such boat-grave in Sweden, little is known of its history. It is thought to date

from the late Iron Age, between 500~1000 AD, when sea levels were higher than

now and the lower ground near the grave would have been the shore-line of an

inlet from the sea. Boats clearly were of ritual importance to prehistoric

northern peoples as the rock art had shown, symbolising the passage from life to

death. Although the hillock forming tumulus beneath the stone-circle has never

been excavated, it is assumed that it marks a grave and the size of the monument

indicates an important chieftain. We had seen such smaller stone-ships in

Northern Jutland which once would have been buried under soil; this one however

was never covered and was designed to be visible from the shallow bay it

overlooked. Clearly this was an impressive monument even 1,500 years after it

received its VIP burial. predominantly Norwegian traffic was far more aggressive and less tolerant than

Swedish drivers. Thankful to be leaving the motorway, we turned off on a quiet

lane to Blomholmens Säteris (manor house), the estate where the Blomsholm

Stenskeppet (Stone Ship) Iron Age burial mound is located. As we approached, the

standing stones forming the sip's outline could be seen topping a low hillock

across the fields. 49 standing stones arranged in the shape of a long boat, 41m

long and 9m wide with bow and stern stones 3m high (Photo 28 - Strömstad 'Stone Ship' Iron Age burial mound). Although it is the largest

such boat-grave in Sweden, little is known of its history. It is thought to date

from the late Iron Age, between 500~1000 AD, when sea levels were higher than

now and the lower ground near the grave would have been the shore-line of an

inlet from the sea. Boats clearly were of ritual importance to prehistoric

northern peoples as the rock art had shown, symbolising the passage from life to

death. Although the hillock forming tumulus beneath the stone-circle has never

been excavated, it is assumed that it marks a grave and the size of the monument

indicates an important chieftain. We had seen such smaller stone-ships in

Northern Jutland which once would have been buried under soil; this one however

was never covered and was designed to be visible from the shallow bay it

overlooked. Clearly this was an impressive monument even 1,500 years after it

received its VIP burial.

Strömstad Camping: we returned along the lane to negotiate the traffic queue

at the motorway junction, and on the outskirts of Strömstad pulled in at what we

thought was a shopping centre. But the predominance of Norwegian cars should

have alerted us that this was no conventional out-of-town supermarket. This was

hyper-greed at its very worst - cross-border trade where Norwegians swarmed

frantically in

their 1000s for cheap booze and consumer goods. Extricating ourselves from this

materialistic madness into Strömstad, we managed to park in the main street to

do our shopping at perfectly normal Co-op. Strömstad was a pleasant town: what had once been

a small fishing port had developed into a late 19th century spa town with the

main spa centre still dominating the marina. Ferries ran from here to the

off-shore Kosterhavet Islands, since 2009 protected as Sweden's first marine

national park. We were greeted at the local campsite with smiling hospitality

and a good value price of 210kr with no hidden extras and free wi-fi internet;

it was one of those campsites that recognises the sensible formula for success

of welcoming its guests as a hotel would. But the impressively distinctive

feature was the ingenious way it had managed somehow to implant flat and

extensive camping areas across the huge rocky outcrops of the broad headland on

which it was sited. We tucked ourselves into a secluded and sheltered corner

under a rocky outcrop overlooking the steep-sided valley of a fjord-inlet. This

was a magnificently unique spot in which to enjoy a day in camp (Photo 29 - Strömstad Camping on headland overlooking fjord-inlet). Strömstad Camping: we returned along the lane to negotiate the traffic queue

at the motorway junction, and on the outskirts of Strömstad pulled in at what we

thought was a shopping centre. But the predominance of Norwegian cars should

have alerted us that this was no conventional out-of-town supermarket. This was

hyper-greed at its very worst - cross-border trade where Norwegians swarmed

frantically in

their 1000s for cheap booze and consumer goods. Extricating ourselves from this

materialistic madness into Strömstad, we managed to park in the main street to

do our shopping at perfectly normal Co-op. Strömstad was a pleasant town: what had once been

a small fishing port had developed into a late 19th century spa town with the

main spa centre still dominating the marina. Ferries ran from here to the

off-shore Kosterhavet Islands, since 2009 protected as Sweden's first marine

national park. We were greeted at the local campsite with smiling hospitality

and a good value price of 210kr with no hidden extras and free wi-fi internet;

it was one of those campsites that recognises the sensible formula for success

of welcoming its guests as a hotel would. But the impressively distinctive

feature was the ingenious way it had managed somehow to implant flat and

extensive camping areas across the huge rocky outcrops of the broad headland on

which it was sited. We tucked ourselves into a secluded and sheltered corner

under a rocky outcrop overlooking the steep-sided valley of a fjord-inlet. This

was a magnificently unique spot in which to enjoy a day in camp (Photo 29 - Strömstad Camping on headland overlooking fjord-inlet).

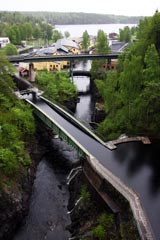

Inland to Dalsland and the Håverud Aqueduct: glad to be getting

away from rowdy Norwegians in their ludicrous mega-buses (this was not camping

but sordid materialism-on-wheels), today we should finally leave the Bohuslän

Coast and turn inland through a corner of southern Norway on minor roads through